The neural crest is a transient embryonic structure in vertebrates that gives rise to most of the peripheral nervous system (PNS) and to several non-neural cell types, including smooth muscle cells of the cardiovascular system, pigment cells in the skin, and craniofacial bones, cartilage, and connective tissue. Although neural crest cells undergo developmental restrictions with time, at least some neural crest cells have the capacity to self-renew and display a developmental potential almost only topped by embryonic stem (ES) cells. Intriguingly, such neural crest-derived stem cells (NCSCs) are not only present in the embryonic neural crest, but also in various neural crest-derived tissues in the fetal and even adult organism. These postmigratory NCSCs functionally resemble their embryonic counterparts in their ability to differentiate into a variety of cell types. Because of their broad potential, the possibility to isolate NCSCs from easily accessible tissue, and the recent accomplishment to generate NCSC-like cells from human ES and induced pluripotent stem (iPS) cells, NCSCs have become an ideal model system to study stem cell biology in development and disease. Despite exciting achievements in the field, several pressing issues remain to be addressed, however, such as the mechanisms regulating expansion and fate decisions in NCSCs from different sources and the still unknown physiological roles of NCSCs in the adult organism.

1. Introduction

The neural crest, a unique transient embryonic cell population, was initially identified by the Swiss embryologist Wilhelm His in 1868, as a group of cells localized in between the neural tube and the epidermis in the vertebrate embryo. Neural crest cells originate in the ectoderm at the margins of the neural tube and, after a phase of epithelial-mesenchymal transition and extensive migration, settle down in different parts of the body to contribute to the formation of a plethora of different tissues and organs. Neural crest derivatives originate from four major segments of the neuraxis: cranial, cardiac, vagal, and trunk neural crest. The cranial neural crest gives rise to the majority of the head connective and skeletal structures, nerves and pigment cells. Cardiac neural crest cells considerably contribute to heart development by forming the aorticopulmonary septum and conotruncal cushions, while enteric ganglia of the gut represent a major derivative of the vagal neural crest. Trunk neural crest cells migrate along two major pathways: Cells migrating along the dorsal pathway populate the skin where they give rise to melanocytes; cells migrating along the lateral pathway generate sensory and sympathetic ganglia and adrenal chromaffin cells, among others (Le Douarin and Dupin, 2003). However, although cell fate acquisition is apparently influenced by intrinsic positional information (Le Douarin et al., 2008; Lwigale et al., 2004; Santagati and Rijli, 2003), neural crest cell populations along the neuraxis share potentials, as shown by in vivo transplantation and mass culture experiments (Le Douarin and Dupin, 2003). For instance, neural crest cells from the trunk are able to produce mesenchymal derivatives when challenged with appropriate extracellular cues (Graham et al., 1996; Shah et al., 1996), underscoring the importance of environmental signals in regulating neural crest development.

2. Embryonic neural crest

2.1. Lineage analysis and fate decisions of NCSCs

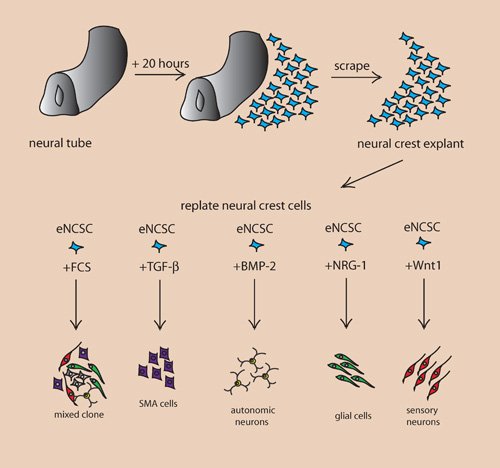

Despite the fact that the neural crest can generate a great variety of cell and tissue types and therefore represents a multipotent cell population, the “stemness” of neural crest cells as individual cells had to be demonstrated on the single cell level. To address the developmental potential of individual neural crest cells in vivo, several studies performed single cell tracing either by retrovirus-mediated gene transfer or dye injection (Bronner-Fraser and Fraser, 1989; Frank and Sanes, 1991). These experiments revealed that in vivo at least some neural crest cells give rise to multiple cell types, including neurons, glia, smooth muscle, and melanocytes. With the establishment of culture systems allowing the analysis of large cell numbers, it became apparent that multipotent cells are relatively frequent among the neural crest cell population (Sommer, 2001). To address their potential in vitro, neural crest cells are cultured as neural tube explants derived from avian or rodent embryos at stages before neural crest cell emigration (see Figure 1). After emigration from the neural tube in culture, neural crest cells represent a relatively pure cell population. When grown in a rich medium containing serum, these cells differentiate into a number of neural crest derivatives. Moreover, in vitro neural crest cells can be propagated at clonal densities allowing the investigation of multipotency of a single neural crest cell. Using such a clonal culture system, it was demonstrated that avian neural crest cells are multipotent (Baroffio et al., 1991; Sieber-Blum and Cohen, 1980). Later, Stemple and Anderson coined the term “NCSC” when showing that rodent neural crest cells in vitro not only have the ability to give rise to autonomic neurons, glia, and smooth muscle, but also to self-renew, a unique characteristic of stem cells (Stemple and Anderson, 1992). Subsequently, NCSCs comprised in early stage emigrating trunk neural crest have been identified (Lee et al., 2004). In defined culture conditions, these cells display an even greater potential than previously described NCSCs, having the capacity to also generate sensory neurons at clonal density. Finally, Dupin and colleagues have recently demonstrated the existence of a highly multipotent cell predominantly found in cephalic neural crest and able to produce clones comprising cell types as diverse as neurons, glia, melanocytes, chondrocytes, osteoblasts, and smooth muscle (Calloni et al., 2009).

Figure 1. Instructive growth factors regulating fate decisions in embryonic NCSCs.

Schematic depiction of an in vitro culture system used to isolate NCSCs. The neural tube is isolated from a rodent or avian embryo at a developmental stage before in vivo neural crest cell delamination. After plating the neural tube onto a substrate-coated plastic dish, NCSCs emigrate from the dorsal part of the neural tube to form a so-called neural crest explant. Subsequently, these cells can be trypsinized and plated as single cells at clonal density in a media supplemented with specific growth factors. In such an in vitro system, addition of fetal calf serum and/or chicken embryo extract results in mixed clones composed of several neural crest-derived lineages. In contrast, addition of instructive growth factors leads to the generation of specific lineages at the expense of other possible fates. For instance, TGF-β promotes a non-neural fate when added to a single NCSC. BMP2 promotes autonomic neurogenesis by upregulating the expression of the basic helix-loop-helix (bHLH) transcription factor Mash-1. NRG isoforms promote gliogenesis, while –at least in the mouse– canonical Wnt signaling induces sensory neurogenesis. Instructive growth factors for other fates, such as melanocytes and chondrocytes, have not been identified to date.

