This is the latest version of this chapter. The previous version can be found here.

Hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells (HSPCs) continuously egress out of the bone marrow (BM) to the circulation under homeostatic conditions. Their enhanced recruitment to the periphery in response to exogenous stimulation is a process, termed mobilization. HSPC mobilization is induced clinically or experimentally in animal models by a wide variety of agents, such as cytokines (e.g. G-CSF), chemotherapeutic agents (e.g. cyclophosphamide) and small molecules (e.g. the CXCR4 antagonist AMD3100). The major source for clinical transplantation protocols is via peripheral blood (PB) mobilization of BM derived HSPCs. Thus, deciphering mechanisms that regulate HSPC motility can be utilized for the development of improved mobilization regimens.

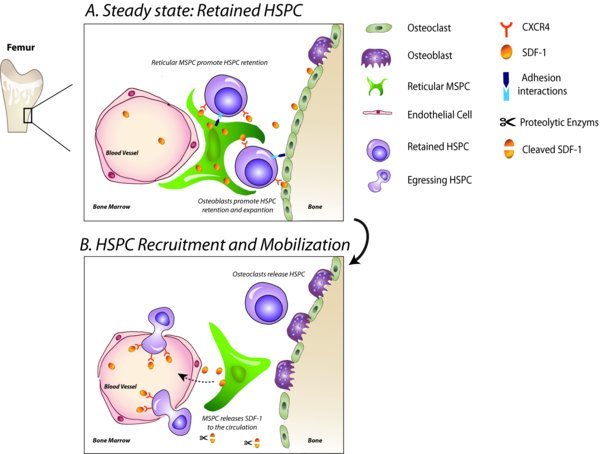

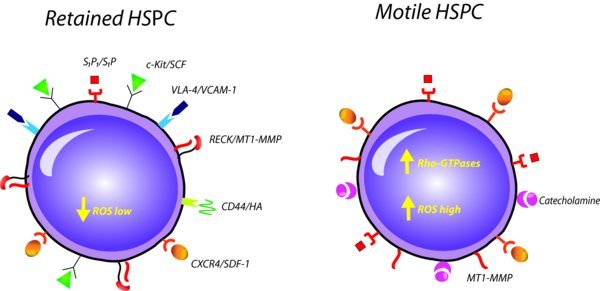

The chemokine stromal derived factor-1 (SDF-1, also termed CXCL12) and its major receptor CXCR4 are crucial in mediating both retention and mobilization of HSPCs, and this chapter will emphasize its recently revealed roles in directing steady state egress and rapid mobilization. Loss of retention is mediated by disruption of adhesion interactions, such as those mediated by integrins and CD44, and intrinsic signaling pathways such as Rho GTPases dependent signaling. Pivotal roles for the hemostatic fibrinolytic and stress-induced proteolytic enzymatic machineries in regulating HSPC recruitment are also discussed. Nevertheless, breakdown of adhesion interactions and activity of proteases are only part of the story, as accumulating evidences present the BM microenvironment, not only as maintaining HSPC quiescence and proliferation, but also as controlling HSPC retention and motility. Differentiating myeloid cells, bone remodeling by osteoblasts and osteoclasts, stimuli of the innate immunity as well as of the nervous system, including signals emanating the circadian clock, highly regulate various aspects of HSPC function, including egress, recruitment and mobilization. This review aims at presenting up to-date results concerning the dynamic interplay between the BM microenvironment and the HSPCs, focusing on molecular mechanisms that lead eventually to mobilization of HSPCs from the BM into the circulation.

1. Introduction

Hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs) mostly reside in the BM, where they undergo proliferation and multi-lineage differentiation, giving rise to mature leukocytes and erythrocytes, which are released in turn to the blood in order to carry out their function ((Orkin et al., 2008)). In fact, not only mature leukocytes circulate, but also small amounts of non-cycling HSPCs ((Lapidot et al., 2002)). Human umbilical cord blood (CB) contains relatively high amounts of CD34+ HSPCs (∼0.5%) ((Broxmeyer et al., 1996)), however, after birth their fraction in the PB decreases to ∼0.06% at steady-state conditions ((Korbling et al., 2001)). Although it could be interpreted that steady state PB HSPCs may reflect a leakage of the system, it is now believed that they play a role in homeostasis, such as repopulation of damaged BM regions and giving rise locally to myeloid dendritic cells as part of host immunity ((Massberg et al., 2007)). HSCs with repopulation capacity also circulate in the lymphatic system as part of host defense mechanisms ((Massberg et al., 2007)). Donor murine PB HSPCs are cleared very quickly, within a few minutes, from the circulation of intravenously transplanted congeneic recipients ((Wright et al., 2001)). By pairing congeneic mice and creating parabiotic mice with a shared blood system, it was revealed that HSCs rapidly and continuously migrate through the circulation, enabling functional re-engraftment of unconditioned BM ((Wright et al., 2001); (Abkowitz et al., 2003)). HSPC egress into the circulation is dramatically augmented in a process termed recruitment, during stress situations and upon demand of accelerated hematopoiesis ((Lapidot et al., 2002)). Proliferation (and differentiation) in the BM usually precedes enhanced progenitor cell egress ((Morrison et al., 1997)), and PB neutrophilia is associated with recruitment of HSPCs to the PB ((Levesque et al., 2007); (Roberts et al., 1997)). Enhanced HSPC egress and recruitment occurs following various stress situations, such as exercise ((Kroepfl et al., 2012)), adrenocorticotropic hormone administration ((Barrett et al., 1978); (Zaldivar et al., 2007)), inflammation (mimicked by LPS or endotoxin administration) ((Benner et al., 1981); (Cline et al., 1977)), bleeding ((Kollet et al., 2006)), administration of cytotoxic drugs ((1989); (To et al., 1984)) and even psychological anxiety ((Elsenbruch et al., 2006)).

Since HSCs are strongly retained in specialized niches in the BM ((Adams et al., 2006)–(Lo Celso et al., 2011)) (also reviewed in this StemBook), the mere mechanistic concept of cell egress is deliberate detachment of HSCs and their active trafficking from the BM to the blood stream in order to accommodate blood cell replenishment on demand. Hence, HSC recruitment to the PB is not a simple direct outcome of proliferation and passive release to the blood. Stress-induced HSPC recruitment is a complex multi-step process, involving intrinsic motility mechanisms, activities of various cytokines, chemoattractants, proteolytic enzymes and other extrinsic factors that enable detachment of HSPCs from their niches. The BM niches serve to prevent HSPC migration and proliferation via adhesion interactions, and thereby breakdown of these interactions are essential for the HSPC motility as part of their egress. Growing evidence for the involvement of other cellular players, such as neutrophils, macrophages, osteoblasts, osteoclasts and neurons in regulation of the increased HSPC motility will be discussed. In our previous chapter ((Lapid et al., 2008)), we also discussed functional murine models for clinical HSC mobilization, through describing mobilizing factors, deciphering pathways and molecular mechanisms promoting mobilization, presenting a broader view on the microenvironmental regulation of this process. This chapter is aimed at summarizing and presenting the up-to-date insights regarding mechanistic aspects of mobilization as well as recent data on steady state and rapid HSPC mobilization mechanisms. We will discuss the putative contribution of the nervous system as well as the myeloid lineage to the HSC maintaining niche, focusing on BM-resident myeloid cells, including macrophages and osteoclasts. In addition, recent findings on the involvement of the complement cascade and the fibrinolytic system are discussed. Currently, the subject of mobilization is at the center of an intense debate. The updated chapter will also describe our point of view regarding some clinical aspects.

