While many clinician- and industry-led autologous cellular therapies are demonstrating benefits to patients in clinical trials, few products have been commercially approved. Progress towards production and commercialization still faces substantial translational challenges under existing regulatory frameworks. Manufacturing and supply of more-than-minimally manipulated (MTMM) autologous cell based therapies presents a number of unique challenges driven by complex supply logistics and the need to scale-out production to multiple manufacturing sites or potentially near to the patient within hospital settings. The existing regulatory structure in Europe and the U.S imposes a requirement to establish and maintain comparability. Under a single market authorisation this is likely to become an insurmountable burden for the roll-out of manufacturing processes to more than two or three sites unless new enabling manufacturing and regulatory science can be established to bridge the comparability challenge.

1. Introduction

Cell based therapies fall into two broad classes, those derived from a patient's own cells (autologous or ‘one to one’ therapies) and those derived from a donor's cells (allogeneic or ‘one to many’ therapies). This distinction drives the product safety and efficacy model and the approaches to manufacturing, transportation and clinical delivery of the product. In turn, this dictates the technical and regulatory challenges for developing and commercialising safe, effective and reproducible cell based therapies at the required scale and cost.

Over the last ten years there has been a steady increase in the clinical development of autologous cell products. An increasing number of clinician- and industry-led autologous cellular therapies are demonstrating benefits to patients in pivotal or late stage clinical trials in many therapeutic areas, including cardiovascular disease, peripheral arterial disease, liver disease, diabetes, neurodegenerative disorders, bone repair, and spinal cord injuries (see Section 3 of this Chapter). However, if these products are to progress further down the development pipeline, a number of specific challenges associated with their manufacturing and supply need to be overcome to permit the scale/roll-out of autologous treatments under existing regulatory frameworks. This review focusses on how the existing regulations impact the development and commercialization of autologous cell therapy products. Particular emphasis is placed on the specific challenges for the manufacture and scale-out of more-than-minimally manipulated (MTMM) autologous cell based therapies to multiple manufacturing sites or potentially near to the patient within hospital settings.

2. Manufacturing and supply approaches

Manufacturing and supply of autologous cell based therapies presents a number of specific and additional challenges. As distinct from allogeneic therapy or traditional pharmaceuticals/biologics production, this is driven by complex supply logistics and the need to scale-out (replicating the manufacturing line or unit operation to increase the number of batches) rather than scale-up production (increasing manufacturing output by increasing the volume or number of cells processed for each batch).

Most companies seeking highly profitable business models work predominantly with scalable allogeneic therapies following a business and supply model similar to that of the conventional biopharmaceuticals ((Williams et al., 2012); (Foley et al., 2012)). Smaller scale autologous therapies need to follow alternative manufacturing and distribution approaches, dependent on the product (disease indication and prevalence), the method of preservation of the product and the fit with the systems in place at the final destination in the clinic ((Mason, C. Dunhill, P. 2009Assessing the value of autologous and allogeneic cells for regenerative medicineRegenerative Medicine 46835–853 [doi: 10.2217/rme.09.64] [pmid: 19903003]); (McKernan et al., 2010); (McCall, M. Williams, D.J. 2012What are the alternative manufacturing and supply models available to Regenerative Medicine companies and how do the finance stack up? VALUE Project Final Report: Regenerative medicine value systems: Navigating the uncertainties, p55-65. Available at: http://www.biolatris.com/Biolatris/News_&_events_files/VALUE%20Final%20Report.pdf)).