In addition to demonstrating the stem cell nature of a considerable fraction of neural crest cells, in vitro studies also revealed environmental signals regulating fate decisions in NCSCs (reviewed in Le Douarin et al., 2004; Sieber-Blum, 1998; Sommer, 2006). In principle, two possible modes of action have been proposed for such factors: a specific factor could selectively favor the development of a given lineage or, alternatively, a factor could “instruct” a NCSC to adopt a certain fate at the expense of all other possible fates. The first group of growth factors includes, for instance, sonic hedgehog (Shh) that favors the development of neural crest progenitors with both mesenchymal skeletogenic and neural potentials as opposed to progenitors with neural potentials only (Calloni et al., 2007; Calloni et al., 2009). In addition, Shh promotes chondrogenic differentiation. Stem cell factor (SCF) is known to act as a survival factor for NCSCs and in combination with nerve growth factor (NGF), brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF), and neurotrophin 3 (NT-3) is trophic for the melanocytic lineage (Langtimm-Sedlak et al., 1996; Sieber-Blum, 1998). Similarly, endothelin 3 (ET3) promotes proliferation and survival of melanocytic and glial progenitors (Lahav et al., 1998; Le Douarin et al., 2004), while basic fibroblast growth factor (FGF2) acts as a mitogen for multipotent NCSCs (Zhang et al., 1997).

The availability of clonal cell cultures also made it possible to identify several growth factors acting instructively on migratory NCSCs. For instance, dependent on the context, members of the transforming growth factor (TGFβ) family either promote the generation of smooth muscle cells, autonomic neurogenesis, or apoptosis (Hagedorn et al., 1999; Shah et al., 1996). Consistent with these findings, conditional ablation of TGFβ signaling in neural crest cells in vivo leads to heart defects associated with loss or impaired development of smooth muscle cells, in addition to malformations of the anterior eye, cranial bones and cartilage (Ito et al., 2003; Ittner et al., 2005; Wurdak et al., 2005). Surprisingly, however, conditional ablation of Smad4, an intracellular effector molecule of canonical TGFβ signaling pathway, does not alter smooth muscle or neuronal fate acquisition by neural crest cells, pointing at an involvement of alternative signaling pathways (Buchmann-Moller et al., 2009). Wnt (wingless in Drosophila) acting via the intracellular molecule β-catenin represents a good example of an instructive growth factor, for which cell culture data turned out to be highly relevant in vivo: Wnt/β-catenin signal activation instructs NCSCs to adopt a sensory neuronal fate in vitro, promotes the sensory lineage at the expense of all other neural crest cell fates in vivo, and is required for sensory neurogenesis in vitro and in vivo (Hari et al., 2002; Lee et al., 2004). Wnt/β-catenin inactivation in mouse neural crest also leads to loss of melanocytes (Hari et al., 2002), and Wnts promote melanocyte formation in Zebrafish (Dorsky et al., 1998; Dunn et al., 2000), but an instructive role of Wnt/β-catenin in melanocyte formation has not been reported. Thus, putative instructive growth factors for melanocytes as well as for many other neural crest-derived lineages still remain to be identified.

2.2. Maintenance of multipotency in NCSCs

ES cells – the stem cell prototype – are immortal and can be propagated by symmetrical division for an unlimited amount of time in vitro. For several years, researchers attempted to identify signals supporting the self-renewal of NCSCs in a similar manner. Intriguingly, rather than by a single factor, maintenance of an undifferentiated state of early NCSCs was achieved by the simultaneous activation of Wnt and bone morphogenic protein (BMP) signaling pathways in vitro (Kleber et al., 2005). Combinatorial Wnt/BMP supported persistent expression of the NCSC markers p75NTR (a low affinity neurotrophin receptor) (Stemple and Anderson, 1992) and of Sox10 (a high mobility group transcription factor) (Paratore et al., 2001) and maintained multipotency, while at the same time inhibiting the differentiation process. However, the molecular mechanisms leading to Wnt/BMP-mediated self-renewal are still puzzling. One of the downstream targets of Wnt/BMP signaling could be Sox10. The spontaneous mouse mutant Dominant megacolon, expressing a mutant form of Sox10, and mice carrying a targeted Sox10 null mutation display multiple neural crest defects, including absence of enteric, sympathetic, and parasympathetic ganglia, and loss of glia, melanocytes, and adrenal chromaffin cells (Britsch et al., 2001; Herbarth et al., 1998; Kapur, 1999). Moreover, Sox10 maintains NC stem cell multipotency in vitro by inhibiting both neuronal and smooth muscle differentiation (Kim et al., 2003) and regulates fate decisions in multipotent NCSCs in vitro and in vivo (Paratore et al., 2002; Paratore et al., 2001).

Recently, Nikopoulos and colleagues showed that attenuated Notch signaling by application of a soluble Notch ligand, Jagged1, to neural crest cells leads to their continuous self-renewal over several generations in vitro (Nikopoulos et al., 2007). Thereby, complemetary autocrine FGF signaling contributes to Notch-mediated maintenance of NCSCs. Another study demonstrated that the transcriptional repressor of the winged helix or forkhead family Foxd3 is necessary to maintain a neural crest population in vivo (Teng et al., 2008). Using Wnt1-Cre transgenic mice to achieve ablation of Foxd3 specifically in the neural crest population, Teng and colleagues demonstrated that in the absence of the endogenous Foxd3 gene the neural crest population is severely impaired, resulting in a dramatic loss of most neural crest derivatives. Interestingly, Sox10 is one of the genes substantially downregulated in Foxd3 mutant embryos (Teng et al., 2008). Moreover, overexpression of Foxd3 in the neural tube of chicken embryos leads to upregulation of HNK-1 and Cad-7, markers of migratory neural crest (Dottori et al., 2001).

2.3. Alternative sources of neural crest cells: ES- and iPS-cell based strategies

Since only a limited number of cells can be obtained from an embryo, most biochemical and related studies are difficult, if not impossible, to perform with directly isolated NCSCs. Therefore, despite recent achievements to expand primary NCSCs in culture, finding alternative neural crest sources has been the focus of many laboratories. In particular, an increasing number of reports have illustrated the derivation of neural crest and/or neural crest derivatives from mouse and human ES cells (Billon et al., 2007; Hotta et al., 2009; Mizuseki et al., 2003; Motohashi et al., 2007; Pomp et al., 2008). Most of these studies have failed, however, to obtain long-term cell cultures resembling endogenous neural crest cells.