2. Cytokine-induced mobilization

The majority of clinical BM transplants are performed using HSPCs that have been isolated from the PB following their mobilization from the BM. A long array of mobilizing agents is used clinically or experimentally in animal models to induce mobilization, the concept of which is to mimic the process of physiological stress-induced immature cell recruitment. A regimen that is based on administration of myeloid cytokines with or without chemotherapeutic agents for several consecutive days is a standard protocol for mobilizing HSCs in human patients or healthy donors ((Verma et al., 1999); (Schwartzberg et al., 1992)). The myeloid cytokine granulocyte colony stimulating factor (G-CSF) is the most effective mobilizing agents used today ((Korbling et al., 2001); (Sica et al., 1992)). Repetitive G-CSF stimulations favor accelerated myeloid hematopoiesis and indirectly enhance HSPC motility and recruitment to the circulation. Indeed, mobilized human and murine HSPCs are characterized by increased endogenous motility and homing rates, therefore mobilized PB HSPCs demonstrate higher engraftment capacities in comparison to steady state BM HSPCs ((Bonig et al., 2007)). Furthermore, it was demonstrated that HSPCs mobilized by G-CSF are distinct from those which reside in the BM under steady state conditions; mobilized HSPCs express lower levels of c-Kit, the integrin VLA-4 and CXCR4 and are more quiescent than their BM counterparts ((Greenbaum et al., 2011)).

The cytokines stem cell factor (SCF) and Flt3-ligand (FLT3-L), which are required for HSC self-renewal/survival and early hematopoiesis respectively, are also known to induce HSPC mobilization alone or in combination with G-CSF or other cytokines ((Papayannopoulou et al., 1997)–(Yan et al., 1994)). As compared to administration of cytokines, such as G-CSF, that require daily stimulations in order to mobilize HSPCs, there are several cytokines and chemokines that are able to induce rapid mobilization that ranges between 20 minutes to several hours, such as the CXCR2 ligand GROβ ((Fukuda et al., 2007); (Pelus et al., 2008)). These rapid mobilizers do not act directly on HSPCs, but rather trigger activation of neutrophils that secrete proteolytic enzymes, enabling rapid HSPC egress (further discussed under the “proteolytic activity” section).

Interestingly, there are cytokines that promote retention rather than egress. For example, it has been demonstrated that epidermal growth factor (EGF) treatment inhibits G-CSF-induced HSPC mobilization in mice, while EGF receptor inhibitor augments it ((Ryan et al., 2010)). Accordingly, mutant mice with lower EGF receptor kinase activity exhibit enhanced mobilization potential ((Ryan et al., 2010)). Another example is the pro-angiogenic vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF). Administration of VEGF, followed by treatment of mice with AMD3100, resulted in mobilization of both endothelial progenitor cells (EPCs) and stromal progenitor cells, while suppressing HSPC mobilization, suggesting a differential mobilization mechanisms for different subsets of BM progenitors ((Pitchford et al., 2009)). In contrast to G-CSF, VEGF had no impact on BM SDF-1 levels or expression of CXCR4, indicating a mobilization induction mechanism of EPCs that was not resulted by disruption of the SDF-1/CXCR4 axis ((Pitchford et al., 2009)). The central roles of the SDF-1/CXCR4 pathway are discussed below. In this chapter, we focus on mechanisms driving G-CSF-induced and AMD3100-induced HSPC mobilization, which are the most common mobilizing agents used experimentally and clinically.

3. The SDF-1/CXCR4 pathway

SDF-1 is a chemokine able to strongly attract human and murine HSPCs ((Peled et al., 1999)–(Mohle et al., 1998)). In addition to its chemotactic function, SDF-1 has important roles in HSPC homing, retention, survival and quiescence. SDF-1 is highly expressed by various BM stromal niche cells: endosteal bone lining osteoblasts ((Ponomaryov et al., 2000)), BM endothelium ((Ceradini et al., 2004)), CXCL12 abundant reticular (CAR) cells ((Sugiyama et al., 2006)), reticular Nestin-GFP+ mesenchymal stem and progenitor cells (MSPCs) ((Mendez-Ferrer et al., 2010)), human reticular CD146+ MSPCs ((Sacchetti et al., 2007)) and perivascular reticular Leptin receptor+ cells ((Ding et al., 2012)), thereby attracting circulating CXCR4+ HSPCs to their BM niches. Blocking CXCR4 function by neutralizing antibodies impairs homing of transplanted human CD34+ HSPCs to the BM of immune deficient mice ((Kollet et al., 2001)), accompanied by impaired engraftment ((Peled et al., 1999)). Impairment of SDF-1 or CXCR4 in murine embryos results in multiple lethal defects, including lack of stem cell seeding of the BM ((Nagasawa et al., 1996); (Zou et al., 1998)). In order to circumvent lethality, conditional knock-out (KO) models were established. Induced deletion of CXCR4 in the hematopoietic system of the adult mouse or SDF-1 in the BM stroma, lead to severely reduced BM cellularity and HSC numbers as well as impaired repopulation capacity ((Sugiyama et al., 2006); (Tzeng et al., 2011)). Of interest, CXCR4 KO HSCs or HSCs in SDF-1 KO mice are pushed into the cell cycle, resulting in increased numbers of more mature progenitors, but loss of function in general ((Sugiyama et al., 2006); (Tzeng et al., 2011); (Nie et al., 2008)). These observations implicate CXCR4 in promoting quiescence of HSCs, explaining why CXCR4 conditional KO mice have reduced survival following myeloablative treatment ((Sugiyama et al., 2006)) or irradiation ((Foudi et al., 2006)). Conditional deletion of CXCR4 or SDF-1 also results in dramatically increased HSPC numbers in the PB and spleen ((Tzeng et al., 2011); (Nie et al., 2008)), suggesting that blocking CXCR4 hampers their retention in the BM. CXCR4 has selective chemical antagonists, among which are AMD3100 and T-140. Upon AMD3100 administration, mouse, human and non-human primate HSPCs undergo rapid mobilization within hours ((Broxmeyer et al., 2005)–(Liles et al., 2003)) and the mobilized HSPCs demonstrate increased in vivo repopulation potential. Similarly, T-140 induces mobilization of primitive murine repopulating cells ((Abraham et al., 2007)). Both AMD3100 and T-140 synergistically augment G-CSF-induced mobilization. AMD3100 is the only chemokine receptor antagonist utilized clinically for inducing mobilization, either alone ((Devine et al., 2008)) or in combination with G-CSF administration ((Liles et al., 2003)). AMD3100 has been shown to be an effective mobilizing agent in murine models that are known to be poor mobilizers in response to G-CSF, including diabetic mice ((Ferraro et al., 2011)), Fanconi anemia model ((Pulliam et al., 2008)) and CD26 deficient mice ((Paganessi et al., 2011)), implying its clinical potential. Nevertheless, disruption of the SDF-1/CXCR4 interactions in the BM as a mean to mobilize HSPCs is over-simplified, as described herein by the observations of dynamic SDF-1 levels in steady state or upon stress as well as novel rapid HSPC mobilization mechanisms.

