Mammalian ovaries undergo considerable remodeling during the lifetime of the organism, leading to the supposition that somatic stem cells account for or contribute to this cyclic regeneration. While much of ovarian stem cell research has been focused on germ cells, recent interest in normal somatic stem cells has been driven by their possible links to ovarian cancer stem cells. While evidence for stem cell biology with regards to granulosa cells is scant, recent work has isolated potential somatic stem cells for the theca and ovarian surface epithelium. Additionally, evidence for potential cancer initiating cells for ovarian epithelial carcinomas continues to mount.

1. Introduction

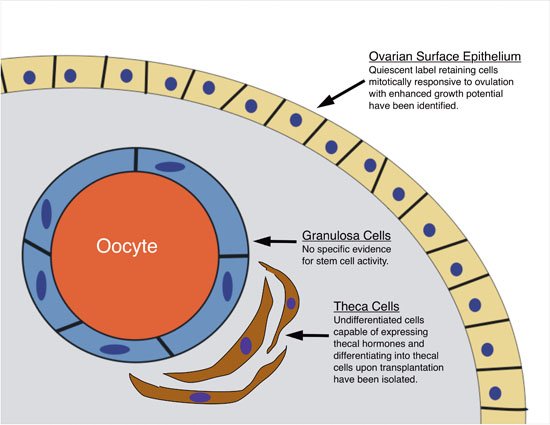

Reproductive organs undergo considerable remodeling during the lifetime of the mammalian organism, leading to the supposition that somatic stem cells account for or contribute to this cyclic regeneration. While much of ovarian stem cell research has been focused on germ cells, recent interest in normal somatic stem cells has been driven by their possible links to ovarian cancer stem cells. Given that the ovarian surface epithelium is the postulated source for 90% of human ovarian cancers (Gondos, (1975); Herbst, (1994); Auersperg et al., (1998)), understanding presumptive stem/progenitor function in this less well understood component of the ovary may reveal mechanisms of tumor progression with resultant important clinical implications. The current status of our understanding of stem cell biology in the somatic components of the ovary is schematized in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Schematic summary of current evidence for ovarian somatic stem cells. Of the three primary functional somatic cell types of the ovary, the ovarian surface epithelium and the theca cells currently have evidence supporting stem/progenitor cell biology (briefly stated in figure) whereas there is no specific evidence for stem cell activity associated with granulosa cells.

2. Ovarian development

An understanding of the salient features of normal ovarian development is necessary before delving into stem cell functions of its somatic compartments and begins with the formation, migration, and organogenesis of the germ cells (see Loffler and Koopman, (2002) and Oktem and Oktay, (2008) for comprehensive reviews).

2.1. Germ cells

Primordial germ cells (PGCs) form at E6.5 in the proximal epiblast where as few as six Blimp-1 expressing cells are detected (Ohinata et al., (2005)). Blimp-1 appears to initiate lineage specificity by repressing Hox and other somatic genes while extra-embryonic ectoderm BMP 2, 4, and 8b signaling (Molyneaux and Wylie, (2004); Lawson et al., (1999); Ying et al., (2000)) expands this population which expresses tissue-specific alkaline phosphatase and Stella (Saitou et al., (2002)) at embryonic day 7.2 (E7.2) in the mouse (Ginsburg et al., (1990)) and as early as week 3 in the endoderm of the yolk sac wall of the human (Hacker and Moore, 1992). PGC migration to the mesonephros occurs between E8-E12 in the mouse (Loffler and Koopman, (2002)) and week 8 of gestation in the human (Hacker and Moore, 1992). Mouse primordial germ cells undergo proliferation and imprint erasure as they traverse from the proximal primitive streak at the base of the allantois to the hindgut endoderm (E8.5–9.5) and then to the genital ridges. Progression of the PGCs to the developing urogenital ridges appears to involve largely uncharacterized chemotactic signals (De Felici et al., (2005); Molyneaux et al., (2003); Godin et al., (1990)), integrins (Anderson et al., (1999)), and C-kit signaling (Buehr et al., (1993)). As they migrate, PGCs proliferate 170-fold by mitotic division (Tam and Snow, (1981)) and lose imprinting imposed by DNA methylation (E10.5–12.5; Hajkova et al., (2002); Lee et al., (2002); Reik and Walter, (2001)) and complex chromatin modification by methylation or acetylation of histones on lysine and arginine residues (Hajkova et al., (2008); Seki et al., (2007); Seki et al., (2005); Kimmins and Sassone-Corsi, (2005)). This erasure is presumably necessary to reset epigenetic memory in germ cells and its complex regulation remains a continuing challenge for somatic nuclear transfer. The transmembrane protein Fragilis induces the germ cell gene Stella which represses the developmental homeobox genes, while Oct4, Sox2, and Nanog, preserve the pleuripotency of the PGCs (Saitou et al., (2002)). The PGCs lose their migratory phenotype at E12.5 (Ginsburg et al., (1990)) and at E13.5 female germ cells undergo meiosis in an anterior to posterior wave which denotes ovarian differentiation to become oogonia, a process mediated by Stra8 which is stimulated by retinoic acid. In contrast to the embryonic ovary, the embryonic testes expresses CYP26b1 which degrades retinoic acid so Stra8 is not expressed (Bowles et al., (2006); Koubova et al., (2006)).

Normal migration and colonization of the PGCs are necessary for further ovarian development, as ovarian dysgenesis with degeneration of ovarian somatic cells occurs in germ cell deficient mice (Merchant-Larios and Centeno, (1981); Behringer et al., (1990); Hashimoto et al., (1990)). Death of germ cells occurs when E12.5 ovaries are placed ectopically beneath the renal capsule, an event followed by formation of testicular tubules, again indicating the important role of the germ cells in ovarian development (Taketo et al., (1993)). Furthermore, there is evidence to suggest developmental germ cell tumors may result from incomplete migration of the PGCs to the developing ovary (Göbel et al., 2000; Schneider et al., (2001)).

2.2. Ovarian somatic tissue and ovarian surface epithelium

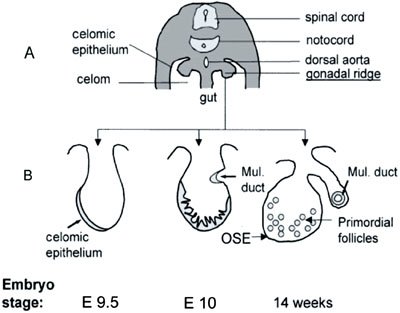

Figure 2 gives a schematic overview of ovarian somatic development. The development of the somatic gonad begins on E10 in the mouse (4 weeks gestation in the human) as a thickening of the coelomic epithelium on the ventro-medial side of the mesoderm (Swain and Lovell-Badge, (1999)). The indifferent gonad is essentially a mass of blastema (the primordial mesenchymal cell mass) surrounded by the coelomic-epithelium derived surface epithelium. This mesenchymal cell mass contains elements which are destined to become the supportive (granulosa), steroidogenic (theca and granulosa), or structural (stroma) cells of the ovary. After the primordial germ cells arrive in the developing gonad (∼E12–13.5), an arrangement of loose cords called the ovigerous cords begins to form around clusters of germ cells (Odor and Blandau, (1969); Konishi et al., (1986)). Developing somatic cells (presumed pre-granulosa cells) then separate the germ cell clusters into individual oocytes surrounded by a monolayer of granulosa cells, forming the primordial follicle (Pepling and Spralding, (1998); Merchant-Larios and Chimal-Monroy, (1989)). While the embryonic origins of the granulosa cells are still a matter of debate, there is evidence suggesting that the ovarian surface epithelium is at least a partial source of granulosa cells (Sawyer et al., (2002)).