Studer and colleagues recently described the derivation of multipotent neural crest cells from human ES cells using the power of neural rosette cultures, in which neural induction is achieved by co-culture with the MS5 stromal line (Lee et al., 2007). This study has implemented the prospective identification of neural crest-like cells based on p75NTR expression, followed by subsequent clonal analysis. When induced with FGF2 and BMP2 growth factors, human ES cells generated a high number of p75NTR-expressing cells that were multipotent and gave rise to neurons, glia, and myofibroblasts. Importantly, using mesenchymal stem cell differentiation protocols, Lee et al. showed that these cells are also able to give rise to adipocyte, chondrocyte, and osteoblast lineages. Finally, the addition of FGF2 and EGF allowed prolonged propagation of p75NTR-positive cells in culture. Similar to this study, Lawlor and colleagues also achieved the derivation of multipotent neural crest-like cells from human ES cells (Jiang et al., 2009). These authors co-cultured ES cells with the PA6 cell line followed by fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) of p75NTR-expressing cells that were capable of generating neurons, glia, and smooth muscle actin (SMA)-expressing cells. It remains to be investigated whether these protocols could be applied as such to mouse ES cells. However, the possibility to produce human cells with NCSC features offers an exciting strategy for modeling human disease. Indeed, the Studer group has recently applied its protocol to iPS cells derived from human patients suffering from familial dysautonomia, a disease characterized by the depletion of autonomic and sensory neurons (Lee et al., 2009). Using this system, defects in neurogenesis and migration of patient-specific neural crest precursors were revealed that were treatable in culture with appropriate drugs. Thus, the iPS cell technology is suitable to provide new insights into pathogenesis and potential treatment of human neurocristopathies.

3. Postmigratory NCSCs

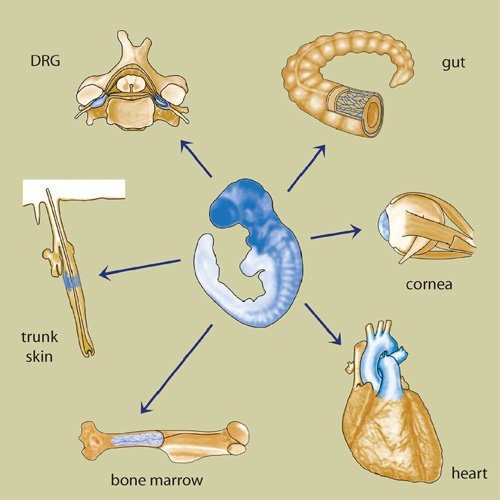

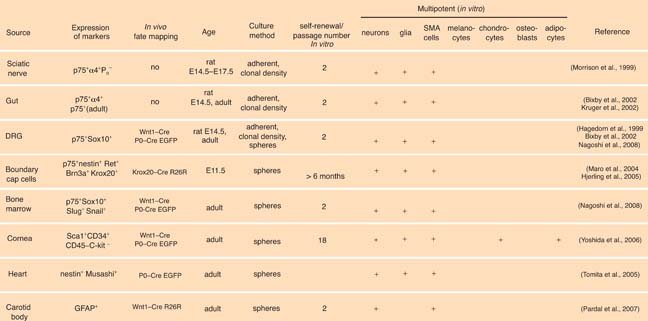

As the neural crest represents a transitory embryonic cell population, it has been assumed that NCSCs represent “in vitro stem cells” similar to ES cells isolated from the blastomere, displaying stem cell features in culture, but only transiently found in the living organism. The discovery of NCSC-like cells in postmigratory targets of embryonic neural crest, such as the sciatic nerve, dorsal root ganglia (DRG), the gut, and the skin was therefore surprising (Delfino-Machin et al., 2007) (see Table 1; Figure 2). A major breakthrough in the field came with the demonstration that even the adult organism contains multipotent, self-renewing populations of neural crest-derived cells with a developmental potential resembling that of embryonic NCSCs (Kruger et al., 2002). However, although they are able to generate neuronal, glial, and non-neural cell types, postmigratory NCSCs from different regions as well as NCSCs isolated at different time points display cell-intrinsic differences in response to microenvironmental factors (Bixby et al., 2002; Wong et al., 2006). The mechanisms underlying these intrinsic changes are ill defined, but can involve changes in growth factor receptor expression levels (White et al., 2001). Moreover, we showed that NCSCs undergo stage-dependent transitions with respect to their growth requirements: As mentioned above, self-renewal of early migratory NCSCs is controlled by combinatorial Wnt and BMP signaling (Kleber et al., 2005). In contrast, later stage postmigratory NCSCs loose Wnt responsiveness and acquire responsiveness to mitogenic EGF acting upstream of the small Rho GTPases Cdc42 and Rac1 (Fuchs et al., 2009). Accordingly, deletion of either Cdc42 or Rac1 in NCSCs results in size reduction of virtually all neural crest-derived structures. Thus, although endowed with similar potentials, NCSCs exhibit intrinsic properties characteristic for their spatiotemporal context. This presumably allows NCSCs to adapt to their local environment, producing appropriate numbers of specific cell types at the right time and location (Falk and Sommer, 2009).

Figure 2. Postmigratory NCSCs.

In the adult organism, several different tissues contain cells with a self-renewal capacity and differentiation potential resembling those of neural crest cells during embryonic development. NCSCs have been described in DRG, gut, cornea, heart, bone marrow, and skin. In the gut, NCSCs have been associated with the submucosal plexus, myenteric plexus, and the outer muscle layer. In the cornea, neural crest-derived cells with stem cell features are thought to be located in the corneal stroma and epithelium. In the heart, NCSCs appear to be concentrated at the outflow tract and at the intramuscular and subepicardial layers of ventricles, as well as within the atrial wall. In the bone marrow, NCSCs are tightly associated with the bone marrow surface. In the trunk skin, NCSCs are located in the bulge region of the hair follicle and are associated with nerve endings surrounding the hair follicle.