3.1. The dynamics in SDF-1 levels

The essential role of SDF-1/CXCR4 in retention can be inferred from the observations that following G-CSF administration, SDF-1 levels in the BM are transiently increased followed by their downregulation at both protein ((Levesque et al., 2003); (Petit et al., 2002)) and mRNA ((Semerad et al., 2005)) levels, enabling transient and local SDF-1 gradients towards the blood. Such downregulation of SDF-1 in the BM was also observed upon administration of SCF and FLT3-L ((Christopher et al., 2009)). In addition, CXCR4 upregulation is observed on immature murine BM cells following G-CSF treatment as well as on immature human CD34+ cells and primitive CD34+CD38− cells resident in the BM of G-CSF-treated chimeric mice ((Petit et al., 2002)). Blocking CXCR4 or SDF-1 reduces G-CSF-induced mobilization, thus demonstrating an active role for SDF-1/CXCR4 in mobilization of murine progenitors ((Petit et al., 2002)). Supporting the role of SDF-1/CXCR4 in HSPC mobilization from the BM, CXCR4 KO chimeric mice, which were transplanted with CXCR4 KO fetal liver cells, fail to mobilize upon G-CSF treatment ((Christopher et al., 2009)).

Interestingly, diabetes in mice is associated with multiple hematopoietic defects, including a reduction in BM HSPCs and their repopulation capacity in competitive transplantation assays ((Orlandi et al., 2010); (Mangialardi et al., 2012)). Patients with both type I and II diabetes mellitus exhibit lower numbers of circulating pro-angiogenic cells and EPCs, a phenomena that is associated with diabetic vasculopathies, and respond poorly to G-CSF administration ((Fadini et al., 2005); (Fadini et al., 2012)). This clinical data is supported experimentally in diabetic rats that were unable to recover after hind limb ischemia, pointing towards a defect in progenitor cell mobilization ((Fadini et al., 2005); (Caballero et al., 2007)). In support, diabetic mice show increased HSPC retention in the BM and poor HSPC mobilization upon G-CSF ((Ferraro et al., 2011)). Moreover, no enhanced HSPC egress in response to wounding was observed in diabetic mice in comparison to their normal counterparts, resulting in delayed wound healing ((Tepper et al., 2010)). In both studies, the suggested mechanism was impaired down-modulation of SDF-1 in the BM. In order to correct this phenotype in diabetic mice, AMD3100 that is known to induce SDF-1 release from the BM to the circulation ((Petit et al., 2007); (Dar et al., 2011)), has been given. As a result, mobilization of BM-derived progenitors has been obtained and tissue repair has been improved as a consequence. Interestingly, diabetic pathology is associated with increased CD26 plasma activity in both human patients and a rat model, suggesting a possible mechanism by which altered SDF-1 levels lead to impaired mobilization ((Ferraro et al., 2011); (Fadini et al., 2013); (Tepper et al., 2010)).

As compared to SDF-1 in the BM, SDF-1 in the PB is short-lived and is prone to proteolysis by proteases, such as CD26 ((Christopherson et al., 2003); (Christopherson et al., 2002)) (discussed under “proteolytic activity”). SDF-1 by itself can activate proteases, such as the metalloprotease MMP-9, participating in the enhanced migration capacity and recruitment of HSPCs to the periphery ((Kollet et al., 2003); (Janowska-Wieczorek et al., 2000)). These observations suggest that SDF-1 levels in the PB are dynamically regulated during homeostasis in addition to its major role in retention of HSPCs in the BM. Recent findings revealed circadian oscillations of SDF-1 levels in the BM, affecting retention of HSPC and consequently their steady state egress rates to the PB ((Mendez-Ferrer et al., 2008)) (further discussed under the “the nervous system” section). In other words, circulating HSPC numbers are in fact directly controlled by the tight regulation of SDF-1 levels. Thus, it is presumed that increased SDF-1 levels in the PB may attract HSPCs and thereby increase cell egress to the circulation. For instance, artificially elevating SDF-1 plasma levels by adenoviral vector expressing SDF-1 or using an analog peptide for SDF-1 causes HSPC mobilization ((Hattori et al., 2001); (Pelus et al., 2005)). Likewise, repetitive daily administrations of SDF-1 for five consecutive days induce HSPC mobilization ((Kollet et al., 2006)). Administration of the sulfated polysaccharide fucoidan leads to mobilization in mice and non-human primates ((Sweeney et al., 2000)). In follow-up studies, it was found that fucoidan competes with SDF-1 for binding heparan sulfate proteoglycans in the BM, subsequently releasing SDF-1 into the blood ((Sweeney et al., 2002); (Hidalgo et al., 2004)). Of note, injection of neutralizing SDF-1 antibodies in fucoidan treated mice, reduced mobilization of HSPCs, but not mature WBCs, revealing higher dependence on SDF-1 among immature cells ((Sweeney et al., 2002)). It is logical to assume that hampering SDF-1/CXCR4 signaling in the BM would result in loss of retention. Nonetheless, when the Met-SDF-1β analog, which induces prolonged CXCR4 desensitization, was given to mice, it resulted in only a modest mobilization ((Shen et al., 2001)), suggesting that active SDF-1/CXCR4 signaling is required.

3.2. Rapid HSPC mobilization

The concept of dynamic SDF-1 levels also in the PB, affecting HSPC recruitment to the circulation, has been introduced recently based on the results obtained by application of the CXCR4 “antagonist” AMD3100. It has been hypothesized that AMD3100 administration disrupts SDF-1/CXCR4 interactions in the BM, thus leading to the loss of HSPC retention ((Broxmeyer et al., 2005)). More recently, Dar and colleagues presented a more complex scenario ((Dar et al., 2011)). Blocking the SDF-1/CXCR4 axis using neutralizing antibodies to either SDF-1 or CXCR4 in AMD3100-treated mice, reduced mobilization of HSPCs, but not mature WBCs, further strengthening the hypothesis that this pathway is preferential for immature cells. Administration of neutralizing antibodies alone in steady state surprisingly reduced homeostatic HSPC egress rather than inducing it, refuting the assumption that disruption of SDF-1/CXCR4 interactions in the BM is sufficient for inducing HSPC mobilization. Strikingly, in response to AMD3100 administration, SDF-1 concentration in the BM transiently increases followed by its release to circulation, resulting in increased PB SDF-1 levels ((Petit et al., 2007); (Dar et al., 2011)). BM stromal cells also functionally express CXCR4 and are able to secrete SDF-1 as part of HSPC recruitment ((Schajnovitz et al., 2011); (Dar et al., 2005)). It was found that in response to AMD3100, SDF-1 secretion from BM endothelial cells and osteoblasts and its release to the circulation is increased, further contributing to transient, local SDF-1 gradients towards the blood, after which motile HSPCs may follow ((Dar et al., 2011)). Such transient elevation in SDF-1 plasma levels, which is accompanied with HSPC mobilization, has been also observed upon administration of other CXCR4-binding compounds ((Berchanski et al., 2011)), fucoidan ((Sweeney et al., 2002); (Hidalgo et al., 2004)), glycosaminoglycan mimetics ((Albanese et al., 2009)) and catecholamines ((Dar et al., 2011)). On the other hand, reduction in plasma SDF-1 levels, accompanied by reduced HSPC egress, has been observed in mice treated with antagonists of β2-adrenergic receptors or sphingosine-1-phosphate receptor 1 (S1P1) ((Dar et al., 2011); (Golan et al., 2012)). In support, positive correlations between the numbers of circulating EPCs and plasma SDF-1 levels have been detected in murine ischemic models ((De Falco et al., 2004)) and in human patients ((Smythe et al., 2008); (Bogoslovsky et al., 2011)). Rapid mobilization by AMD3100 does not end only at regulating SDF-1 levels, but also induces MMP-9 and uPA activation (further discussed under “proteolytic activity” section) in a CXCR4/JNK dependent manner, supporting an active rather than a passive rapid mobilization mechanism ((Dar et al., 2011); (Golan et al., 2012)). Notably, it was recently shown that AMD3100 administration also mobilizes EPCs, promoting cardiac recovery following injury ((Jujo et al., 2012)). In this study, eNOS signaling, MMP-9 activity and release of soluble SCF were involved. In an editorial point of view on this study, it has been suggested that most probably SDF-1 release is involved as well in the induction of EPC mobilization ((Jujo et al., 2012); (Limbourg et al., 2012)). In addition, immature human CD34+ cells derived from mobilized PB of G-CSF+AMD3100-treated chimeric mice demonstrate increased SDF-1-induced migration in vitro as compared to cells derived from G-CSF only treated chimeric mice ((Broxmeyer et al., 2005)). These findings are supported by a similar observation in non-human primates ((Larochelle et al., 2006)). It is therefore concluded that the inhibitory effect of AMD3100 may be short-lived and active SDF-1/CXCR4 dependent mechanisms take over, inducing preferential and rapid HSPC mobilization. Altogether, dynamic SDF-1 levels in the BM and the PB directly regulate both physiological and stress-induced egress of CXCR4+ HSPCs and thus are tightly regulated by different mechanisms, including SDF-1 expression by BM stromal cells and its release to the circulation, after which HSPCs follow. However, except for upstream regulators affecting HSPC motility as part of egress and mobilization, what are the intrinsic signaling pathways involved?