Figure 2. Schematic representation of ovarian embryonic development. (A) Cross-section through the dorsal part of a 13-mm human embryo. (B) Sequential changes in the gonadal ridge, which is covered by modified coelomic epithelium (shaded). The epithelium proliferates and forms cords that penetrate into the ovarian cortex and give rise to the granulosa cells of the primordial follicles. The follicles become separated from the overlying ovarian surface epithelium (OSE) by stroma. The Mullerian ducts (Mul. Duct) develop as invaginations of the coelomic epithelium dorsolaterally from the gonadal ridges. (Adapted with permission from Auersperg, N., Wong, A.S., Choi, K.C., Kang, S.K., Leung, P.C. ((Auersperg et al., 2001)). Ovarian surface epithelium: biology, endocrinology, and pathology. Endocr Rev 22, 255–288. Figure 1. Copyright 2001, The Endocrine Society).

2.3. Genetic regulation of ovarian development

Compared to the genetic regulation of testicular development, the genes responsible for ovarian development are relatively unknown and it was once thought the ovaries developed passively as a result of the absence of testicular determining genes. Only a handful of genes required for the formation of the ovary have been identified and studied, almost exclusively in the mouse. Of these, Wnt-4 is the gene most clearly associated with ovarian development, with homozygous mutant males exhibiting normal testicular development while their female counterparts are virilized with absence of the Müllerian duct and morphologically masculinzed gonads with subsequent degeneration of meiotic-stage oocytes (Vainio et al., (1999)). Follistatin is a downstream component of Wnt-4 signaling which has also been associated with regulating normal ovarian organogenesis (Yao et al., (2004)). Recent data has shown that Wnt-4 activation is regulated by Respondin-1 mediation of the canonical β-catenin pathway and that β-catenin stabilization in the XY gonad is sufficient to cause male-to-female sex reversal (Chassot et al., (2008); Maatouk et al., (2008)). Additionally, a member of the forkhead transcription factors, Foxl2, has been identified as a gene that appears to repress the male genetic program and insure normal granulosa cell development around growing oocytes, allowing for normal ovarian development (Ottolenghi et al., (2005); Schmidt et al., (2004); Uda et al., (2004)). While work continues on the genetic regulation of ovarian development, it is interesting to note that prenatal ovarian development occurs independent of steroid hormone action (Couse et al., (1999)).

3. Granulosa and theca cells

The granulosa and theca cells of the ovary serve to support the germ cells within the developing follicle. Initially indistinguishable from the ovarian stroma, theca cells surround the developing follicle, form the two layers known as the theca externa and interna, and produce the androgens which are ultimately converted to estradiol by the granulosa cells. While converting theca-produced androgens into estradiol via aromatase, the granulosa cells form the multilayered cumulus oophorus and later the Graafian or pre-ovulatory follicle which surrounds the germ cells. After ovulation, both the granulosa and theca cells contribute to the corpus luteum which is responsible for producing the estrogen and progesterone necessary to support a developing pregnancy. While the complex biology of these cells suggests an obvious somatic stem cell-mediated process, substantive evidence to this end is lacking for the granulosa cells but is just recently being elucidated for the theca cells.

3.1. Granulosa cells

The origin of the pre-granulosa cells (the flattened somatic cells of the primordial follicle surrounding the oocyte) is not known but evidence supports three proposed sources: the developing ovarian blastema (Pinkerton et al., (1961)), the mesonephric cells of the rete ovarii (Byskov and Lintern-Moore, (1973)), and the developing ovarian surface epithelium (Gondos, (1975); Sawyer et al., (2002)). Until recently, most would have agreed that the cells that give rise to the granulosa cells (and their derived structures) during folliculogenesis have already segregated with each primordial follicle, and separate each germ cell from the surrounding ovarian stroma by a basal lamina where they lie dormant prior to follicular recruitment. While Bukovsky ((1995); (Bukovsky et al., 2004); (Bukovsky et al., 2008)) suggests that the tunica albuginea immediately underlying the ovarian surface epithelium gives rise to both post-natal oocytes and their associated pre-granulosa cells (Bukovsky et al., (2004)), the existence of germline stem cells and the possibility of post-natal oogenesis and their further development remains to be determined definitively (Johnson et al., (2005); Eggan et al., (2006), see Tilly et al., (2008) for a comprehensive review).

While granulosa cell growth and differentiation during folliculogenesis is a complex and interesting interplay of paracrine and endocrine factors, definitive evidence that the development of the granulosa-derived structures of the follicle is a stem cell-mediated process has yet to be produced. It could be argued that given the complex changes that occur during folliculogenesis, the pre-granulosa cells residing in the primordial follicle should be labeled fate-determined progenitor cells capable of forming the various structures of the developing follicle. However, there has been a lack of evidence so far to support the presence of asymmetric division, pluri- or multi- potency, or indefinite self-renewal in granulosa cells that characterizes stem cell biology.

3.2. Theca cells

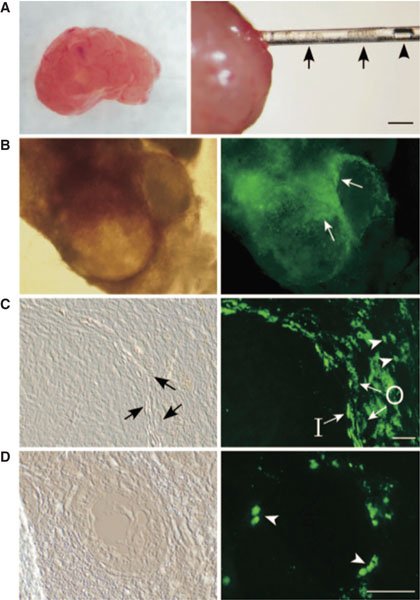

While the presence of probable theca cell precursors in the ovarian stroma and interstitium was proposed by Hirshfield in (1991), identification and isolation of these cells has proven elusive. Recent work by Honda and his colleagues (Honda et al., (2007)) led to isolation of ‘putative thecal stem cells’ after enzymatic and mechanical dissociation of newborn mice ovaries and growth of the resulting cell suspension in serum-free germline stem cell (GS) media. Non-adherent anchorage independent spheres exhibited the morphology of ovarian interstitial somatic cells and expressed gene profiles suggestive of theca cells, not germ or granulosa cells. By supplementing the media with serum, luteinizing hormone, insulin-like growth factor-1, stem cell factor, and granulosa cell-conditioned media in a stepwise manner, they were able to induce subcultures of these cells to differentiate into lipid producing, androgen secreting cells which morphologically resembled theca cells. Furthermore, transplantation of these cells isolated from whole-body green fluorescence protein-expressing transgenic mice into the ovaries of wild-type recipients showed scattered interstitial GFP with aggregation of GFP cells immediately adjacent to developing follicles and subsequent GFP expression in both theca interna and externa during folliculogenesis (see Figure 3). While there are still questions to be answered such as the exact location of these thecal precursors in vivo, the cell surface marker profile of these cells, and the niche in which these cells reside, the ability to isolate and characterize these cells represents a significant step towards understanding follicular development.