3.1. Sciatic nerve and gut

In 1999, Morrison described the isolation of postmigratory NCSCs from rat E14.5 sciatic nerve by flow cytometry using the antibodies against p75NTR and P0, a peripheral myelin protein (Morrison et al., 1999). The fraction of p75NTR+/P0− cells showed a self-renewal potential in vivo as assessed by BrdU incorporation experiments and generated neurons and glia upon transplantation into chick embryos. Moreover, these cells were functionally indistinguishable from in vitro NCSCs isolated from explant cultures when challenged with instructive growth factors, since the addition of BMP2 and neuregulin (NRG1) resulted in generation of neurons and glial cells, respectively. In vivo, fetal sciatic nerve NCSCs are at least bipotent and give rise to glia and nerve fibroblasts, as revealed by genetic fate mapping in the mouse (Joseph et al., 2004). However, upon transplantation into chick embryos, NCSCs isolated from sciatic nerve failed to generate sensory neurons in vivo, while they generated neurons in autonomic ganglia (White et al., 2001).

The existence of cells with self-renewing potential was also demonstrated for rat E14.5 DRG, sympathetic ganglia, and – using α4-integrin as an additional cell surface marker in combination with p75 – for the enteric nervous system (Bixby et al., 2002). Strikingly, when comparing the developmental potential of NCSCs from sciatic nerve and gut, sciatic nerve cells mainly generated glia when transplanted, while NCSCs from the gut gave preferentially rise to neurons. Moreover, sciatic nerve NCSCs failed to migrate into the gut even when transplanted into the gut wall, demonstrating intrinsic differences between fetal sciatic nerve and gut NCSCs in terms of their migratory capacity and developmental potential (Mosher et al., 2007).

Similar to gut and sciatic nerve fetal NCSCs, a p75NTR-positive cell fraction from adult gut is enriched for multipotent cells, but in contrast to fetal NCSCs, adult NCSCs are negative for α4-integrin (Kruger et al., 2002). Importantly, the self-renewal degree of NCSCs decreases with age and, based on BrdU incorporation rate, adult NCSCs appear to be less mitotically active as compared to fetal NCSCs. Additionally, the developmental and differentiation potential of adult gut NCSCs differs substantially from the one of fetal NCSCs. Postnatal gut NCSCs appear to be more sensitive to gliogenic and less responsive to neurogenic cues than embryonic gut NCSCs. Consistent with the limited neuronal potential in vitro, adult gut NCSCs gave only rise to a small number of neurons in vivo when transplanted into chick embryos.

Although the mature ENS had been shown to retain stem cells, the role of these cells remained obscure until recently, when the Gershon laboratory provided evidence for enteric neurogenesis in adult mice (Liu et al., 2009). This study revealed an unexpected degree of plasticity in the ENS and showed that postnatal neurogenesis in the gut can be stimulated by serotonin (5-HT). Moreover, the 5-HT4 receptor is required postnatally for ENS growth and maintenance. These findings raise the intriguing possibility that 5-HT4 agonists could be used to promote enteric neuronal survival and/or neurogenesis in human subjects with ENS disorders.

3.2. DRG

The first observation that DRG contain cells with greater potential than normally observed during embryonic development came from transplantation experiments carried out in birds (Ayer-Le Lievre and Le Douarin, 1982; Schweizer et al., 1983). Later, Hagedorn and colleagues reported the isolation of multipotent progenitor cells from early (E14-E16) rat DRG that are able to generate clones containing neurons, glia, and SMA-positive cells (Hagedorn et al., 1999). However, the self-renewal capacity of these cells was not tested. Another study reported the isolation of multipotent cells that were propagated in sphere cultures for more than 6 months from E11.5 mouse DRG (Hjerling-Leffler et al., 2005). These cells originated from so-called boundary cap (BC) cells, a PNS cell type of neural crest origin (Maro et al., 2004). A couple of recent reports described that neural crest-derived precursor cells also exist in the adult DRG (Li et al., 2007; Nagoshi et al., 2008). Using explant cultures, Li et al. provided evidence that in the adult rat DRG a subpopulation of cells double-positive for nestin and p75NTR displays multipotency and sphere-forming potential. However, their limited self-renewal potential might point to a restricted progenitor rather than stem cell status of these cells. To address the nature of these progenitor cells, the authors performed DRG axotomy combined with BrdU labeling and observed that all neurons were BrdU-negative, whereas most BrdU-positive cells were found surrounding neurons, suggesting an association of DRG-derived progenitors with the glial lineage. Similar cells have also been isolated from mouse DRG at various postnatal stages taking advantage of mouse genetic approaches (Nagoshi et al., 2008). Okano and colleagues used P0-Cre/CAG-CAT-EGFP (herein after referred to as “FloxedEGFP”) and Wnt1-Cre/FloxedEGFP transgenic mice to prospectively identify and directly isolate neural crest-derived stem/progenitor cells. EGFP-expressing cells isolated by flow cytometry showed a strong expression of the NCSC markers p75NTR and Sox10 and, upon differentiation, gave rise to neurons, glia, and smooth muscle cells (Nagoshi et al., 2008). The extent of the self-renewal capacity of NCSC-like cells in the adult DRG, as well as their physiological role, remains to be addressed. It seems likely, though, that such cells might be involved in injury-induced de novo neurogenesis, as observed upon capsaicin-mediated destruction of neurons in rat nodose ganglia (Czaja et al., 2008).

3.3. Bone marrow

Bone marrow stromal cells (BMSCs) were shown to differentiate into osteoblasts, chondrocytes, adipocytes, and myoblasts (reviewed in (Prockop, 1997). Surprisingly, there have been a number of reports describing that BMSCs can also generate neurons and glia in vitro and even after transplantation into the central nervous system (Arnhold et al., 2006; Azizi et al., 1998; Hofstetter et al., 2002; Sanchez-Ramos et al., 2000; Woodbury et al., 2000). The identity of the cell population with the ability to generate neural cells remained unclear, and some researchers favored the idea that neurons might derive from bone marrow cells by transdifferentiation. Intriguingly, the reported differentiation potential of BMSCs is strikingly similar to the one of NCSCs. This raised the question of whether the neural potential of BMSCs could be explained by the presence of a neural crest-derived cell subpopulation in bone marrow. Indeed, while mesenchymal stem cells have been generally assumed to be of mesodermal or even endodermal orgin (Ogawa et al., 2006), a first wave of mesenchymal stem cells in the embryo actually derive from neural crest (Takashima et al., 2007). Recently, compelling evidence for the existence of NCSCs (i.e. cells with mesenchymal as well as neural potential) in bone marrow emerged from a study by Nagoshi et al. (Nagoshi et al., 2008). Utilizing Wnt1-Cre/FloxedEGFP mice for in vivo fate mapping, these researchers isolated neural crest-derived cells from the bone marrow that could be propagated in sphere cultures for a couple of passages. While most of these spheres comprised developmentally restricted cells producing myofibroblasts, a bit more than 3% of the isolated bone marrow cells had the capacity to generate neurons, glia, and smooth muscle cells upon differentiation. Collagenase treatment increased the number of obtainable EGFP-positive cells, suggesting a tight association of neural crest-derived cells with the bone marrow surface. Thus, the bone marrow appears to contain several distinct stem cell types of different developmental origins. Although their frequency drastically decreases with age, multipotent NCSCs in the adult bone marrow could provide an attractive source for future cell replacement therapies of the nervous system, given that bone marrow can easily be harvested from patients.