4. HSPC mobilization and intracellular signaling

4.1. The roles of small GTPases

Rho guanosine triphosphatases (GTPases) are a class of intracellular signaling enzymes that serve as crucial regulators of the actin cytoskeleton, affecting HSPC migration and adhesion, but also regulate the expression of genes that are responsible for proliferation and survival pathways ((Cancelas et al., 2009)–(Williams et al., 2008)). Rho GTPases include the Rac, Rho and CDC42 sub-families to which different roles in HSPC function are attributed. It was shown that a variety of cytokines, chemokines, growth factors, integrins and the major axes of SDF-1/CXCR4 and SCF/c-Kit signal through Rho GTPases, pointing at their importance in hematopoiesis and HSPC motility ((Cancelas et al., 2009); (Mulloy et al., 2010)). Notably, the expression of Rac2 is specific to hematopoietic cells, while Rac1 and Rac3 are widely expressed ((Didsbury et al., 1989)). Several studies provide evidence regarding the roles of Rac1, Rac2 ((Cancelas et al., 2005)–(Jansen et al., 2005)), Cdc42 ((Yang et al., 2007)) and RhoA ((Ghiaur et al., 2006)) GTPases in murine HSPC trafficking, localization and engraftment (reviewed in ((Williams et al., 2008))). Rac1/2 are activated in response to SDF-1 in HSPC ((Cancelas et al., 2005)), and Rac1/2-deficient HSPCs show reduced chemotaxis towards SDF-1 and β1 integrin-mediated adhesion in vitro ((Gu et al., 2003)). Of note, RhoH serves as a negative regulator of Rac1 activity in SDF-1-induced HSPC chemotaxis ((Chae et al., 2008)). Nonetheless, another companion of this sub-family, RhoA, positively regulates SDF-1-induced HSPC chemotaxis ((Ghiaur et al., 2006)). In vivo, Rac1 is required for the localization of HSPCs to BM endosteal region ((Cancelas et al., 2005)). The deletion of both Rac1 and Rac2 led to a massive egress of HPCs into the blood from the BM, whereas Rac1−/−, but not Rac2−/− HSPCs, failed to engraft in the BM of irradiated recipient mice ((Cancelas et al., 2005); (Gu et al., 2003)). The relevance of Rac activity to HSPC mobilization was further elucidated by applying a specific inhibitor of Rac activity (but not Cdc42 or RhoA activity) ((Gao et al., 2004)), resulting in mobilization within hours ((Cancelas et al., 2005)). Recently, it was shown that Rac1 activity leads to reversible conformational change in human CXCR4 that potentiates SDF-1/CXCR4 signaling, implying for a reciprocal cross-talk between these signaling pathways ((Zoughlami et al., 2012)). It is yet to investigate whether these findings are translated into physiological motility and retention mechanisms of HSPCs.

Cdc42–/– HSPCs demonstrate impaired migration, adhesion, homing, lodgment and repopulation capacities in addition to deregulated cell cycle ((Yang et al., 2007)). The phenotype is more severe than standalone deficiencies in Rac1 or Rac2 and resembles combined Rac1 and Rac2 deficiencies. Furthermore, a loss of HSPC retention is documented in Cdc42 deficient mice, resulting in high numbers of circulating HSPCs and in extramedullary hematopoiesis in the spleen and liver ((Yang et al., 2007)) as well as enhanced response to G-CSF ((Ryan et al., 2010)). It was found that EGF treatment activates Cdc42, while EGF receptor inhibitor inactivates Cdc42, negatively correlating with the effect on G-CSF-induced mobilization of HSPCs ((Ryan et al., 2010)) (also discussed in “cytokine-induced mobilization”). On the other hand, gaining Cdc42 activity is also incompatible with HSPC function, including motility, as shown by deletion of its negative regulator Cdc42GAP ((Wang et al., 2006)). Of interest, aged mice exhibit poor homing capacity ((Liang et al., 2005)) and increased mobilization capacity in response to G-CSF ((Xing et al., 2006)). Surprisingly, a gain of Cdc42 activity was detected in aged HSPCs, however, how it affects their function remains unknown. Recently, it has been revealed that gain of Cdc42 activity in aged HSCs leads to loss of polarity and function, which could be rescued by Cdc42 inhibition ((Florian et al., 2012)). Since cell polarity is important for directional migration and adhesion mechanisms, we suggest that motility and retention defects in aged mice may be attributed to increased CDC42 activity.

GTPases can be activated by guanine nucleotide exchange factors (GEFs) ((Rossman et al., 2005)). Vav proteins, for example, constitute a subfamily of GEFs known by their importance for various immune functions, in which Vav1 is expressed only by hematopoietic cells ((Turner et al., 2002)). Vav1–/– murine HSPCs have defective lodgment, poorly engraft and show lower rates of steady state egress ((Sanchez-Aguilera et al., 2011)). In addition, Vav1–/– HSPCs present abnormal migration response to SDF-1 gradient in vitro. When Vav1 deficient mice are treated with AMD3100, it mobilizes reduced numbers of progenitors compared with AMD3100-treated WT mice ((Sanchez-Aguilera et al., 2011)). Interestingly, G-CSF-induced mobilization, known to be mediated in part by SDF-1 down-regulation ((Petit et al., 2002); (Semerad et al., 2005)), was also severely impaired in Vav1 deficient mice. Thus, Vav1 is crucial in mediating HSPC response to physiologic or stress-induced changes in SDF-1 levels in the BM compartment ((Sanchez-Aguilera et al., 2011)).

Another important player in the field of GTPases-mediated activity and mobilization of HSPCs is R-Ras. R-Ras is a member of the Ras family of GTPases and was found to be required for adhesion-induced Rac activation, but the functional relationship between R-Ras and Rac is controversial ((Goldfinger et al., 2006)). R-Ras was identified as an intrinsic regulator of HSPC migration and recruitment by using KO and constitutively active R-Ras mutants ((Shang et al., 2011)). These data indicate that R-Ras negatively regulates Rac1/Rac2 activities and therefore mediates actin polymerization and migration, impacting HSPC trafficking in vitro and in vivo without affecting their proliferation. While BM homing of R-Ras deficient HSPCs is defective, their SDF-1-induced migration capacity in vitro and mobilization in response to G-CSF stimulation are even increased ((Shang et al., 2011)). In conclusion, intracellular signaling is required for HSPC migration capacity into and out of the BM to the circulation, indicating that active mechanisms underlie mobilization (e.g. by G-CSF or by AMD3100) and it should be regarded as an active process rather than passive detachment of cells from the BM niches and their release to the periphery.