Figure 3. Intraovarian transplantation of the thecal stem cells. (A) A host ovary from a mature mouse (left). Thecal stem cell colonies (arrows in right) were transplanted into the ovary by a glass pipette. An air bubble placed for controllable transfer (arrowhead). (Scale bar: 2 mm) (B) Donor thecal cells (EGFP-positive) surrounding two large follicles were clearly visible by fluorescence microscopy (arrows). (C) Frozen section of a large follicular area. The donor thecal stem cells differentiated into large cells and were located in both the inner (I) and outer (O) thecal layers. They were also present in the interstitial area of small cells (arrowheads). (Scale bar: 50 mm) (D) Frozen section of a small primary follicle. A few small, probably less differentiated, theca cells were present around the follicle (arrowheads). (Scale bar: 50 mm) (B-D right) Corresponding fields observed by fluorescent microscopy are shown. (Adapted with permission from Honda, A., Hirose, M., Hara, K., Matoba, S., Inoue, K., Miki, H., Hiura, H., Kanatsu-Shinohara, M., Kanai, Y., Kono, T. et al. ((Honda et al., 2007)). Isolation, characterization, and in vitro and in vivo differentiation of putative thecal stem cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 104, 12389–12394. Figure 5. Copyright 2007 National Academy of Sciences, U.S.A).

4. Granulosa cell tumors and thecomas

Adult granulosa cell tumors (GCT), the most common ovarian stromal tumor, account for approximately 2–5% of all ovarian cancers. Juvenile GCTs are 20 to 50 times more rare (Schumer and Cannistra, (2003); Colombo et al., (2007)). Unlike the epithelial ovarian cancers, sex-cord stromal ovarian tumors (including granulosa cell tumors and thecomas) do not seem to have a demonstrable hereditary component. In addition, reports of oncogene involvement are inconclusive (Semczuk et al., (2004); Shen et al., (1996); Enomoto et al., (1991)), though there is data to suggest dysregulation of the canonical Wnt/β-catenin pathway may play a role in the development of granulosa cell tumors (Boerboom et al., (2005)). Additionally, an imbalance in chromosomes 4, 9, and 12 have been reported repeatedly in thecomas, suggesting that genes in these regions may contribute to the development of these tumors (Streblow et al., (2007); Liang et al., (2001); Shashi et al., (1994)). Evidence for stem cells in these tumors is, however, circumspect at best. Based solely upon morphological and histological factors, reports have implicated putative somatic stem cell involvement in certain ovarian stromal tumor subtypes, such as sertoli-leydig cell tumors in women; however, evidence that would definitively confirm these observations is currently lacking.

5. Ovarian surface epithelium and related malignancies

5.1. Ovarian surface epithelium

The simple squamous-to-cuboid single-layered epithelial cell structure of the normal human ovarian surface epithelium (OSE) belies its complex biology. Several studies have shown that rather than being a passive structure during ovulation, the OSE plays an active role in both follicular rupture and subsequent ovarian remodeling. The fact that OSE can transition back and forth between epithelial and mesenchymal phenotypes has been well-established (Kruk and Auersperg, (1992); Auersperg et al., (1999); Salamanca et al., 2004; reviewed in Ahmed et al., (2007)) and this epithelial-mesenchymal transition is believed to be part of the normal process of post-ovulatory ovarian remodeling. Additionally, the OSE has been shown to contribute to repairing the ovarian stroma after ovulation by producing and remodeling components of the extracellular matrix (Kruk and Auersperg, (1992); Kruk and Auersperg, (1994); Auersperg et al., (2001); Salamanca et al., 2004).

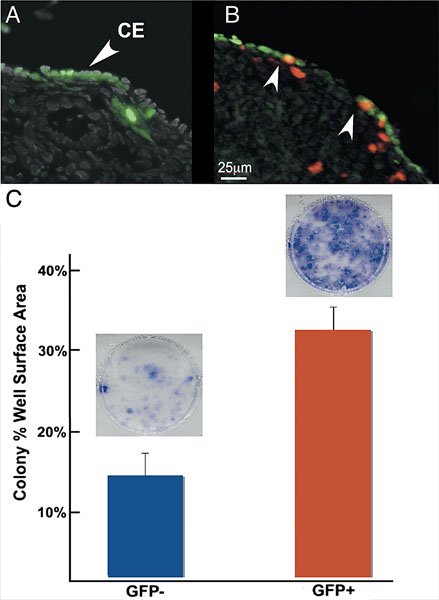

Given its ability to differentiate between two cell types and its role in the cyclical disruption and repair that occurs with ovulation, OSE biology seems an intuitive candidate to study in order to understand stem cell mediated processes. We studied the normal OSE as a somatic stem cell source given that repeated ovulation is thought to predispose the OSE, the postulated origin of 90% of ovarian carcinomas, to malignant transformation (Mahdavi et al., (2006)). Szotek and colleagues have recently identified a putative somatic stem/progenitor cell in the ovarian surface epithelium (Szotek et al., (2008)). A transgenic mouse model of doxycycline inducible green fluorescence protein tagged histones (Tet-on-H2B-GFP) was used; after an initial prolonged pulse, GFP expression or fluorescence can be followed or chased (Tumbar et al., (2004); Brennand et al., (2007)). After a chase period of several months, we identified slowly-cycling or quiescent cells in the OSE by retention of label (see Figure 4A), while mitotically active cells which should, by diluting their GFP label with each division, be unlabelled. Using quiescence and label retention as evidence for asymmetric division of the OSE, we then characterized the OSE LRCs by expression of the epithelial markers (cytokeratin-8 and E-cadherin) and the mesenchymal marker, Vimentin, and enrichment in the cytoprotective ABC transporter-associated Hoescht dye-excluding side population (SP), which has been associated with stem/progenitor cells in a variety of tissues and malignancies (Goodell et al., (1996); Jonker et al., (2005); Szotek et al., (2006); Ono et al., (2007); Rossi et al., (2008)). When examined for mitotic activity before and after ovulation by iodo-deoxy-uracil (IdU) incorporation, these GFP LRCs were induced to proliferate after ovulation, indicating responsiveness to the estrous cycle (see Figure 4B). Finally, these LRCs showed increased growth potential compared to their non-GFP counterparts in in vitro colony formation assays (see Figure 4C). Furthermore, we observed that these LRCs were consistently found adjacent to CD31+ vascular endothelial cells (Movie; Szotek, unpublished observations). These assays and characteristics collectively point to these cells as the putative somatic stem/progenitor cell of the OSE (Szotek et al., (2008)).