3.4. Cornea

During development, neural crest cells migrate to the developing eye and give rise to a large part of the anterior eye segment as shown by transplantation experiments in birds and by in vivo fate mapping in transgenic mice (Gage et al., 2005; Ittner et al., 2005; Johnston et al., 1979). Yoshida and colleagues reported that neural crest-derived cells isolated from adult mouse cornea express the neural crest markers Twist, Snail, Slug and Sox9 and have the potential to differentiate into neurons, adipocytes, and chondrocytes (Yoshida et al., 2006). In contrast, Brandl et al. were able to establish a neural crest-derived cell line with adipogenic, osteogenic, chondrogenic, and neuronal potential only from neonatal, but not adult mouse cornea (Brandl et al., 2009). Possibly, the discrepancy between the two studies could be due to differential contribution of anterior eye structures to the cell preparations analyzed. Indeed, neural crest cells generate a variety of very distinct eye structures, including corneal stromal keratocytes, corneal endothelium, and the ciliary body. Therefore, it will be important to determine the exact stem cell niche in order to better characterize nature and role of putative NCSCs in the anterior eye.

3.5. Heart

In the embryo, cardiac neural crest cells participate in the aorticopulmonary septation, and the ablation of cardiac neural crest results in cardiac outflow defects (Kirby et al., 1983). Intriguingly, several reports have described the isolation of neural crest-like cells from neonatal and adult heart (El-Helou et al., 2008; Tomita et al., 2005). These cells express the neural stem cell markers nestin and musashi-1, have sphere-forming potential and are located among cardiac myocytes throughout the ventricle and aorta of the rat heart. Lineage tracing experiments using Wnt1-Cre/Z/EG and PO-Cre/FloxedEGFP mice demonstrated that nestin-positive cells express EGFP and therefore are of neural crest origin (El-Helou et al., 2008; Tomita et al., 2005). Upon in vitro differentiation cardiosphere-derived cells gave rise to neurons, glial, and smooth muscle cells and when transplanted into chicken embryos migrated to the cardiac outflow tract as well as to DRG, sympathetic ganglia, and spinal nerves (Tomita et al., 2005). Interestingly, infarct regions of rat and human hearts also contain nestin-expressing cells with sphere-forming activity, and the transplantation of fluorescently labeled nestin-positive cells into infarct regions resulted in their contribution to reparative fibrosis in the injured area (El-Helou et al., 2008).

3.6. Carotid body

The carotid body (CB) is an oxygen-sensing organ of the sympathoadrenal lineage that was reported to contain cells of neural crest origin (Pearse et al., 1973). Pardal and colleagues described that under low-oxygen conditions, a stem cell population of the CB proliferates and gives rise to new dopaminergic neurons in vivo and in vitro (Pardal et al., 2007). Strikingly, cell fate mapping experiments using a Wnt1-Cre reporter line demonstrated that the CB stem cells are neural crest-derived glia-like cells with sphere-forming capacity and the potential to produce TH-positive neurons and smooth muscle cells in vitro. Upon activation in vivo, these stem cells seem to downregulate the glial marker GFAP to become nestin-positive, proliferative intermediate progenitors contributing to de novo neurogenesis. The presence of GFAP-positive stem cells in a germinal niche is reminiscent of neural stem cells in the adult CNS subventricular zone (SVZ). Unlike the SVZ, however, the CB germinal zone is apparently not permanently active. Rather, on return to normoxia, proliferation and differentiation of intermediate progenitors cease, followed by re-acquisition of a quiescent GFAP-positive stem cell phenotype. These results are highly relevant, because they point to a physiological role of NCSCs in the adult organism. In addition, because of the dopaminergic nature of CB-derived neurons, CB stem cells could potentially be applied in future cell replacement therapies in Parkinson's disease.

3.7. Dental pulp and periodontal ligament

Dental pulp and periodontal ligament are tissues originating from cranial neural crest. Several groups have reported the isolation of a cell population from postnatal dental pulp tissue that exhibited clonogenic capacity and were therefore named dental pulp stem cells (DPSCs) (Coura et al., 2008; Gronthos et al., 2002; Gronthos et al., 2000; Stevens et al., 2008; Iohara et al., 2006; Yang et al., 2007b; Yang et al., 2007a). In vivo, when transplanted into immunocompromised mice, DPSCs generated dentin-like structures (Gronthos et al., 2002; Gronthos et al., 2000) and when injected into the avian embryo DPSCs migrated into facial structures and gave rise to neurons (Arthur et al., 2008). In vitro DPSCs generated adipocytes and differentiated into functionally active neurons, as assessed by electrophysiological analysis (Arthur et al., 2008; Gronthos et al., 2002). Moreover, Stevens and colleagues demonstrated that human DPSCs have the ability to differentiate into chondrocytes and melanocytes in vitro (Stevens et al., 2008). In addition to the sphere-forming capacity, DPSCs appeared to be label retaining cells (Stevens et al., 2008). Moreover, Iohara and colleagues reported the isolation of a multipotent and self-renewing population of cells from porcine dental pulp that could be differentiated into odontoblasts upon addition of BMP2 (Iohara et al., 2006). Like dental pulp, periodontal ligament tissue derives from the neural crest and also appeares to contain cells with NCSC properties at postnatal stages (Coura et al., 2008). In vitro, these cells expressed markers of neural crest cells such as HNK-1 and p75NTR, and were able to generate adipocytes, osteoblasts, and myofibroblasts.

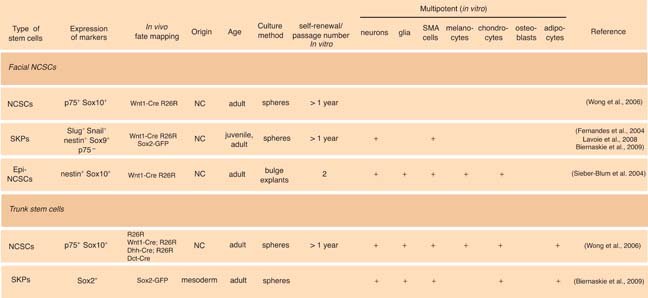

Table 1. Postmigratory neural crest derived stem cells

Table 1.