4.2. SCF/c-Kit signaling

Not only GTPases mediate signaling that controls HSPC motility and recruitment in response to SDF-1/CXCR4 cues, but also receptor tyrosine kinases. The class III receptor tyrosine kinase c-Kit is expressed on all HSPCs, and the ligand for c-Kit, SCF, is constitutively produced by BM endothelial cells and perivascular stromal cells as well as by other stromal cells ((Ding et al., 2012); (Broudy et al., 1997)). Administration of a c-Kit neutralizing antibody to WT mice mobilized HSPCs and enhanced their engraftment most probably due to increased availability of niches in the BM ((Czechowicz et al., 2007)). Accordingly, it was shown that HSPC mobilization is markedly inhibited in mice that express mutated c-Kit with aberrant kinase activity, although the expression levels of c-Kit and SCF were normal ((Cheng et al., 2010)). In support of SCF/cKit role in HSPC retention, it was previously shown that G-CSF mobilizes HSPCs by triggering the enzymatic cleavage of membrane-bound SCF ((Heissig et al., 2002)). Release of soluble SCF is also observed following AMD3100 administration((Jujo et al., 2012)) In addition, administration of soluble c-Kit results in HSPC mobilization due to its capability to prevent SCF binding to endogenous c-Kit+ HSPCs ((Nakamura et al., 2004)). Intriguingly, SDF-1/CXCR4 interactions retain HSPCs in the BM by trans-activating c-Kit in a Src dependent manner, and that CXCR4 antagonism by AMD3100 mobilizes HSPCs by inhibiting c-Kit phosphorylation ((Cheng et al., 2010)). In addition, c-Kit deficient murine HSPCs display poor migration and adhesion capacities ((Kimura et al., 2011)). Hence, there is evidence for a cross-talk between SDF-1/CXCR4 and SCF/c-Kit signaling pathways, regulating HSPC retention. Much is unknown, including the downstream/inside-out signaling, at which SDF-1/CXCR4 and SCF/cKit converge and how the dynamic expression of one ligand affects response to the other one. Apart from gaining motility to induce recruitment of HSPCs to the PB, loss of retention obtained by disruption of adhesion interactions in the BM is also of significant importance, as discussed below.

5. Adhesion molecules and loss of retention

5.1. Adhesion interactions in the BM

HSCs reside at specialized niches in the BM ((Lo Celso et al., 2011)), supported by niche forming stromal cells, to which they tightly adhere. The recognition of adhesion receptors/ligands located at the surface of both HSPCs and stromal cells, as well as in the surrounding extracellular matrix (ECM), is therefore important to understand HSC regulation and maintenance ((Vermeulen et al., 1998); (Prosper et al., 2001)). For example, very late antigen-4 (VLA-4 or integrin α4β1) that binds to vascular cell adhesion molecule-1 (VCAM-1) on BM stromal cells or to fibronectin within the ECM is expressed also by HSPCs. Neutralization of VLA-4 leads to mobilization of HSPCs into the PB in both mice and primates ((Simmons et al., 1992)–(Papayannopoulou et al., 1995)). It was found that anti-VLA4/VCAM-1-induced HSPC mobilization requires cooperative signaling through the SCF/c-Kit pathway, demonstrated by the inability of mutant mice to mobilize ((Papayannopoulou et al., 1998)). In addition, anti-VLA-4 antibody administration augments G-CSF- and SCF-induced mobilization of long-term repopulating HSCs ((Craddock et al., 1997)). Expectedly, induced deletions of either VLA-4 or VCAM-1 resulted in accumulation of HSPCs in the PB ((Scott et al., 2003); (Ulyanova et al., 2005)) as well as disruption of the VCAM-1/VLA-4 axis with a small molecule inhibitor ((Ramirez et al., 2009)). Noteworthy, some of the adhesion molecules that are involved in the mechanism of homing to the BM, are not necessarily as important for cell egress out of the BM, and vice versa. Selectins are another set of adhesion molecules, which are involved in initial steps of HSPC homing to the BM ((Frenette et al., 1998); (Frenette et al., 2000)). Nevertheless, inhibition of selectins function as an inducer of mobilization remains controversial, due to the observation that fucoidan is able to induce mobilization also in mice lacking selectins ((Sweeney et al., 2000)).

CD44 is an important adhesion molecule that interacts with several ECM components, including hyaluronan ((Miyake et al., 1990)). Its involvement in normal and malignant human HSPC migration has been reported ((Naor et al., 2002)). During cell physiological egress, breakdown of this tight adhesion is a principal mechanism for releasing HSPCs from the BM, allowing them to be recruited to the blood, as noted in the following studies. Blocking CD44 function in mice results in mobilization ((Vermeulen et al., 1998)), and combination with G-CSF or anti-VLA-4 antibody administration, enhances their HSPC mobilization ((Christ et al., 2001)). Furthermore, CD44 was shown to be downregulated on mobilized immature human CD34+ cells ((Lee et al., 2000)). Studies using anti-CD44 antibodies revealed impaired homing of mouse hematopoietic progenitors to the BM and spleen ((Vermeulen et al., 1998); (Khaldoyanidi et al., 1996); (Avigdor et al., 2004)), whereas studies on CD44 KO mice demonstrated no defects in this process ((Oostendorp et al., 2000)), although a reduced myeloid progenitor cell egress from the BM to blood circulation was found ((Schmits et al., 1997)). Our group and others demonstrated that the CD44/hyaluronan axis is essential for both lodgment and engraftment of human CD34+ and murine HSPCs in the BM ((Avigdor et al., 2004); (Ellis et al., 2011)). Mechanistically, it was suggested that upon arrest on endothelial surfaces, SDF-1, expressed by the BM endothelium, facilitates the HSPC transendothelial migration by modulation of cell adhesion via increasing the avidity of membranal CD44 to hyaluronan in the BM sinusoidal endothelium ((Avigdor et al., 2004)). It should be noted that the membrane-bound protease MT1-MMP (further discussed under “proteolytic activity”) mediates pericellular ECM degradation, as well as shedding of adhesion molecules, including CD44, the pivotal adhesion molecule in the BM, contributing as a result to mobilization ((Itoh et al., 2006); (Vagima et al., 2009)). In addition to the expression levels of adhesion molecules, the adhesion capacity of HSPCs in the BM is also regulated, as discussed next.