Figure 4. Identification and functional characterization of label retaining cells in the ovarian surface epithelium. (A) Three month chase of H2B-GFP ovaries demonstrate label retaining cells (LRCs) in the coelomic epithelium (CE) of the ovary. (B) CE LRCs were observed to colocalize with IdU (arrowheads) on either sides of the re-epithelializing ovulation wound, indicating mitotic activity in this area. (C) H2B-GFP 4 month chase CE cells sorted for GFP showed increased colony formation by well surface area percentage compared to non-GFP cells (35% versus 14%, P<0.05, n = 3). Representative Giemsa-stained non-GFP and GFP wells (C, inset) shown above their respective graph bars. (Adapted with permission from Szotek, P.P, Chang, H.L., Brennand, K., Fujino, A., Pieretti-Vanmarcke, R., Lo Ceslo, C., Dombkowski, D., Preffer, F., Cohen, K.S., Teixeira, J., Donahoe, P.K. ((Szotek et al., 2008)). Normal ovarian surface epithelial label-retaining cells exhibit stem/progenitor cell characteristics. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 105, 12469–12473. Figures 1C, 3B, and 4D. Copyright 2008 National Academy of Sciences, U.S.A)

Another property that has been attributed to the OSE is the ability post-natally to contribute new follicles to the pool of primordial follicles. Studies published by Bukovsky and colleagues present data in which they contend the tunica albuginea of the post-natal ovary immediately underlying the OSE is capable of producing new primordial follicles ((Bukovsky et al., 1995); (Bukovsky et al., 2004); (Bukovsky et al., 2008)). Recent studies have reported the isolation of cells from OSE of postmenopausal women and women with premature ovarian failure which express developmental embryonic markers including Oct-4, VASA, Nanog, c-Kit and Sox-2 (Virant-Klun et al., (Virant-Klun, I. Rozman, P. Cvjeticanin, B. Vrtacnik, . Bokal, E. Novakovic, S. Ruelicke, T. (2008a). Parthenogenetic embryo-like structures in the human ovarian surface epithelium cell culture in postmenopausal women with no naturally present follicles and oocytes. Stem Cells Dev 7 Jun [Epub ahead of print])). Furthermore, the authors claim that these cells are capable of developing embryoid body-, oocyte- and blast-like structures in culture (Virant-Klun et al., (Virant-Klun, I. Zech, N. Rozman, P. Vogler, A. Cvjeticanin, B. Klemenc, P. Valicev, E. Meden-Vrtovec, H. (2008b). Putative stem cells with an embryonic character isolated from the ovarian surface epithelium of women with no naturally present follicles and oocytes. Differentiation 76, 843–856. Article)). Though there has been some evidence to suggest the existence of germ line stem cells and post-natal oogenesis, such cells do not appear to ovulate, are not found in the Fallopian tube, and do not contribute to pregnancies (Johnson et al., (2005); Eggan et al., (2006), reviewed in Tilly et al., (2008)).

5.2. Epithelial ovarian carcinoma

It is estimated that over 21,000 women will be diagnosed with ovarian carcinoma in 2008 and of these, approximately 15,000 will succumb to their disease (NCI SEER database: see [[UNSUPPORTED:p/uri]]). Survival is directly related to stage, with 5-year survival rates of 92.7% for those diagnosed with localized disease, to 30.6% for those with distant disease at diagnosis (NCI SEER). Unfortunately, two-thirds of patients already have evidence of distant disease at diagnosis (NCI SEER). While the majority of patients respond to initial therapy, most recur with chemoresistant disease. Hence re-evaluation of the current treatment paradigms of ovarian cancers is needed.

Cancer stem cells (CSC), or tumor-initiating cells, are postulated to be specialized cells within tumors which are responsible for propagating cancer growth (Al-Hajj and Clarke, (2004)). CSCs are thought to have the ability to give rise to daughter non-tumorigenic cancer cells while retaining their ability to self-renew and form tumors (Al-Hajj and Clarke, (2004)). Small populations of clonogenic cells capable of tumorigenesis, self-renewal, differentiation, and chemoresistance in vitro and in vivo have been identified as CSCs in a variety of solid tumors (Al-Hajj et al., (2003); Collins et al., (2005); Dalerba et al., (2007); Li et al., (2007)). There are several characteristics of epithelial ovarian carcinomas (EOCs) that indicate that it may be a stem cell-driven disease. Firstly, though the OSE is the postulated source of EOCs (Gondos, (1975); Herbst, (1994); Auersperg et al., (1998)), EOCs can generate differentiated subtypes that recapitulate the histology of other normal gynecologic tissues (Landen et al., (2008)). Secondly, the high rate of chemoresistant recurrence after initial treatment success suggests that there are cells within the cancer population which are 1) capable of repopulating then entire tumor burden from a small number of cells and 2) exhibit cytoprotective mechanisms thought to exist on somatic stem cells.

Less speculative, experimental evidence for the existence of ovarian cancer stem cells was first reported with the identification and isolation a single tumorigenic clone by anchorage independent spheroid formation from the ascites of a patient with advanced disease (Bapat et al., (2005)). The authors then went on to characterize this clone and provide immunohistologic evidence that suggested differentiation along epithelial, granulosa, and germ cell lineages. These clones were shown to form tumors and metastasize in nude mice and retained tumorigenic ability with sequential transplant (Bapat et al., (2005)). The authors concluded that their findings suggest that stem/progenitor cell-driven biology may contribute to the aggressive behavior of EOCs.

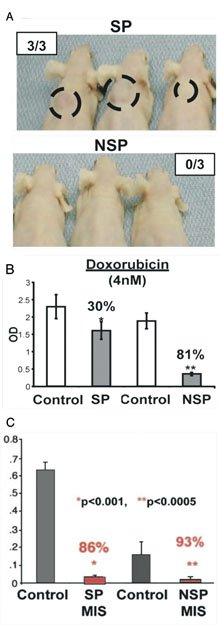

In a step further, by using the murine transgenic epithelial ovarian cancer cell line MOVCAR-7, produced when the large T antigen is driven by the Müllerian Inhibiting Substance type II receptor promoter (Connolly et al., (2003)), Szotek and colleagues identified a putative cancer stem cell within this cell line by using the dye efflux marker SP (Szotek et al., (2006)). This subset of cells were found to form palpable tumors when injected into the dorsal fat pad of nude mice, faster and at fewer inoculated numbers than the non-SP cells (see Figure 5A). The SP cells also were cell-cycle arrested and exhibited resistance to conventional chemotherapeutic agents whereas the non-SP cells were and did not (see Figure 5B). We also observed that Müllerian Inhibiting Substance, the protein responsible for the regression of the Müllerian duct during development, was able to inhibit the growth of these SP cells in vitro (see Figure 5C). Additionally, verapamil-sensitive SPs were identified in human ovarian cancer cell lines and in the ascites of a small number of patient, suggesting that the SP could be used to identify the CSC of ovarian cancers in patients though these human cells were not functionally characterized in this study.

Figure 5. Characterization of MOVCAR 7 side population cells. (A) Measurable tumors were detected in three of three SP-injected (at 5 × 105 cells) animals at 10 weeks after implantation, whereas zero of three NSP-injected animals demonstrated tumors at the first appearance of SP tumors. (B) SP cells showed only 30% inhibition by MTT assay (P< 4.2 × 10−4) while NSP cells were inhibited 81% (**P<5.1 × 10−10) by doxorubicin versus vehicle controls (shorter bars indicate more inhibition of cell growth). In contrast, (C) the proliferation of MOVCAR 7 SP and NSP cells also analyzed by MTT assay demonstrated inhibition of both SP (*86%) and NSP (**93%) cells by MIS versus vehicle control (shorter bars indicate more inhibition of cell growth). (Adapted with permission from Szotek, P.P., Pieretti-Vanmarcke, R., Masiakos, P.T., Dinulescu, D.M., Connolly, D., Foster, R., Dombkowski, D., Preffer, F., MacLaughlin, D.T., Donahoe, P.K. ((Szotek et al., 2006)). Ovarian cancer side population defines cells with stem cell-like characteristics and Müllerian Inhibiting Substance responsiveness. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 103, 11154–11159. Figures 3A, 4B, and 5E. Copyright 2006 National Academy of Sciences, U.S.A).