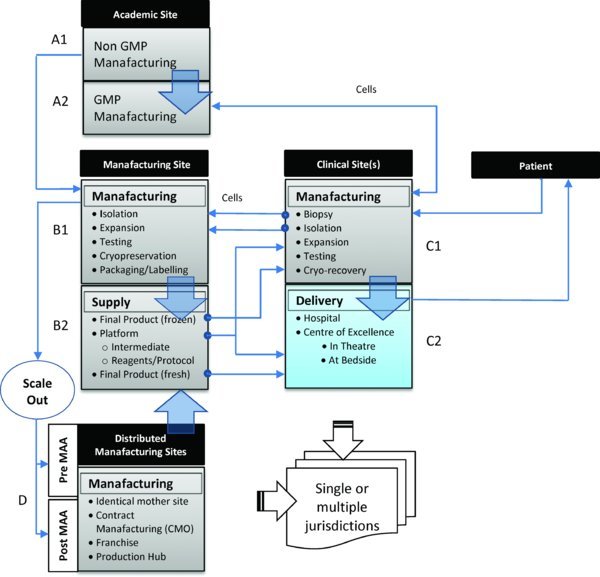

Approaches may involve a central processing facility serving a number of clinical sites and which require patients to travel to a specialised centre for treatment (e.g. Tigenix have used this approach for ChondroCelect®). They may involve a distributed model that requires localised processing within a hospital unit or manufacturing in-theatre or at the bedside, in which cells are removed from patients and processed locally by means of a closed or functionally closed, automated processing system or device before being reintroduced into patient on-site (Figure 1). Allowing bedside isolation and enrichment of cells for treatment of a range of conditions, commercial examples of these near patient or point-of-care processing devices are already in use, for example, CliniMACs® Prodigy (Miltenyi Biotec), Cellution® (Cytori Therapeutics Inc.) and HiQCell (Regeneus Ltd). So far these have primarily been used for cell therapy products that are not regulated as medicinal products i.e. the cells are not substantially modified or altered and are used in a form similar to their original function ((McKernan et al., 2010); (Bravery, C.A. 2012Regulation: What are the real uncertainties? VALUE Project Final Report: Regenerative medicine value systems: Navigating the uncertainties, p35–46. Available at: http://www.biolatris.com/Biolatris/News_&_events_files/VALUE%20Final%20Report.pdf)).

Figure 1. Alternative routes for manufacturing, distribution and delivery of small scale more-than-minimally manipulated autologous cell therapy products. Approaches may involve (i) a regulated central processing facility (B1 or A2) serving a number of clinical sites in which the patient travels to the clinical site/specialised centre for treatment. Cells are removed from the patient (C1) and transferred to the regulated manufacturing site (B1 or A2) before being returned back to the clinical site for administration to the patient either directly as fresh product (C2) or following further processing (cryo-recovery) (C1) or (ii) a distributed model that requires localised processing within a hospital unit (C1) or manufacturing in-theatre or at the bedside (C2), in which cells are removed from patients and processed locally by means of a closed, automated processing system(s) before being reintroduced into the patient on-site. The origin and scale of the potential routes for manufacturing scale/roll-out to multiple sites may involve transfer of a manufacturing process and product (iii) from an academic (A1) or hospital laboratory (C1) to a regulated manufacturing site (B1 or A2); (iv) to one or more additional production lines within the same facility or to a regulated manufacturing site(s) (D) within the same jurisdiction, either before or after Phase III clinical trials (i.e. pre- or post-Marketing Authorisation Application (MAA)) or to regulated manufacturing site(s) within different jurisdictions, or (v) to processing sites in International Clinical Centres of Excellence for major clinical specialisms (C2). Potential routes may also involve the roll-out of self-contained manufacturing platforms, standardised reagents and protocols (B2) close to the clinic (C2) or to local production hubs (D).

3. Clinical and industrial landscape

Research and development in cell based therapies is maturing ((Fisher et al., 2013)) but large conventional pharmaceutical companies are seemingly reluctant to engage in ‘high risk’ early investigational phases of their development ((McKernan et al., 2010)). There is however some evidence that this is beginning to change ((House of Lords Science and Technology Committee: Regenerative Medicine Report. 2013(London: The Stationary Office) Available at: http://www.publications.parliament.uk/pa/ld201314/ldselect/ldsctech/23/23.pdf); (Mason et al., 2013)).