5.2. Regulation of adhesion capacity

CD45 is one of the most abundant leukocyte cell surface glycoproteins and is expressed exclusively in cells of the hematopoietic system, except for erythrocytes and platelets. CD45 was shown to regulate different stages of lymphocyte maturation and activation ((Saunders et al., 2010)). Our group utilized the CD45 KO mouse model as well as blocking antibodies to human CD45 to investigate major parameters involved in progenitor cell function, including intrinsic motility properties and environmental regulation in the BM ((Shivtiel et al., 2008); (Shivtiel et al., 2011)). CD45 is particularly essential for mobilization and retention of BM HSPCs and not only of mature leukocytes, as blocking CD45 function or CD45 deficiency results in reduced stress-induced recruitment and homing of both human and murine HSPCs, in addition to the effects on mature leukocytes ((Shivtiel et al., 2008); (Shivtiel et al., 2011)). Mechanistically, reduced physiological egress of CD45 deficient leukocytes or CD45-blocked human HSPCs can be explained by Src-dependent hyper-adhesive phenotype and lower secretion of MMP-9 by CD45 deficient BM MNCs after their G-CSF stimulation ((Shivtiel et al., 2008)). Corroborating our studies, CD45–/– murine myeloma cells had a low MMP-9 secretion (the importance of which is further discussed under “proteolytic activity”) and a low surface expression of uPA receptor. Accordingly, the invasive and homing capacities of the CD45–/– murine myeloma cells were also impaired ((Asosingh et al., 2002)). Besides, it was shown that Src kinase, the CD45 substrate, is a potential target by which CD45 regulates the migration of hematopoietic cells ((Shivtiel et al., 2008)). Several studies support the involvement of Src kinases in adhesion and motility properties, as they were shown to regulate β1 and β2 integrins in various hematopoietic cells ((Thomas et al., 2004); (Roach et al., 1997)). Lack of Src kinases in mice enables enhanced G-CSF-induced mobilization of HSPCs due to elevated MMP-9 levels and enhanced breakdown of the adhesion molecule VCAM-1 ((Borneo et al., 2007)). Apart from CD45 and Src kinases, there might be other yet unrevealed regulators of adhesion capacity of HSPCs participating in physiological egress. Taken together, adhesion molecules play a major role in retention and therefore loss of their function, results in loss of retention and consequently HSPC egress. Notably, adhesion/de-adhesion interactions are required for the HSPC crossing through the BM endothelial barrier to the blood circulation and vice-versa. While crossing the endothelial barrier is widely studied in the context of homing ((Lapidot et al., 2005)), the mechanisms (whether overlapping or not) that govern active cell extravasation to the blood are hardly deciphered, but obviously require chemotactic cues, such as SDF-1 (see “the SDF-1/CXCR4 pathway”) and sphingosine-1-phosphate (S1P) (see “bioactive lipids-induced mobilization”). Nevertheless, another central mechanism by which adhesion interactions are disrupted during HSPC recruitment and mobilization involves proteolytic cleavage, as discussed herein.

6. Proteolytic activity

6.1. Serine- and metallo-proteases

Observations that following G-CSF administration, neutrophils undergo proliferation and activation, pinpoint at a possible role of neutrophils in the process ((Falanga et al., 1999)) (the involvement of neutrophils in HSPC mobilization will be further discussed under the “involvement of the innate immunity”). Previously, it was found that enzymes secreted by neutrophils are capable of cleaving VCAM-1, a major player in retention, both in vitro and during G-CSF-induced mobilization ((Levesque et al., 2001)). Other retention factors were shown to be cleaved by these serine proteases include c-Kit ((Levesque et al., 2003)), SCF ((Heissig et al., 2002)), SDF-1 ((Petit et al., 2002)) and CXCR4 ((Levesque et al., 2003); (Valenzuela-Fernandez et al., 2002)). Matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs) are a family of proteases that play a significant role in transendothelial migration and ECM degradation, one of which is MMP-9, which is secreted by neutrophils, but also by other cells in the BM ((Page-McCaw et al., 2007); (Zitka et al., 2010)). Following mobilization in mice with various cytokines, active MMP-9 plasma levels are elevated ((Pruijt et al., 1999)–(Shirvaikar et al., 2012)), and its inhibition subsequently results in reduced HSPC mobilization. MMP-9 was found to cleave c-Kit ((Levesque et al., 2003)) and membrane bound SCF ((Heissig et al., 2002)), releasing a soluble SCF. Soluble SCF, in turn, enhances cell motility and egress. In spite of these observations, mice lacking neutrophil secreted enzymes, neutrophil elastase (NE) and cathepsin G (CG), MMP-9 or dipeptidyl peptidase I, which is an enzyme required for activation of serine proteases, exhibit normal G-CSF-induced mobilization, pointing at multiple and redundant levels of proteolytic activity during the stress-induced mobilization process ((Levesque et al., 2004)). SDF-1 still underwent cleavage in NE and CG double KO mice, but VCAM-1 did not. Thereby, redundancy between activities of neutrophil proteases may occur as well as independent mechanisms for inducing cell egress.

Apart from neutrophil proteases, other proteases play a role during cell egress. CD26 (or dipeptidyl peptidase IV) is expressed by HSPCs and is able to cleave SDF-1, the truncated form of which acts as an antagonist of CXCR4-dependent chemotaxis ((Christopherson et al., 2003)). As a consequence, G-CSF-induced HSPC mobilization is reduced either upon CD26 inhibition ((Christopherson et al., 2003)) or in mice lacking CD26, compared to their wild-type counterparts ((Christopherson et al., 2003)). Interestingly, the osteoclast specific protease, Cathepsin K, has been shown to promote HSPC egress by cleaving endosteal components ((Kollet et al., 2006)) (described in “involvement of osteoclasts” in this chapter). SDF-1 central role in regulating physiological HSPC egress is also reflected by its ability to upregulate the expression of MMP-2, MMP-9 and membranal type I MMP (MT1-MMP or MMP-14) on human CD34+ cells ((Janowska-Wieczorek et al., 2000); (Shirvaikar et al., 2008)). MT1-MMP has been implicated in angiogenesis, bone development, atherosclerosis, inflammation, wound healing and cancer progression by virtue of its ability to degrade several ECM macromolecules and activate other proteolytic enzymes ((Itoh et al., 2006); (Zitka et al., 2010); (Sato et al., 2010)–(Seiki et al., 2003)). In addition, MT1-MMP is able to promote human and murine monocyte/macrophage migration in vitro ((Sakamoto et al., 2009); (Matias-Roman et al., 2005)). It is therefore not surprising that MT1-MMP, which is also expressed by BM stromal cells and immature hematopoietic cells, regulates the migration of human and murine HSPCs ((Vagima et al., 2009)) and murine hematopoiesis in general via hypoxia inducible factor-1 (HIF-1) dependent mechanisms ((Nishida et al., 2012); (Rodriguez et al., 2010)). RECK is suggested to act as a membrane-anchored inhibitor of MT1-MMP, MMP-2, and MMP-9 expression and activation ((Noda et al., 2007); (Oh et al., 2001)). We have recently reported a positive correlation between MT1-MMP expression and the clinical mobilization potential in both healthy donors and patients. On the other hand, the expression of RECK is low in circulating human HSPCs as compared to BM resident HSPCs ((Vagima et al., 2009)). The importance of MT1-MMP in HSPC mobilization was assessed as blocking of MT1-MMP function by neutralizing antibodies interfered with G-CSF–induced mobilization of human HSPCs and maturing cells in a chimeric mouse model, whereas diminishing RECK activity facilitated human CD34+ cell release to the circulation. These data were further corroborated by the impaired G-CSF-induced mobilization of HSPCs from MT1-MMP deficient mice as compared to WT littermates ((Vagima et al., 2009)). Mechanistically, MT1-MMP mediates pericellular ECM degradation, as well as shedding of adhesion molecules, including CD44 ((Itoh et al., 2006)) (further discussed under “adhesion molecules and loss of retention”), resulting in enhanced HSPC motility and contributing to their egress. Taken together, these results present a novel proteolytic axis in the regulation of HSPC motility and stress-induced recruitment ((Vagima et al., 2009)). It is yet to determine whether other mobilization procedures utilize this axis as well. Of interest, it was reported that catecholaminergic neurotransmitters increase MT1-MMP and MMP-2 expression in vitro on immature human cord blood CD34+ cells, which might contribute to their improved migration and BM engraftment ((Spiegel et al., 2007)). The contribution of the nervous system in general, specifically the sympathetic system, will be separately discussed in the chapter. In summary, there is abundance of observations demonstrating involvement of versatile proteolytic enzyme activity in facilitating mobilization of HSPCs out of the BM to the circulation via cleavage of adhesion molecules, degradation of ECM components and permeability of the endothelium. Although there are indications for few upstream regulators, such as RECK, it is poorly deciphered how proteolytic activity is regulated in retention or triggered upon stress.