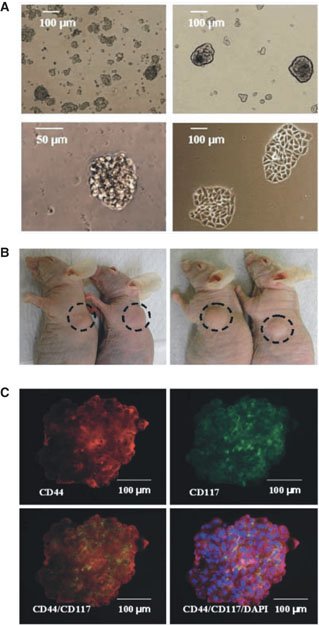

In the human, a recent study has identified a subpopulation of putative CSCs from primary human ovarian tumors (Zhang et al., (2008)). In this study, ovarian serous adenocarcinomas were disaggregated and grown in conditions selecting for anchorage independent spheroid formation (see Figure 6A). After several passages, purified sphere-forming cells were isolated and found to express various stem cell markers (stem cell factor, Notch-1, Nanog, ABCG2, and Oct-4), demonstrate chemoresistance to ovarian cancer therapeutics, and form palpable tumors in athymic nude mice with inoculation of as few as 100 purified cells (see Figure 6B) compared to no growth with injection of 1 × 106 non-spheroid cells. Further characterization of these cells identified an enrichment for the hyaluronate receptor CD44 and CD117 (c-kit) in the spheroid cells (see Figure 6C). The authors found that, similar to spheroid cells, CD44(+) CD117(+) cells isolated from primary human tumors were able to serially propagate the original tumor at injections of only 100 cells whereas up to 1×105CD44(-) CD117(-) cells formed no tumors. These findings lead the authors to assert that EOCs are derived from a CD44(+) CD117(+) CSC population.

Figure 6. Isolation and characterization of candidate human ovarian tumor cancer initiating cells form self-renewing, anchorage-independent spheroids under stem cell–selective conditions. (A) Cell suspensions form small, non-adherent clusters 1 wk after plating (top left). After ∼10 passages, 1% of spheres persist as larger, symmetric, prototypical spheroids (top right). Typical spheroids contained ∼100 cells and could be serially passaged for >6 mo (bottom left). Under differentiating conditions, sphere-forming cells adhere to plates and form symmetric holoclones (bottom right). (B) Injection of ∼100 OCICs per mouse from patient tumor 1 (left) or patient tumor 2 (right) dissociated spheroids generated xenograft tumors with 2/2 efficiency. (C) Staining of anti-CD44 monoclonal antibodies (red) in ovarian tumor spheroid (top left); immunofluorescence staining of anti-CD117 monoclonal antibodies (green) in ovarian tumor sphere cells (top right); CD44+ sphere cells colocalize with CD117+ cells (orange overlay, bottom left) and additionally stained with DAPI (blue; bottom right). Magnification, 200x. (Adapted with permission from Zhang, S., Balch, C., Chan, M.W., Lai, H.C., Matei, D., Schilder, J.M., Yan, P.S., Huang, T.H., Nephew, K.P. ((Zhang et al., 2008)). Identification and characterization of ovarian cancer-initiating cells from primary human tumors. Cancer Res 68, 4311–4320. Figures 1A, 3A and C.).

While the initial studies identifying and isolating CSCs in ovarian cancer have yielded valuable insight into the biology of this devastating disease, the therapeutic implications of these findings have yet to be realized. Further studies characterizing the CSC population in a wider population of patients with correlations made to stage at diagnosis, response to treatment, and, ultimately, survival are necessary to take the next step to design therapies targeting these specialized cells. In order to achieve sustained response and convert ovarian cancer to a manageable disease, it is apparent that treatment will need to be patient specific, cancer specific and stem cell specific.

Ovarian surface label retaining cells (green) were consistently found immediately adjacent to CD31+ vascular endothelial cells (red) after several months of chase (movie courtesy of Szotek, unpublished observation).

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Dr. Jose Teixeira for his critical reading of this text, Dr. Paul Szotek for the use of unpublished observations, and Ms. Caroline Coletti for her editorial expertise.

HLC was supported by NIH/MGH T32 in Cancer Biology # 2T32CA071345-11. DTM is supported by NIH/NCI Grant 5R01CA017393-30, the McBride Family Fund, the Commons Development Group, and the Ovarian Cancer Research Fund (New York). PKD is supported by Harvard Stem Cell Institute Grant DP-0010-07-00, Brigham and Women's SPORE Grant 5P50CA105009-03, and NIH/NCI Grant 5R01CA017393-33.

Copyright: © 2009 Henry L. Chang, David T. MacLaughlin, and Patricia K. Donahoe

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

§ To whom correspondence should be addressed. E-mail: pdonahoe@partners.org .

* Edited by Haifan Lin. Last revised April 02, 2009. Published April 30, 2009. This chapter should be cited as: Chang, H.L., MacLaughlin, D.T., and Donahoe, P.K., Somatic stem cells of the ovary and their relationship to human ovarian cancers (April 30, 2009), StemBook, ed. The Stem Cell Research Community, StemBook, doi/10.3824/stembook.1.43.1, [[UNSUPPORTED:p/uri]] .

References

- Ahmed, N. Thompson, E.W. Quinn, M.A. (2007). Epithelial-mesenchymal interconversions in normal ovarian surface epithelium and ovarian carcinomas: an exception to the norm. J Cell Physiol 213, 581–588. Abstract DOI

- Al-Hajj, M. Wicha, M.A. Benito-Hernandez, A. Morrison, S.J. Clarke, M.F. (2003). Prospective identification of tumorigenic breast cancer cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 100, 3983–3988. Abstract DOI

- Al-Hajj, M. Clarke, M.F. (2004). Self-renewal and solid tumor stem cells. Oncogene 23, 7274–7282. Abstract DOI

- Anderson, R. Reinhard, F. Georges-Labouesse, E. Hynes, R.O. Bader, B.L. Kreidberg, J.A. Schaible, K. Heasman, J. Wylie, C. (1999). Mouse primordial germ cells lacking beta1 integrins enter the germline but fail to migrate normally to the gonads. Development 126, 1655–1664. Abstract Abstract

- Auersperg, N. Edelson, M.I. Mok, S.C. Johnson, S.W. Hamilton, T.C. (1998). The biology of ovarian cancer. Semin Oncol 25, 281–304. Abstract Abstract

- Auersperg, N. Pan, J. Grove, B.D. Peterson, T. Fisher, J. Maines-Bandiera, S. Somasiri, A. Roskelley, C.D. (1999). E-cadherin induces mesenchymal-to-epithelial transition in human ovarian surface epithelium. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 96, 6249–6254. Abstract DOI