3.1. Clinical pipeline of cell therapies

In Europe, the major stakeholders developing Advanced Therapy Medicinal Products (ATMPs) are hospitals, academic institutions, charities, and Small and Medium sized Enterprises (SMEs) ((Maciulaitis et al., 2012); (House of Lords Science and Technology Committee: Regenerative Medicine Report. 2013(London: The Stationary Office) Available at: http://www.publications.parliament.uk/pa/ld201314/ldselect/ldsctech/23/23.pdf)). Academic and clinical centres with Good Manufacturing Practice (GMP) compliant facilities are also becoming more common across Europe and the U.S. These are now significant contributors to the translation of cell therapy research to GMP compliant protocols and for the provision of non-clinical and clinical trial GMP-grade material ((Maciulaitis et al., 2012); (Culme-Seymour et al., 2012); Cell Therapy Catapult, 2013; (Pearce et al., 2014))

The development of new ATMPs is largely investigator-led in the EU and U.S with Europe lagging behind the U.S in terms of the cellular therapies in clinical trials. Recent analysis by (Foley et al., 2012) has shown that an increasing number of clinician-led (i.e. clinical trials sponsored by an institution), predominantly autologous cellular therapies, are demonstrating benefits to patients. These clinician-led therapies span those where a degree of clinical adoption and proven efficacy already exists to those where trials will be carried out under regulatory constraints more familiar to company-led cellular therapies. In their study, (Foley et al., 2012) identified two prominent groups of the cellular therapies in development. Clinician-led autologous cellular therapies that focus primarily on procedures (defined as cell therapies with complex routes of administration) represented 63% of all clinician-led trials (437). Company-led cellular therapies that were primarily allogeneic and product-focused (defined as cell therapies where intervention is minimal) represented 44% of all company-led trials (66). Overall, of the 503 trials sampled, an estimated 87% were led by clinicians and 13% by companies. Of all the trials (involving both procedures and products), 71% were autologous (355) and of these only 22 (6%) were company-led.

According to industry data compiled by the Cell Therapy Group ((Buckler, L. 2012Late-stage industry-sponsored cell therapy trials Available at: http://celltherapyblog.blogspot.ca/2011/12/active-phase-iii-or-iiiii-cel-therapy.html)), as of August 2012, there were 48 industry-sponsored (40 companies) clinical trials of cell therapies in pivotal or late stages (Phase III or PhaseII/III), of which 59% were autologous. From a U.S perspective, a recent report from the Pharmaceutical Research and Manufacturers of America ((Pharmaceutical Research and Manufacturers of America (PhRMA). 2013Medicines in Development Biologics 2013 Report (Washington: PhRMA) Available at: http://www.phrma.org/sites/default/files/pdf/biologics2013.pdf [pmid: 24113428])), which lists all U.S industrial sponsored biologics in clinical trials, identified 69 cell therapies in clinical trials or under review by the U.S Food and Drug Administration (U.S FDA). Fifteen were in Phase III clinical trials, of which six were autologous. From a UK perspective, as one of the leading countries in Europe developing ATMPs alongside Germany and Spain ((Maciulaitis et al., 2012)), as of April 2013 there were 34 cell therapy clinical trials (mainly Phase I/II or II) ongoing in the UK, of which 23 were autologous (68%). The majority (76%) of clinical trials were sponsored by a research institution with only 6 sponsored by industry (Cell Therapy Catapult, 2013). These trends are consistent with a recent analysis of ATMP development in Europe ((Maciulaitis et al., 2012)).

3.2. Industrial snapshot of the autologous cell therapy field

Despite the rich pipeline of cell therapies that are in clinical development, only a limited number have been taken down the established regulatory pathway for cellular products and translated into products for market approval. Since 2009 there have only been 12 approvals; six in the U.S, one in Europe, one in Canada, one in New Zealand and three in South Korea ((Buckler, L. 2012Late-stage industry-sponsored cell therapy trials Available at: http://celltherapyblog.blogspot.ca/2011/12/active-phase-iii-or-iiiii-cel-therapy.html); (Alliance for Regenerative Medicine (ARM). 2013Regenerative Medicine Annual Report March 2012 - March 2013 (Washington: ARM) Available at: http://alliancerm.org/news/download-must-have-industry-report)). Very few of these are autologous cell therapies.