6.2. Lipid rafts and mobilization

Lipid rafts have been shown to orchestrate the interaction of the small GTPases, Rac and Rho, with their downstream effectors, controlling cell migration and adhesion ((Gu et al., 2003); (del Pozo et al., 2004)–(Gomez-Mouton et al., 2004)) (the roles of GTPases are further discussed under “intracellular signaling and HSPC mobilization”). Optimal signaling transduced from CXCR4 is dependent on its incorporation into membrane lipid rafts ((Nguyen et al., 2002); (Wysoczynski et al., 2005)). Notably, during HSPC migration, SDF-1/CXCR4 signaling takes place within lipid rafts, where CXCR4 and Rac-1 assemble, allowing an optimal chemotactic response to SDF-1 ((Wysoczynski et al., 2005)). Moreover, G-CSF was shown to increase incorporation of MT1-MMP into lipid rafts, leading to increased ECM degradation, activation of proMMP-2 and enhanced HSPC egress from the BM in a PI3K-dependent mechanism ((Shirvaikar et al., 2010)). The MT1-MMP activation of proMMP-2 in the BM microenvironment is important, because active MMP-2 not only initiates the activation of other MMPs that play a role in matrix remodeling, but also inactivates SDF-1, CXCR4 and adhesion molecules, processes that facilitate recruitment of HSPCs from the BM across the ECM and endothelium ((van Hinsbergh et al., 2008)). Taken together, G-CSF-induced MT1-MMP upregulation and redistribution into lipid rafts seems to be a mechanism that contributes together with other proteolytic enzymes to a highly proteolytic microenvironment in the BM and a greater invasiveness of hematopoietic cells, including HSPCs ((Shirvaikar et al., 2010)). During HSPC migration, SDF-1/CXCR4 and Rho GTPase signaling events mainly takes place within lipid rafts, and since these signaling pathways play crucial roles in HSPC physiological egress and mobilization, we can imply for the significant involvement of lipid rafts as well.

7. The fibrinolytic system

A novel paradigm by which fibrinolytic enzymes mediate systemic and localized effects in the BM was introduced by Heissig and colleagues that established a role for Plasminogen (Plg) activation in hematopoiesis ((Heissig et al., 2007)). The serine protease plasmin plays an important role in fibrinolysis and can degrade ECM molecules ((Herren et al., 2003)). Plg, its inactive proenzyme, can be activated by tissue-type plasminogen activator (tPA), urokinase-type plasminogen activator (uPA) and other serine proteases. Importantly, during fibrinolysis or in response to injury, plasmin participates in the activation of MMPs ((Lijnen et al., 1998); (Lijnen et al., 1998)). It was shown that tPA, either provided by BM cells or exogenously administered, causes MMP-2 and MMP-9 activation in cultured BM stromal cells ((Heissig et al., 2007)). Several reports have introduced recently the involvement of the fibrinolytic system in the HSPC mobilization process. Plasmin secretion in the BM was found to be transiently increased during mobilization ((Tjwa et al., 2009)). Genetic deficiency of various endogenous inhibitors of this pathway as well as thrombolytic agents, mimicking plasmin activity, increase steady state egress of HSPCs or enhance G-CSF-induced mobilization of HSPCs in mice ((Tjwa et al., 2008)). Plg KO mice present impaired mobilization of HSPCs in response to G-CSF due to reduced MMP-9 activity and abolished upregulation of CXCR4 expression ((Tjwa et al., 2009); (Gong et al., 2011)). Restoration of MMP-9 activity was able to recover mobilization capacity in these Plg KO mice, further supporting the importance of MMPs in the HSPC mobilization processes ((Gong et al., 2011)). Circulating uPA has been recently shown by us to be activated in a CXCR4/JNK-dependent manner following administration of the rapid mobilizer AMD3100 in mice ((Dar et al., 2011)), however the precise roles of uPA or the involvement of tPA in HSPC mobilization have yet to be deciphered.

Recently, Tjwa and colleagues showed that membrane-anchored plasminogen activator (urokinase receptor) MuPAR is expressed by HSPCs and regulates their cell-cycle status, thereby preventing abnormal HSPC proliferation and apoptosis, while ensuring chemoprotection ((Tjwa et al., 2009)). Detection of intact MuPAR on BM HSPCs was reduced during mobilization in WT mice, and since such a decrease did not occur in Plg KO mice, it is suggested that plasmin mediates cleavage of MuPAR. Notably, cleaved forms of uPAR were detected in human G-CSF mobilized blood samples ((Selleri et al., 2005)). The authors have revealed chemotactic properties for this cleaved form that might assist in recruitment of HSPCs to the periphery ((Selleri et al., 2005)). Indeed, administration of a soluble uPAR peptide in mice causes HSPC mobilization by itself, which is comparable to that of G-CSF administration ((Selleri et al., 2006)). Taken together, it is pursued that plasmin is a candidate proteinase to inactivate MuPAR on HSPCs during mobilization and release functional cleaved form of uPAR to the periphery. However, the possibility that plasmin may also regulate HSPC mobilization via additional mechanisms, such as via cleavage of membrane-bound SCF is still an open question. Regardless of the mechanisms, MuPAR therefore resembles other HSPC receptors, such as Tie-2 and c-Kit, which are also essential for HSPC marrow pool size and retention in the BM ((Broudy et al., 1997); (Heissig et al., 2002); (Arai et al., 2004)).

It has been reported that following G-CSF-induced mobilization, several molecules, including thrombin, hyaluronan and fibrin accumulate in the blood ((Wysoczynski et al., 2005)), supporting a putative role for the hemostatic machinery in inducing HSPC recruitment to the periphery. These molecules were shown to prime the chemotactic responses of HSPCs toward SDF-1 by incorporating CXCR4 into lipid rafts and up-regulating MMP-2 and MMP-9 ((Wysoczynski et al., 2005)). In addition, the receptor for thrombin, PAR-1, is upregulated on G-CSF-mobilized human CD34+ HSPCs as compared to BM-resident CD34+ HSPCs ((Steidl et al., 2003)). Altogether, we hypothesize that the hemostatic fibrinolytic machinery is implicated in physiological egress and stress-induced mobilization of HSPCs, as shown by involvement of its different components, including plasminogen/plasmin, uPAR and possibly thrombin. Nevertheless, this new concept requires elaborative research to be better understood. We have discussed intrinsic and extrinsic molecular machineries in the induction of HSPC mobilization, however, HSPC recruitment does not depend only on the molecules involved (e.g. enzymes, chemokines and adhesion molecules), but also on interactions with other cellular players in the BM microenvironment, as discussed next.