- Auersperg, N. Wong, A.S. Choi, K.C. Kang, S.K. Leung, P.C. (2001). Ovarian surface epithelium: biology, endocrinology, and pathology. Endocr Rev 22, 255–288. Abstract DOI

- Bapat, S.A. Mali, A.M. Koppikar, C.B. Kurrey, N.K. (2005). Stem and progenitor-like cells contribute to the aggressive behavior of human epithelial ovarian cancer. Cancer Res 65, 3025–3029. Abstract Abstract

- Behringer, R.R. Cate, R.L. Froelick, G.J. Palmiter, R.D. Brinster, R.L. (1990). Abnormal sexual development in transgenic mice chronically expressing Müllerian inhibiting substance. Nature 345, 167–170. Abstract DOI

- Boerboom, D. Paquet, M. Hseih, M. Liu, J. Jamin, S.P. Behringer, R.R. Sirois, J. Taketo, M.M. Richards, J.S. (2005). Misregulated Wnt/beta-catenin signaling leads to ovarian granulosa cell tumor development. Cancer Res 65, 9206–9215. Abstract DOI

- Bowles, J. Knight, D. Smith, C. Wilhelm, D. Richman, J. Mamiya, S. Yashiro, K. Chawengsaksophak, K. Wilson, M.J. Rossant, J. (2006). Retinoid signaling determines germ cell fate in mice. Science 312, 596–600. Abstract DOI

- Brennand, K. Huangfu, D. Melton, D. (2007). All beta cells contribute equally to islet growth and maintenance. Plos Biol 5, e163. Abstract DOI

- Buehr, M. McLaren, A. Bartley, A. Darling, S. (1993). Proliferation and migration of primordial germ cells in We/We mouse embryos. Dev Dyn 198, 182–189. Abstract Abstract

- Bukovsky, A. Kennan, J.A. Caudle, M.R. Wimalasena, J. Upadhyaya, N.B. Van Meter, S.E. (1995). Immunohistochemical studies of the adult human ovar: possible contribution of immune and epithelial factors to folliculogenesis. Am J Reprod Immunol 33, 323–340. Abstract Abstract

- Bukovsky, A. Caudle, M.R. Svetlikova, M. Upadhyaya, N.B. (2004). Origin of germ cells and formation of new primary follicles in adult human ovaries. Reprod Biol Endocrinol 2, 20. Abstract DOI

- Bukovsky, A. Gupta, S.K. Virant-Klun, I. Upadhyaya, N.B. Copas, P. Van Meter, S.E. Svetlikova, M. Ayala, M.E. Dominguez, R. (2008). Study origin of germ cells and formation of new primary follicles in adult human and rat ovaries. Methods Mol Biol 450, 233–265. Abstract DOI

- Byskov, A.G. Lintern-Moore, S. Follicle formation in the immature mouse ovary: the role of the rete ovarii. J Anat (1973). 116, 207–217. Abstract Abstract

- Chassot, A.A. Ranc, F. Gregoire, E.P. Roepers-Gajadien, H.L. Taketo, M.M. Camerino, G. de Rooij, D.G. Schedl, A. Chabiossier, M.C. (2008). Activation of beta-catenin signaling by Rspo1 controls differentiation o the mammalian ovary. Hum Mol Genet 17, 1264–1277. Abstract DOI

- Collins, A.T. Berry, P.A. Hyde, C. Stower, M.J. Maitland, N.J. (2005). Prospective identification of tumorigenic prostate cancer stem cells. Cancer Res 65, 10946–10951. Abstract DOI

- Colombo, N. Parma, G. Zanagnolo, V. Insinga, A. (2007). Management of ovarian stromal cell tumors. J Clin Oncol 25, 2944–2951. Abstract DOI

- Connolly, D.C. Bao, R. Nikitin, A.Y. Stephens, K.C. Poole, T.W. Hua, X. Harris, S.S. Vanderhyden, B.C. Hamilton, T.C. (2003). Female mice chimeric for expression of the simian virus 40 Tag under control of the MISIIR promoter develop epithelial ovarian cancer. Cancer Res 63, 1389–1397. Abstract Abstract

- Couse, J.F. Hewitt, S.C. Bunch, D.O. Sar, M. Walker, V.R. Davis, B.J. Korach, K.S. (1999). Postnatal sex reversal of the ovaries in mice lacking estrogen receptors alpha and beta. Science 286, 2328–2331. Abstract DOI

- Dalerba, P. Dylla, S.J. Park, I.K. Liu, R. Wang, X. Cho, R.W. Hoey, T. Gurney, A. Huang, E.H. Simeone, D.M. (2007). Phenotypic characterization of human colorectal cancer stem cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 104, 10158–10163. Abstract DOI

- De Felici, M. Scaldaferri, M.L. Farini, D. (2005). Adhesion molecules for mouse primordial germ cells. Front Biosci 10, 542–551. Abstract DOI

- Eggan, K. Jurga, S. Gosden, R. Min, I.M. Wagers, A.J. (2006). Ovulated oocytes in adult mice derive from non-circulating germ cells. Nature 441, 1109–1114. Abstract DOI

- Enomoto, T. Weghorst, C.M. Inoue, M. Tanizawa, O. Rice, J.M. (1991). K-ras activation occurs frequently in mucinous adenocarcinomas and rarely in other common epithelial tumors of the human ovary. Am J Pathol 139, 777–785. Abstract Abstract

- Ginsburg, M. Snow, M.H. McLaren, A. (1990). Primordial germ cells in the mouse embryo during gastrulation. Development 110, 521–528. Abstract Abstract

- Godin, I. Wylie, C. Heasman, J. (1990). Genital ridges exert long-range effects on mouse primordial germ cell numbers and direction of migration in culture. Development 108, 357–363. Abstract Abstract

- Gondos, B. (1975). Surface epithelium of the developing ovary. Possible correlation with ovarian neoplasia. Am J Pathol 81, 303–321. Abstract Abstract

- Goodell, M.A. Brose, K. Paradis, G. Conner, A.S. Mulligan, R.C. (1996). Isolation and functional properties of murine hematopoietic stem cells that are replicating in vivo. J Exp Med 183, 1797–1806. Abstract DOI

- Hajkova, P. Erhardt, S. Lane, N. Haaf, T. El0Maarri, O. Relk, W. Walter, J. Surani, M.A. (2002). Epigenetic reprogramming in mouse primordial germ cells. Mech Dev 117, 15–23. Abstract DOI

- Hajkova, P. Ancelin, K. Waldmann, T. Lacoste, N. Lange, U.C. Cesari, F. Lee, C. Almouzni, G. Schneider, R. Surani, M.A. (2008). Chromatin dynamics during epigenetic reprogramming in the mouse germ line. Nature 452, 877–881. Abstract DOI

- Hashimoto, N. Kubokawa, R. Yamazaki, K. Noguchi, M. Kato, Y. (1990). Germ cell deficiency causes testis cord differentiation in reconstituted mouse fetal ovaries. J Exp Zool 253, 61–70. Abstract DOI

- Herbst, A.L. (1994). The epidemiology of ovarian carcinoma and the current status of tumor markers to detect disease. Am J Obstet Gynecol 170, 1099–1105. Abstract Abstract