Postmigratory neural crest derived stem cells

4. NCSCs and other cells with neural potential in the skin

The discovery of multipotent stem cells in the skin was perhaps one of the most intriguing and therapeutically significant findings of the last few years in the field of adult NCSCs. The skin is beyond any doubt the most accessible tissue of the body for autologous cell replacement therapies and regenerative medicine. Several laboratories have independently described the isolation of multipotent cells with stem cell properties that have the potential to generate neurons, glia, myofibroblasts, chondrocytes, adipocytes, and melanocytes from human, pig, and rodent skin (Belicchi et al., 2004; Dyce et al., 2004; Fernandes et al., 2004; Sieber-Blum et al., 2004; Toma et al., 2001; Wong et al., 2006; Amoh et al., 2005; Joannides et al., 2004; Shih et al., 2005; Sieber-Blum et al., 2004; Toma et al., 2005). For instance, multipotent skin-derived cells have been enriched by means of their sphere-forming capacity (Toma et al., 2001) or based on markers found on hematopoietic stem cells (Belicchi et al., 2004), or have been isolated from transgenic animals expressing GFP from promoter elements of nestin (Amoh et al., 2005). Nestin is expressed in neural progenitor cells, but in the skin is also found in postmitotic non-neural structures of the hair follicle such as the outer root sheath (Li et al., 2003). Although revealing cells with an unexpected potential in the skin, these studies did not address the nature and origin of the multipotent cells analyzed. Such an analysis is important, though, as fate and in vivo potential of stem cells are likely dependent on their origin and exact localization. In particular, the skin contains a great stem cell repertoire, including epidermal stem cells, melanocyte stem cells, and mesenchymal stem cells. Moreover, mesenchymal components of facial and trunk skin are of distinct developmental origins, derived from neural crest and the mesoderm, respectively. The field was substantially boosted, therefore, when genetic tools in the mouse were introduced to trace multipotent cells in the skin and to define their niches in vivo. These studies demonstrated multiple origins of multipotent skin cells. In the facial skin, they include the hair follicle bulge, the dermal papilla, and other neural crest-derived mesenchymal structures (Fernandes et al., 2004; Sieber-Blum et al., 2004; Wong et al., 2006). In the trunk skin, they comprise mesoderm-derived dermal papilla (Biernaskie et al., 2009) as well as glial and melanocytic components in the hair follicle bulge (Wong et al., 2006). Below we discuss the findings by several laboratories and summarize the differences and similarities between recently described populations of multipotent stem cells in the skin.

4.1. Multiple origins of NCSCs in the facial skin

In 2001, Miller and colleagues reported the isolation of self-renewing, multipotent cells from the skin of rodents and humans and named these stem cells skin-derived precursor (SKP) cells (Toma et al., 2001). Initially, the nature of SKPs was unclear. However, their differentiation potential suggested a neural crest origin, since SKPs could generate neurons, glia, smooth muscle cells, and adipocytes. In a follow-up publication, the same research group illustrated that SKPs display properties similar to embryonic NCSCs (Fernandes et al., 2004). In particular, SKPs were shown to express neural crest markers, such as Slug, Snail, Twist, Pax3, and Sox9. The developmental potential of SKPs was tested upon transplantation into chick embryo. Interestingly, when EYFP-labeled SKPs were injected into the neural crest migratory stream, some SKPs migrated to DRG, peripheral nerves and, importantly, the dermal layer of the skin. Taking advantage of Wnt1-Cre/R26R mice to trace the neural crest lineage, Fernandes et al. demonstrated that almost all whisker papilla cells, as well as many dermal cells were β-galactosidase positive, indicating that hair follicle papilla as well as SKPs are of neural crest origin and that the hair follicle papilla represents the endogenous niche for SKPs in facial skin.

Using a different culture condition, the group of Sieber-Blum described the presence of multipotent cells in the adult hair follicle called epidermal neural crest cells (EPI-NCSCs) (Sieber-Blum et al., 2004). Unlike SKPs, EPI-NCSCs are localized to the bulge region of whisker follicles, as demonstrated by microdissection (Sieber-Blum et al., 2004). Similar to the studies by Miller and co-workers, Wnt1-Cre/R26R mice were used for lineage tracing of neural crest cells in whisker follicles. Interestingly, Sieber-Blum observed β-galactosidase-positive streams of cells within the hair follicle, indicative for neural crest-derived cells migrating from the bulge region to the hair matrix. Using an elegant bulge explant culture system, numerous β-galactosidase-positive cells were shown to disperse from the bulge of the whisker follicle and to express Sox10, comparable to embryonic NCSCs in neural tube explant cultures. When subjected to an in vitro clonal analysis, EPI-NCSCs gave rise to neurons, glia, smooth muscle cells, and melanocytes. Moreover, when differentiated in the presence of NRG1. EPI-NCSCs generated Schwann cell progenitors and neurons. However, in contrast to embryonic NCSCs, addition of BMP-2 to clonal cultures of EPI-NCSCs resulted in the generation of adipocytes.

Thus, multipotent cells of neural crest origin can be traced back to distinct structures in the facial skin (see Table 2; Figure 3). As an extension of these results, we have found that apart from the bulge and the dermal papilla, the capsula and the dermal sheath of the whisker follicle of Wnt1-Cre/R26R mice also contain β-galactosidase positive cells that display sphere-forming capacity upon microdissection (Wong et al., 2006). Similarly, the ringwulst of rat whisker follicles (too small to be dissected from mouse follicles) harbors sphere-forming cells. It remains to be shown whether the various facial skin structures from which NCSC-like cells have been isolated indeed contain actual stem cell niches, fulfilling hitherto unknown physiological functions, or whether neural crest-derivatives can acquire stem cell features in culture by de-differentiation.

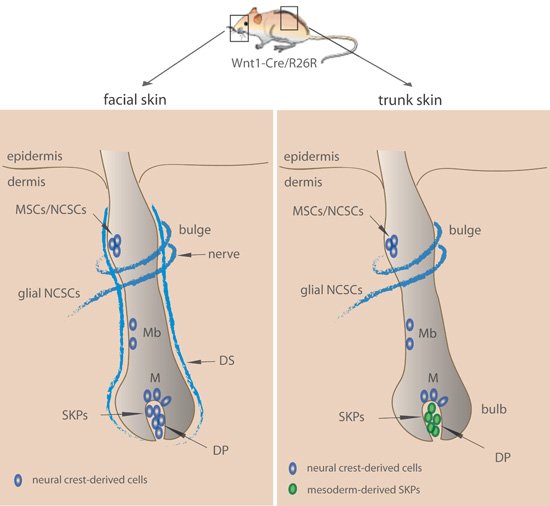

Figure 3. Location of multipotent stem cells with neurogenic potential in facial and trunk skin.