Currently, MACI (matrix-induced autologous chondrocyte implantation), intended for the repair of cartilage defects (Genzyme/Sanofi, France) and ChondroCelect® (TiGenix, Belgium) are the only licenced cell-based ATMPs on the market in Europe. Licensed by the European Medicines Agency (EMA) in 2009, ChondroCelect® (TiGenix) as the first ATMP, is likely to set the standard for the clinical development of cell based therapeutics ((Warren et al., 2013)). In the U.S, three autologous cell therapies have been approved. Carticel® (autologous chondrocytes for cartilage repair) was the first approved product in 1997 (Genzyme/Sanofi). An autologous treatment for prostate cancer (Provenge®; Dendreon) was approved in 2010 and has been developed with a multiple manufacturing site model in mind. In addition, an autologous fibroblast product for filling wrinkles was approved in 2012 (laViv; Fibrocell). In South Korea, two autologous programmes have received approval in the past few years, an autologous bone marrow–derived cell therapy for myocardial infarction in 2011 (HeartiCellgram®-AMI; PharmiCell Co. Ltd) and an adipose tissue–derived cell therapy for anal fistulas in 2012 (Cupistem; Anterogen). It is worth noting that limited peer-reviewed clinical trial data for these products are publically available ((Wohn et al., 2012); (Bersenev, A. 2012Stem cell therapy industry is booming in Korea Available at: http://stemcellassays.com/2012/07/stem-cell-industry-korea/ [pmid: 22679445])).

4. Regulatory pathway for autologous cell therapies

The regulatory approach taken for specific autologous cell therapies is dictated by their intended clinical use, method of clinical delivery and manufacture. In some therapeutic cases, particularly in the orthopaedic and cosmetic sectors, harvested cells are minimally manipulated (e.g. by aseptic enrichment or separation techniques) and returned to the same patient. In most others there is a requirement to expand the number of harvested cells in in vitro culture to generate a sufficient dose for therapeutic use. This expansion in culture, being considered by regulators to be more than minimal (or substantial) manipulation, raises considerable hurdles and challenges for both developers and regulators ((Ahrlund-Richter et al., 2009); (Committee for Advanced Therapies (CAT) and CAT Scientific Secretariat. Challenges with ATMPs and how to meet them. 2010) Nature Review Drug Discovery; 9195201); (Salmikangas et al., 2011); (Van Wilder et al., 2012); (Bravery, C.A. 2012Regulation: What are the real uncertainties? VALUE Project Final Report: Regenerative medicine value systems: Navigating the uncertainties, p35–46. Available at: http://www.biolatris.com/Biolatris/News_&_events_files/VALUE%20Final%20Report.pdf)).

Under the existing regulatory framework, cellular products that have been subject to more-than-minimal manipulation and/or do not carry out the same function in the recipient as the donor (non-homologous use) are broadly classified as either medicinal products (EU) or biologics (U.S). Relatively few regulatory distinctions are made between autologous and allogeneic therapies and the characteristics that differentiate them ((U.S FDA. 2001 Title 21 of the Code of Federal Regulations (CFR) Part 1271 Human Cells, Tissues and Cell and Tissue Based Products); (European Commission. 2007 Regulation 1394/2007 for Advanced Therapy Medicinal Products)). In the EU and U.S, the use of such cell based medicinal products is regulated under Public health legislation and Pharmaceutical legislation. Other related legal requirements and guidelines are applicable across each stage of the product development process. For a summary of the EU and U.S legislation applicable to the development and use of human cells and tissues in human therapeutics, readers are directed to the Publically Available Specification (PAS 83:2012) published by the British Standards Institution ((British Standards Institution (BSI). 2012PAS 83:2012. Developing human cells for clinical applications in the European Union and the United States of America – Guide Published by BSI Standards Ltd 2012. Available at: http://shop.bsigroup.com/forms/PASs/PAS-83/)).

The regulatory route is determined by criteria which differ between the EU and the U.S. In the U.S, cell-based biologics are regulated by the Center for Biologics Evaluation and Research under Title 21 of the Code of Federal Regulations (CFR) Part 1271 as Human Cells, Tissues and Cell and Tissue-based Products (HCT/Ps) and must gain approval from the FDA via the submission of a Biologics Licence Application (BLA) ((U.S FDA. 2001 Title 21 of the Code of Federal Regulations (CFR) Part 1271 Human Cells, Tissues and Cell and Tissue Based Products)). Once submitted, a BLA is subject to review by the FDA (6-10 months) to assess the quality, safety and efficacy of the product. The FDA is responsible for all facets of regulating cell-based therapies, including clinical trial authorisation and compliance with the current Good Manufacturing Practice (cGMP) requirements. The situation in Europe is somewhat more complex.