- Hirshfield, A.N. (1991). Theca cells may be present at the outset of follicular growth. Biol Reprod 44, 1157–1162. Abstract DOI

- Honda, A. Hirose, M. Hara, K. Matoba, S. Inoue, K. Miki, H. Hiura, H. Kanatsu-Shinohara, M. Kanai, Y. Kono, T. (2007). Isolation, characterization, and in vitro and in vivo differentiation of putative thecal stem cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 104, 12389–12394. Abstract DOI

- Johnson, J. Bagley, J. Skaznik-Wikiel, M. Lee, H.J. Adams, G.B. Niikura, Y. Tschudy, K.S. Tilly, J.C. Cortes, M.L. Forkert, R. (2005). Oocyte generation in adult mammalian ovaries by putative germ cells in bone marrow and peripheral blood. Cell 122, 303–315. Abstract DOI

- Jonker, J.W. Freeman, J. Bolscher, E. Musters, S. Alvi, A.J. Titley, I. Schinkel, A.H. Dale, T.C. (2005). Contribution of the ABC transporters Bcrp1 and Mdr1a/1b to the side population phenotype in mammary gland and bone marrow of mice. Stem Cells 23, 1059–1065. Abstract DOI

- Kimmins, S. Sassone-Corsi, P. (2005). Chromatin remodeling and epigenetic features of germ cells. Nature 434, 583–589. Abstract DOI

- Konishi, I. Fujii, S. Okamura, H. Parmley, T. Mori, T. (1986). Development of interstitial cells and ovigerous cords in the human fetal ovary: an ultrastructural study. J Anat 148, 121–135. Abstract Abstract

- Koubova, J. Menke, D.B. Zhou, Q. Capel, B. Griswold, M.D. Page, D.C. (2006). Retinoic acid regulates sex-specific timing of meiotic initiation in mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 103, 2474–2479. Abstract DOI

- Kruk, P.A. Auersperg, N. (1992). Human ovarian surface epithelial cells are capable of physically restructuring extracellular matrix. Am J Obstet Gynecol 167, 1437–1443. Abstract Abstract

- Kruk, P.A. Auersperg, N. (1994). A line of rat ovarian surface epithelium provides a continuous source of complex extracellular matrix. In Vitro Cell Dev Biol Anim 30A, 217–225. Abstract DOI

- Landen, C.N. Birrer, M.J. Sood, A.K. (2008). Early events in the pathogenesis of epithelial ovarian cancer. J Clin Oncol 26, 995–1005. Abstract DOI

- Lawson, K.A. Dunn, N.R. Roelen, B.A. Zeinstra, L.M. Davis, A.M. Wright, C.V. Korving, J.P. Hogan, B.L. (1999). Bmp4 is required for the generation of primordial germ cells in the mouse embryo. Genes Dev 13, 424–436. Abstract DOI

- Lee, J. Inoue, K. Ono, R. Ogonuki, N. Kohda, T. Kaneko-Ishino, I. Ogura, A. Ishino, F. (2002). Erasing genomic imprinting memory in mouse clone embryos produced from day 11.5 primordial germ cells. Development 129, 1807–1817. Abstract DOI

- Li, C. Heidt, D.G. Dalerba, P. Burant, C.F. Zhang, L. Adsay, V. Wicha, M. Clarke, M.F. Simeone, D.M. (2007). Identification of pancreatic cancer stem cells. Cancer Res 67, 1030–1037. Abstract DOI

- Liang, S.B. Sonobe, H. Taguchi, T. Takeuchi, T. Furihata, M. Yuri, K. Ohtsuki, Y. (2001). Terasomy 12 in ovarian tumors of thecoma-fibroma group: A fluorescence in situ hybridization analysis using paraffin sections. Pathol Int 51, 37–42. Abstract DOI

- Loffler, K.A. Koopman, P. (2002). Charting the course of ovarian development in vertebrates. Int J Dev Biol 46, 501–510.

- Maatouk, D.M. Dinapoli, L. Alvers, A. Parker, K.L. Taketo, M.M. Capel, B. (2008). Stabiliztion of {beta}-catenin in XY gonads causes male-to-female sex-reversal. Hum Mol Genet 17, 2949–2955. Abstract DOI

- Mahdavi, A. Pejovic, T. Nezhat, F. (2006). Induction of ovulatio and ovarian cancer: a critical review of the literature. Fertil Steril 85, 819–826. Abstract DOI

- Merchant-Larios, H. Centeno, B. (1981). Morphogenesis of the ovary from the sterile W/Wv mouse. Prog Clin Biol Res 598, 383–392.

- Merchant-Larios, H. Chimal-Monroy, J. (1989). The ontogeny of primordial follicles in the mouse ovary. Prog Clin Biol Res 296, 55–63. Abstract Abstract

- Molyneaux, K.A. Zinszner, H. Kunwar, P.S. Schaible, K. Stebler, J. Sunshine, M.J. O’Brien, W. Raz, E. Littman, D. Wylie, C. Lehmann, R. (2003). The chemokine SDF1/CXCL12 and its receptor CXCR4 regulate mouse germ cell migration and survival. Development 130, 4279–4286. Abstract DOI

- Molyneaux, K.A. Wylie, C. (2004). Primordial germ cell migration. Int J Dev Biol 48, 537–544. Abstract DOI

- Odor, D.L. Blandau, R.J. (1969). Ultrastructural studies on fetal and early postnatal ovaries. II. Cytodifferentiation. Am J Anat 125, 177–215. Abstract DOI

- Ohinata, Y. Payer, B. O’Carroll, D. Ancelin, K. Ono, Y. Sano, M. Barton, S.C. Obukhanych, T. Nussenzweig, M. Tarakhovsky, A. (2005). Blimp1 is a critical determinant of the germ cell lineage in mice. Nature 436, 207–213. Abstract DOI

- Oktem, O. Oktay, K. (2008). The ovary: anatomy and function throughout human life. Ann NY Acad Sci 1127, 1–9. Abstract DOI

- Ono, M. Maruyama, T. Masuda, H. Kajitani, T. Nagashima, T. Arase, T. Ito, M. Ohta, K. Uchida, H. Asada, H. Side population in human uterine myometrium displays phenotypic and functional characteristics of myometrial stem cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA (2007). 104, 18700–18705. Abstract DOI

- Ottolenghi, C. Omari, S. Garcia-Ortiz, J.E. Uda, M. Crisponi, L. Forabosco, A. Pillia, G. Schlessinger, D. (2005). Foxl2 is required for commitment to ovary differentiation. Hum Mol Genet 14, 2053–2062. Abstract DOI

- Pepling, M.A. Spralding, A.C. (1998). Female mouse germ cells form synchronously dividing cysts. Development 125, 3323–3328. Abstract Abstract

- Pinkerton, J.H. McKay, D.G. Adams, E.C. Hertig, A.T. (1961). Development of the human ovary—a study using histochemical techincs. Obstet Gynecol 18, 152–181. Abstract Abstract

- Reik, W. Walter, J. (2001). Genomic imprinting: parental influence on the genome. Nat Rev Genet 2, 21–32. Abstract DOI

- Rossi, D.J. Jamieson, C.H. Weissman, I.L. (2008). Stem cells and the pathways to aging and cancer. Cell 132, 681–696. Abstract DOI