In the facial skin (left panel), neural crest-derived structures (shown in blue) harbor NCSCs located in the bulge, dermal sheath (DS), and dermal papilla (DP). NCSCs associated with the glial lineage are associated with nerve endings. Melanocyte stem cells in the bulge (MSCs), melanoblasts (Mb), and melanocytes (M) are as well of neural crest origin. In the facial skin, skin-derived precursors (SKPs) located in the dermal papilla originate from the neural crest. Moreover, note that other structures such as the capsula and ringwulst (not labeled in the scheme) contain neural crest-derived cells with sphere-forming potential.

In the trunk skin (right panel), NCSCs are found both in the bulge containing MSCs and associated with nerve endings. Melanoblasts (Mb) and melanocytes (M) are of neural crest origin as well. Note that dermal papilla (DP) does not derive from the neural crest in the trunk skin. SKPs (shown in green) reside in the DP and can be isolated by means of their GFP expression in Sox2-GFP mice.

4.2. NCSCs and other multipotent stem cells in the trunk skin

Similar to facial skin, skin from the trunk has also been reported to contain spherogenic cells exhibiting both neural and non-neural potentials (Toma et al., 2001; Wong et al., 2006). In the pioneering study by the Miller group (Toma et al., 2001), SKPs from juvenile and adult mouse trunk skin were shown to self-renew extensively in culture and, upon differentiation, to generate cell types as diverse as neurons, glia, smooth muscle, and adipocytes. Strikingly, SKPs were reported to be negative for the NCSC marker p75NTR, while skin-derived spheres described by Wong and colleagues express both p75NTR and Sox10 to a high extend. In the latter study, genetic lineage tracing in the mouse confirmed that a large fraction of skin-derived spheres are of neural crest origin, in agreement with their p75NTR/Sox10 expression (Wong et al., 2006). Such spheres can be extensively passaged and subsequently differentiated into various neural crest derivatives at high and clonal cell density, revealing NCSC properties of cells present in the adult skin.

The combined data (Toma et al., 2001; Wong et al., 2006) are consistent with the idea that the trunk skin harbors different types of spherogenic cells, which might be preferentially selected or enriched for depending on the protocol used. This raises the question of the nature and origins of multipotent stem cells found in the trunk skin. Unlike in the head, the mesenchyme in the trunk is not derived from the neural crest. Consistent with this, β-galactosidase expression in back skin of two distinct reporter lines for neural crest lineages, Wnt1-Cre /R26R and Ht-PA-Cre/R26R mice, was only observed in nerves, in the hair follicle bulge region containing nerve endings and melanocyte stem cells, and in the bulb of hair follicles where mature melanocytes are located (Wong et al., 2006). Furthermore, some β-galactosidase-positive cells in the bulge region of the back skin of Wnt1-Cre/R26R and Ht-PA-Cre/R26R mice co-express the NCSC markers p75NTR and Sox10in vivo. In contrast, other follicular structures that in the face are of neural crest origin and spherogenic –as in particular the dermal papilla– do not comprise β-galactosidase-expressing cells and lack Sox10 expression in the trunk in vivo (Wong et al., 2006). Thus, by definition, NCSC niches in the trunk must be confined to nerves and/or locations containing melanocytic cells (see Figure 3).

4.2.1. Melanocyte stem cells and NCSCs of the melanocytic and glial lineage

During development, melanocytes emerge from a subpopulation of neural crest cells and migrate along a dorsolateral pathway to colonize their final target – skin. Around embryonic day thirteen, melanoblasts populate the skin epidermis and settle down in the hair follicles. In the skin, melanocyte survival is strongly dependent on the cycling nature of the hair follicle. Each hair follicle undergoes degeneration/regeneration cycles composed of anagen (growth phase), followed by catagen (regression) and telogen (rest phase), and with every cycle new melanocytes localize to the bulb of the hair follicle. The group of Nishikawa was the first to report that continuous melanocyte production is dependent on the activity of self-renewing cells dubbed melanocyte stem cells (Nishimura et al., 2002). MSCs have been extensively studied and are the focus of a separate StemBook chapter (Osawa, 2009).

It is unclear whether melanocyte stem cells represent actual NCSCs, as their full developmental potential has not yet been addressed in vitro or in vivo. However, elegant experiments established that melanocyte stem cells localize to the bulge region of the hair follicle and can be activated to self-renew and to generate melanocytes in vivo (Nishimura et al., 2002). In this study, the authors used a genetic mouse model that allowed labeling of the melanocyte lineage by the expression of β-galactosidase under the control of the Dct promoter (Dct codes for the enzyme dopachrome tautomerase, also referred to as Trp2). β-galactosidase-positive bulge cells were described as small, oval shaped and lacking melanin pigment, suggestive for their undifferentiated status. Moreover, β-galactosidase-positive cells in this mouse model appear to be label-retaining cells since even after 70 days of in vivo BrdU labeling, their nuclei still retained the label. To functionally assess the capacity of melanocyte stem cells to generate melanocytes, a hair reconstitution assay with whisker hair follicles was performed. When whisker hair follicles were dissected into three segments (upper permanent portion, lower permanent portion, and the bulb) and implanted into the skin of albino neonatal mice, only the lower permanent portion (the bulge) gave rise to pigmented hairs. Taken together, these data suggest that melanocyte stem cells in the bulge region of the hair follicle are immature, slow-cycling, self-renewing cells that can generate new melanocytes. Accordingly, several studies have provided compelling evidence that defects in melanocyte stem cells maintenance lead to hair graying (Moriyama et al., 2006; Nishimura et al., 2005; Schouwey et al., 2007).

Intriguingly, though, while melanocyte stem cells express markers of early melanoblasts, such as Dct and Pax3, they have been reported to display no or only low levels of Sox10 (Osawa et al., 2005). This is surprising, as Sox10 is present in at least some Dct-expressing bulge cells (Wong et al., 2006) and also marks committed melanoblasts in or on the way to the bulb. Possibly, Sox10 is transiently downregulated when cells acquire a quiescent state, although this remains to be shown. Since Sox10 regulates multipotency in NCSCs (Kim et al., 2003; Paratore et al., 2002), the data also suggest that melanocyte stem cells lack multipotency. Therefore, one could hypothesize that melanocyte stem cells represent unifated progeny of Sox10-positive NCSCs in the bulge. This does not exclude the possibility that melanocyte stem cells could re-acquire multipotency upon isolation given that a) cells from the melanocyte lineage in the adult skin display sphere-forming capacity, as shown by prospective identification and direct isolation of EYFP-positive cells from Dct-Cre/R26R-EYFP mice (Wong et al., 2006); and b) even when pigmented, melanocytes show an unexpected developmental plasticity and are able to de-differentiate, to self-renew, and to efficiently produce other neural crest lineages such as glia (Dupin et al., 2000).