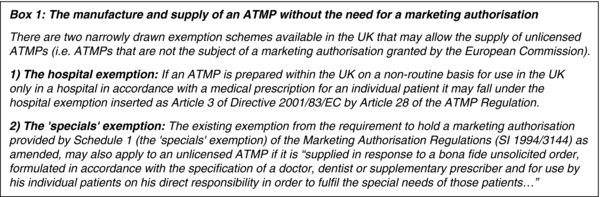

In Europe, cell-based medicinal products are regulated under the Advanced Therapy Medicinal Product (ATMP) Regulation ((European Commission. 2007 Regulation 1394/2007 for Advanced Therapy Medicinal Products)), which mandates that all ATMPs are subject to a centralised marketing authorisation procedure. All marketing authorisation applications are subject to a 210-day assessment procedure by the EMA, supported by the Committee for Advanced Therapies (CAT), before a licence can be granted. Member states still retain responsibility for authorisation of clinical trials occurring within their borders, and have the option to exempt certain products used on a non-routine basis for unmet clinical need (in particular the ‘Hospital Exemption’).

In the UK, the Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency (MHRA) is the supervisory authority for UK manufacturers or importers of centrally authorised ATMPs. The MHRA is the competent authority for ATMPs that are prepared and used under the Hospital Exemption and made and supplied under the ‘Specials’ scheme (see Box 1). It is also the competent authority for the assessment of applications for clinical trial authorisations and the associated manufacturer's licence for investigational ATMPs.

5. Regulatory challenges for the manufacture of MTMM autologous cell therapies

5.1. Regulatory harmonisation

5.2. Point-of-care manufacturing

5.3. Multisite manufacture – the hidden challenge of comparability

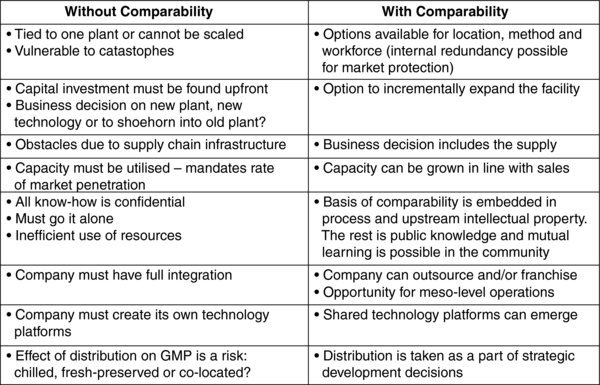

Table 1. Manufacturing strategies for MTMM autologous cell based products from the perspective of process development with and without a proportionate approach to comparability.

6. Future perspectives – the need for regulatory debate

Acknowledgements

References

- Ahrlund-Richter, L. De Luca, M. Marshak, D.R. Munsie, M. Viega, A. Rao, M. (2009). Isolation and production of cells suitable for human therapy: Challenges ahead. Cell Stem Cell 4, 20–26. Article Abstract Abstract DOI

- Alliance for Regenerative Medicine (ARM). 2013Regenerative Medicine Annual Report March 2012 - March 2013 (Washington: ARM) Available at: http://alliancerm.org/news/download-must-have-industry-report

- Bersenev, A. 2012Stem cell therapy industry is booming in Korea Available at: http://stemcellassays.com/2012/07/stem-cell-industry-korea/ [pmid: 22679445]

- Bravery, C.A. 2012Regulation: What are the real uncertainties? VALUE Project Final Report: Regenerative medicine value systems: Navigating the uncertainties, p35–46. Available at: http://www.biolatris.com/Biolatris/News_&_events_files/VALUE%20Final%20Report.pdf

- British Standards Institution (BSI). 2012PAS 83:2012. Developing human cells for clinical applications in the European Union and the United States of America – Guide Published by BSI Standards Ltd 2012. Available at: http://shop.bsigroup.com/forms/PASs/PAS-83/

- Buckler, L. 2012Late-stage industry-sponsored cell therapy trials Available at: http://celltherapyblog.blogspot.ca/2011/12/active-phase-iii-or-iiiii-cel-therapy.html

- Committee for Advanced Therapies (CAT) and CAT Scientific Secretariat. Challenges with ATMPs and how to meet them. 2010) Nature Review Drug Discovery; 9195201