- Saitou, M. Barton, S.C. Surani, M.A. (2002). A molecular programme for the specification of germ cell fate in mice. Nature 418, 293–300. Abstract DOI

- Sawyer, H.R. Smith, P. Heath, D.A. Juengel, J.L. Wakefield, S.J. McNatty, K.P. (2002). Formation of ovarian follicle during fetal development in sheep. Biol Reprod 66, 1134–1150. Abstract DOI

- Schmidt, D. Ovitt, C.E. Anlag, K. Fesenfeld, S. Gredsted, L. Teier, A.C. Treier, M. (2004). The murine winged-helix transcription factor Foxl2 is required for granulosa cell differentiation and ovary maintenance. Development 131, 933–942. Abstract DOI

- Schneider, D.T. Schuster, A.E. Fritsch, M.K. Hu, J. Olson, T. Lauer, S. Göbel, U. Perlman, E.J. (2001). Multipoint imprinting analysis indicates a common precursor cell for gonadal and nongonadal pediatric germ cell tumors. Cancer Res 61, 7268–7276. Abstract Abstract

- Schumer, S.T. Cannistra, S.A. (2003). Granulosa cell tumor of the ovary. J Clin Oncol 21, 1180–1189. Abstract DOI

- Seki, Y. Hayashi, K. Itoh, K. Mizugaki, M. Saitou, M. Matsui, Y. (2005). Extensive and orderly reprogramming of genome-wide chromatin modification associated with specification and early development of germ cells in mice. Dev Biol 278, 440–458. Abstract DOI

- Seki, Y. Yamaji, M. Yabuta, Y. Sano, M. Shigeta, M. Matsui, Y. Saga, Y. Tachibana, M. Shinkai, Y. Saitou, M. (2007). Cellulary dynamics associate with the genome-wide epigenetic reprogramming in migrating primordial germ cells in mice. Development 134, 2627–2638. Abstract DOI

- Semczuk, A. Postawski, K. Przadka, D. Rozynska, K. Wrobel, A. Korobowicz, E. (2004). K-ras gene point mutations and p21ras immunostaining in human ovarian tumors. Eur J Gynaecol Oncol 25, 484–488. Abstract Abstract

- Shashi, V. Golden, W.L. von Kap-Herr, C. Andersen, W.A. Gaffey, M.J. (1994). Interphase fluorescence in situ hybridization for trisomy 12 on archival ovarian sex cord-stromal tumors. Gynecol Oncol 55, 349–354. Abstract DOI

- Shen, Y. Mamers, P. Jobling, T. Burger, H.G. Fuller, P.J. (1996). Absence of the previously reported G protein oncogene (gip2) in ovarian granulosa cell tumors. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 81, 4159–4161. Abstract DOI

- Streblow, R.C. Dafferner, A.J. Nelson, M. Fletcher, M. West, W.W. Stevens, R.K. Gatalica, Z. Novak, D. Bridge, J.A. (2007). Imbalances of chromosomes 4, 9, and 12 are recurrent in the thecoma-fibroma group of ovarian stromal tumors. Cancer Genet Cytogenet 178, 135–140. Abstract DOI

- Swain, A. Lovell-Badge, R. (1999). Mammalian sex determination: a molecular drama. Genes Dev 13, 755–767. Abstract DOI

- Szotek, P.P. Pieretti-Vanmarcke, R. Masiakos, P.T. Dinulescu, D.M. Connolly, D. Foster, R. Dombkowski, D. Preffer, F. MacLaughlin, D.T. Donahoe, P.K. (2006). Ovarian cancer side population defines cells with stem cell-like characteristics and Müllerian Inhibiting Substance responsiveness. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 103, 11154–11159. Abstract DOI

- Szotek, P.P. Chang, H.L. Brennand, K. Fujino, A. Pieretti-Vanmarcke, R. Lo Ceslo, C. Dombkowski, D. Preffer, F. Cohen, K.S. Teixeira, J. Donahoe, P.K. (2008). Normal ovarian surface epithelial label-retaining cells exhibit stem/progenitor cell characteristics. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 105, 12469–12473. Abstract DOI

- Taketo, T. Saeed, J. Manganaro, T. Takahashi, M. Donahoe, P.K. (1993). Müllerian Inhibiting Substanc production associated with loss of oocytes and testicular differentiation in the transplanted mouse XX gonadal primordium. Biol Reprod 49, 13–23. Abstract DOI

- Tam, P.P. Snow, M.H. (1981). Proliferation and migration of primordial germ cells during compensatory growth in mouse embryos. J Embryol Exp Morphol 64, 133–147. Abstract Abstract

- Tilly, J.L. Niikura, Y. Rueda, B.R. (2008). The current status of evidence for and against postnatal oogenesis in mammals: a case of ovarian optimism versus pessimism?. Biol Reprod Aug 27 [Epub ahead of print] Abstract Abstract

- Tumbar, T. Guasch, G. Greco, V. Blanpain, C. Lowry, W.E. Rendl, M. Fuchs, E. (2004). Defining the epithelial stem cell niche in skin. Science 303, 359–363. Abstract DOI

- Uda, M. Ottolenghi, C. Crisponi, L. Garcia, J.E. Deiana, M. Kimber, W. Forabosco, A. Cao, A. Schlessinger, D. Pillia, G. (2004). Foxl2 disruption causes mouse ovarian failure by pervasive blockage of follicle development. Hum Mol Genet 13, 1171–1181. Abstract DOI

- Vainio, S. Heikkilä, M. Kispert, A. Chin, N. McMahon, A.P. (1999). Female development in mammals is regulated by Wnt-4 signaling. Nature 397, 405–409. Abstract DOI

- Virant-Klun, I. Rozman, P. Cvjeticanin, B. Vrtacnik, . Bokal, E. Novakovic, S. Ruelicke, T. (2008a). Parthenogenetic embryo-like structures in the human ovarian surface epithelium cell culture in postmenopausal women with no naturally present follicles and oocytes. Stem Cells Dev 7 Jun [Epub ahead of print]

- Virant-Klun, I. Zech, N. Rozman, P. Vogler, A. Cvjeticanin, B. Klemenc, P. Valicev, E. Meden-Vrtovec, H. (2008b). Putative stem cells with an embryonic character isolated from the ovarian surface epithelium of women with no naturally present follicles and oocytes. Differentiation 76, 843–856. Article DOI

- Yao, H.H. Matzuk, M.M. Jorgez, C.J. Menke, D.B. Page, D.C. Swain, A. Capel, B. (2004). Follistatin operates downstream of Wnt4 in mammalian ovary organogenesis. Dev Dyn 230, 210–215. Abstract DOI

- Ying, Y. Liu, X.M. Marble, A. Lawson, K.A. Zhao, G.Q. (2000). Requirement of Bmp8b for the generation of primordial germ cells in the mouse. Mol Endocrinol 14, 1053–1063. Abstract DOI

- Zhang, S. Balch, C. Chan, M.W. Lai, H.C. Matei, D. Schilder, J.M. Yan, P.S. Huang, T.H. Nephew, K.P. (2008). Identification and characterization of ovarian cancer-initiating cells from primary human tumors. Cancer Res 68, 4311–4320. Abstract DOI