As in the carotid body, glia-like cells might represent an alternative source for NCSCs in the adult trunk skin. To elucidate whether sphere-forming potential and p75NTR/Sox10 expression are associated with the glial lineage from the skin, we used desert hedgehog (Dhh)-Cre mice that express Cre recombinase in the peripheral glial lineage (Jaegle et al., 2003). Analysis of β-galactosidase expression in Dhh-Cre/R26R mice revealed that β-galactosidase-positive cells in the bulge co-express p75NTR and Sox10, as seen before in Wnt1-Cre/R26R, Ht-PA-Cre/R26R, and Dct-Cre/R26R mice. In contrast, pigmented melanocytes in the bulb were β-galactosidase negative, indicating that cells labeled in Dhh-Cre/R26R mice are not related to the melanocyte lineage. Moreover, direct isolation of EYFP-positive cells from Dhh-Cre/R26R-EYFP mice resulted in drastic enrichment of sphere-forming cells. Intriguingly, in agreement with previous publications, we failed to derive cells with sphere-forming features from sciatic nerves, demonstrating that only nerves or nerve endings in the skin, but not peripheral nerves in general contain cells with stem cell properties.

4.2.2. SKPs in the trunk skin: a dermal papilla stem cell originating from the mesoderm

Because the (neural crest-derived) dermal papilla of whisker follicles was identified as a niche for SKPs from facial skin (Fernandes et al., 2004), it was uncertain until recently whether trunk SKPs are also associated with (mesoderm-derived) dermal papilla or whether they actually represent NCSCs originating from other structures than the dermal papilla. A first hint that SKPs do not correspond to bona fide NCSCs was provided by an extensive transcriptome analysis demonstrating that neither facial nor back skin dermal papilla exhibit a NCSC molecular signature characteristic for both embryonic and EPI-NCSCs (Hu et al., 2006). It was the availability of transgenic mice expressing GFP in the dermal papilla that allowed Miller and colleagues to connect SKPs of the trunk skin with dermal papilla (Biernaskie et al., 2009). At postnatal stages and in adulthood, Sox2-GFP is expressed in the dermal papilla of anagen follicles. FACS-isolated cells can regulate hair follicle morphogenesis and localize to reconstituted dermal papilla, dermal sheath, and dermis, thus exhibiting features of dermal stem cells. In addition, however, Sox2-positive dermal papilla cells are spherogenic and behave like SKPs, in that they can be passaged extensively and, upon culturing, give rise to neural and non-neural cell types in vitro. Moreover, cultured dermal papilla cells are able to a certain extent to localize to nerves and DRG after transplantation in the neural crest migratory stream of chicken embryos, as has been shown before for SKPs. Finally, SKPs and Sox2-GFP cells from the dermal papilla share a similar global gene expression pattern, further confirming the dermal papilla nature of SKPs. Consistent with the idea that SKPs are of dermal origin, human SKPs have been isolated from foreskin lacking hair follicles (Toma et al., 2005). Thus, although not of neural crest origin in the trunk, SKPs appear to exhibit or can acquire features of NCSCs, being able to produce neural cell types normally not derived from dermal cells.

Table 2. Multipotent stem cells in the skin

5. Conclusive remarks and perspective

The past years have seen a growing number of reports on multipotent NCSCs from different stages and locations. These findings were often as unexpected as exciting, such as the identification of NCSCs in the bone marrow (Nagoshi et al., 2008; Takashima et al., 2007), shedding new light on the debate of whether or not “mesenchymal stem cells” exhibit neural potential. In addition, SKPs with a completely different developmental history than NCSCs appear to display striking similarities to NCSCs with respect to their developmental potential (Biernaskie et al., 2009). Whether these similarities reflect intrinsic properties of the cells in situ or whether they are acquired in culture remains to be shown. In any case, the recent discoveries raise the question of how multipotent cells with distinct origins evolve to share potentials. Possibly, dynamic epigenetic modifications might allow cells to adopt a comparable stem cell state by developmental reprogramming.

The availability of adult stem cells with a broad potential and present in easily accessible tissues such as bone marrow and skin makes these cells attractive candidates for future therapeutic applications. Indeed, EPI-NCSCs survived, integrated, differentiated into neuronal and glial cells, and associated with host neurites in the lesioned spinal cord (Sieber-Blum et al., 2006). Importantly, SKPs have the capacity to promote remyelination in a model of spinal cord injury (Biernaskie et al., 2007) and to generate Schwann cells that myelinate axons upon transplantation into the injured peripheral nerves of mutant mice (McKenzie et al., 2006). Additionally, SKPs can serve as source of mesenchymal cell types, such as osteocytes and chondrocytes that functionally integrate into bone tissue in vivo (Lavoie et al., 2009).

However, although adult stem cells can share properties, their fate in vivo and their developmental and therapeutic potential are presumably influenced by intrinsic characteristics imposed by origin and spatiotemporal cues. Indeed, using conditional genetic approaches in animal model systems, combined with various cell biological assays, we and others have previously demonstrated that fate and growth of embryonic and fetal NCSCs are regulated by distinct signaling networks acting in an area- and stage-specific manner (Falk and Sommer, 2009). It is thus timely and necessary to apply such technologies to adult NCSCs, in order to understand the mechanisms controlling adult NCSC populations in vivo. Such approaches will also help to gain insights into the physiological roles of endogenous adult NCSCs, which up to date remain mostly elusive. It is conceivable, though, that adult NCSCs play a role in tissue homeostasis and regeneration, similar to other stem cell types. Moreover, aberrant regulation of adult NCSCs might be implicated in the formation of tumors with a neural crest origin, such as melanoma. To tackle these issues seems to us one of the most urgent tasks of current day NCSC research.

Acknowledgments

Research in the authors laboratory is supported by the Swiss National Science Foundation, the National Research Program NRP63, the National Center of Competence in Research “Neural Plasticity and Repair”, the Vontobel Foundation, the Swiss Cancer League, UBS Wealth Management, and the University of Zurich.