- Culme-Seymour, E.J. Davie, L.N. Brindley, D.A. Edwards-Parton, S. Mason, C. (2012). A decade of cell therapy clinical trials (2000–2010). Regenerative Medicine 7(4), 455–462. Article Abstract Abstract DOI

- European Commission. 2007 Regulation 1394/2007 for Advanced Therapy Medicinal Products

- Fisher, M.B. Mauck, R.L. (2013). Tissue engineering and regenerative medicine: recent innovations and the transition to translation. Tissue Engineering, Part B Rev 19(1), 1–13. Article Abstract Abstract DOI

- Foley, L. Whitaker, M. (2012). Concise Review: Cell Therapies: The route to widespread adoption. Stem Cells Translational Medicine 1, 438–447. Article Abstract Abstract DOI

- House of Lords Science and Technology Committee: Regenerative Medicine Report. 2013(London: The Stationary Office) Available at: http://www.publications.parliament.uk/pa/ld201314/ldselect/ldsctech/23/23.pdf

- Maciulaitis, R. D’Apote, L.D. Buchanan, A. Pioppo, L. Schneider, C.K. (2012). Clinical development of advanced therapy medical products in Europe: Evidence that regulators must be proactive. Molecular Therapy 20(3), 479–482. Abstract Abstract

- Mason, C. Mason, J. Culme-Seymour, E.J. Bonfiglio, G.A. Reeve, B.C. (2013). Cell therapy companies make strong progress from October 2012 to March 2013 amid mixed stock market sentiment. Cell Stem Cell 12(6), 644–647. Abstract Abstract

- Mason, C. Dunhill, P. 2009Assessing the value of autologous and allogeneic cells for regenerative medicineRegenerative Medicine 46835–853 [doi: 10.2217/rme.09.64] [pmid: 19903003]

- McCall, M. Williams, D.J. 2012What are the alternative manufacturing and supply models available to Regenerative Medicine companies and how do the finance stack up? VALUE Project Final Report: Regenerative medicine value systems: Navigating the uncertainties, p55-65. Available at: http://www.biolatris.com/Biolatris/News_&_events_files/VALUE%20Final%20Report.pdf

- McKernan, R. McNeish, J. Smith, D. (2010). Pharma's developing interest in stem cells. Cell Stem Cell 6(6), 517–520. Article Abstract Abstract DOI

- Pearce, K.F. Hildebrandt, M. Greinix, H. Scheding, S. Koehl, U. Worel, N. Apperley, J. Edinger, M. Hauser, A. Mischak-Weissinger, E. et al. (2014). Regulation of advanced therapy medicinal products in Europe and the role of academia. Cytotherapy 16(3), 289–297. Article Abstract Abstract DOI

- Pharmaceutical Research and Manufacturers of America (PhRMA). 2013Medicines in Development Biologics 2013 Report (Washington: PhRMA) Available at: http://www.phrma.org/sites/default/files/pdf/biologics2013.pdf [pmid: 24113428]

- Salmikangas, P. Celis, P. (2011). Current challenges in the development of novel cell-based medicinal products. Regulatory Rapporteur 8(7/8), 4–7.

- U.S FDA. 2001 Title 21 of the Code of Federal Regulations (CFR) Part 1271 Human Cells, Tissues and Cell and Tissue Based Products

- Van Wilder, P. (2012). Advanced therapy medicinal products and exemptions to the Regulation 1394/2007: how confident can we be? An exploratory analysis. Frontiers in Pharmacology 3(12), 1–9. Article Abstract Abstract DOI

- Warren, V. (2013). Understanding regenerative medicine: a commissioner's viewpoint. Regenerative Medicine 8(2), 227–232. Article Abstract Abstract DOI

- Williams, D.J. Thomas, R.J. Hourd, P.C. Chandra, A. Ratcliffe, E. Liu, Y. Archer, J.R. (2012). Precision manufacturing for clinical-quality regenerative medicines. Philosophical Transactions of Royal Society A 370(1973), 3924–3949. Article Abstract Abstract DOI

- Wohn, D.Y. (2012). Korea okays stem cell therapies despite limited peer-reviewed data. Nature Medicine 18, 329. Article Abstract Abstract DOI