8. The dynamics of the HSC niche and BM microenvironment during mobilization

Coupling of bone formation and bone degradation, carried out by MSPC-derived osteoblasts and monocyte-derived osteoclasts, respectively, is part of a complex process of bone remodeling. Noteworthy, osteoblasts and osteoclasts maintain bone equilibrium by acting in the endosteum in the vicinity of HSCs ((Kollet et al., 2007)). Thus, the endosteal stem cell niche is dynamically altered during bone remodeling, affecting HSC function and maintenance. Furthermore, accumulating evidence supports dynamic alteration of the HSC microenvironment upon stress-induced mobilization procedures. G-CSF or cyclophosphamide injections as part of a clinically-oriented HSC mobilization procedure lead to disappearance or altered morphology of bone-lining osteoblasts, resulting in their reduced function, which is associated with reduced transcription of SDF-1, SCF and VCAM-1 ((Semerad et al., 2005); (Christopher et al., 2009); (Katayama et al., 2006)–(Winkler et al., 2012); (Li et al., 2012)). Of interest, upon G-CSF/ cyclophosphamide administration, osteoblasts rapidly expand, promoting HSPC proliferation, prior to their apoptosis, which in turn enables loss of HSPC retention ((Mayack et al., 2008)). The importance of the BM stromal cells for the retention of HSPCs can be illustrated, for example, by the conditional deletion of the cell cycle regulator Retinoblastoma protein (Rb). Not only absence of Rb in the murine hematopoietic system, but also absence of Rb in the BM stroma alone is sufficient to increase the numbers of circulating HSPCs, in addition to a myeloproliferative-like disease and extramedullary hematopoiesis ((Walkley et al., 2007); (Daria et al., 2008)).

8.1. Involvement of osteoclasts

G-CSF administration causes robust appearance of active osteoclasts in human individuals and mice ((Takamatsu et al., 1998); (Watanabe et al., 2003); (Li et al., 2012)), which is associated with cleavage of SDF-1 protein in the endosteum and BM fluids ((Kollet et al., 2006); (Levesque et al., 2003); (Petit et al., 2002)). The relevance of osteoclast precursors to maintenance of the HSC niche was shown when they were seeded in vitro on osteoblast monolayer inducing osteoblast retraction ((Perez-Amodio et al., 2004)), temporarily altering the potential of confined areas of the endosteum to provide osteoblast-derived niche supportive signals in vivo. Immature osteoclast precursors are recruited to the blood circulation following S1P gradients and into the BM following SDF-1 gradients as part of the osteoclast differentiation pathway ((Ishii et al., 2009)–(Wright et al., 2005)). A transient increase in SDF-1 production following each G-CSF injection ((Petit et al., 2002)) may contribute to enhanced recruitment of osteoclast precursors and may eventually promote bone resorption. Accordingly, a robust increase in tartrate-resistant acid phosphatase (TRAP)-positive osteoclasts was observed in the endosteum in response to five daily administrations of SDF-1 in mice. This intensive activation appears to promote bone remodeling, affecting the endosteal niche. Indeed, we have demonstrated that mouse receptor activator of nuclear factor-κB ligand (RANKL)-stimulated osteoclasts are actively involved in physiological egress as well as in G-CSF-induced mobilization of HSPCs, in a CXCR4, MMP-9- and cathepsin K-dependent manner ((Kollet et al., 2006)). In parallel, key endosteal components, such as SDF-1, SCF, and osteopontin (OPN), are degraded in response to osteoclast activity, enabling HSPC detachment from the niche and their recruitment to the circulation ((Kollet et al., 2006); (Cho et al., 2010)). Our data is also supported by observations in BM biopsies obtained from human donors that underwent G-CSF treatment regimen \(Li et al., 2012)). A mobilization response to G-CSF was therefore abolished in female PTPε KO mice, in which osteoclasts are temporarily defective. In addition, osteoclast inhibition by treatment with the hormone calcitonin was able to reduce the effect of G-CSF and lipopolysaccharide (LPS) on HSPC recruitment to the PB ((Kollet et al., 2006)). Another example is given by CD45 KO mice, which manifest defective osteoclast activity. CD45 KO mice were found to poorly mobilize in response to sub-optimal G-CSF administration or in a response to RANKL stimulation ((Shivtiel et al., 2008)).

Interestingly, contrasting evidence demonstrates that inhibition of osteoclast activity actually does not affect or even increases HSPC mobilization in response to G-CSF ((Takamatsu et al., 1998); (Winkler et al., 2010)). Hence, Miyamoto and colleagues suggest that osteoclasts are dispensable for HSPC mobilization, bringing their involvement into a questionable debate ((Miyamoto et al., 2011)). It should be noted, however, that in this study, op/op mice, which have perturbed myeloid differentiation, including of osteoclasts, do not survive upon exposure to a sub-optimal dose of chemotherapy in contrast to surviving WT mice, indicating that hematopoiesis is severely impaired despite normal mobilization ((Miyamoto et al., 2011)). One possibility for this high sensitivity to chemotherapy is increased HSPC cycling as a result of osteoclast loss. Indeed, it was shown that osteoclast inhibition by bisphosphonates leads to increased HSC cycling together with reduced repopulation capacity of HSCs ((Lymperi et al., 2011)), suggesting that osteoclasts maintain the niche integrity that controls HSC quiescence. Human patients with congenital bone diseases or murine models that lack functional osteoclasts develop severe osteopetrosis, which is characterized with increased bone mass, dwarfism, deafness, blindness, strokes, frequent infections, and is also associated with extramedullary hematopoiesis and other hematological defects ((Dougall et al., 1999)–(Askmyr et al., 2008)). Notably, by recruitment of stromal precursors to sites of bone resorption as part of the bone remodeling cycle ((Wu et al., 2010)–(Tang et al., 2009)), osteoclasts also regulate bone formation. Of note, the recruited stromal precursors are the progeny of reticular MSPC that also form the HSC niche. Thus, we suggest that osteoclasts also participate in the initial formation and the ongoing dynamic maintenance of the HSC niche, which is required for HSC maintenance. In support of this claim, a recent study by Mansour and colleagues, performed in new-born oc/oc mice, shows that lack of osteoclasts leads to reduced HSC numbers in the BM, reduction in expression of genes required for HSC maintenance, increased numbers but defective MSPCs as well as impaired homing and repopulation of HSPCs ((Mansour et al., 2012)). It was also shown that osteoclast inhibition hampers the increase in MSPC numbers in the BM in response to G-CSF ((Brouard et al., 2010)).

Taken together, we suggest that prolonged inhibition of osteoclasts and more strikingly defective osteoclasts at birth leads to the formation of abnormal BM niches. As a result, HSC maintenance is impaired and hematopoiesis is imbalanced. However, despite the fact that all osteopetrotic models share hematological defects, there is a wide range of heterogeneity. For example, osteopetrotic op/op, oc/oc mice and CD45 KO mice harbor reduced numbers of BM HSPCs ((Shivtiel et al., 2008); (Wiktor-Jedrzejczak et al., 1982); (Mansour et al., 2012)), whereas other models, such as the mild osteopetrotic PTPε KO, have normal levels of HSPCs in the BM ((Kollet et al., 2006)). This observation also correlates with extramedullary hematopoiesis typical of the more severe osteopetrotic models. In healthy normal mice (and supposedly in healthy humans), the BM niche is intact, negatively regulating HSPC proliferation and motility via adhesion interactions. Upon stress or administration of G-CSF, activity of osteoclasts is part of the mechanism by which HSPC detach from their BM niches, become motile and mobilization is induced. Nevertheless, under circumstances of osteopetrosis, the BM niche integrity is lost, therefore HSPC mobilization capacity should be evaluated in a different light. Once again, due to heterogeneity in the causation of osteopetrosis, different models manifest different observations with regard to HSPC mobilization capacity. While op/op and RANKL KO mice easily mobilize in response to G-CSF ((Miyamoto et al., 2011)), female PTPε KO mice have reduced HSPC mobilization ((Kollet et al., 2006)), and CD45 KO mice mobilize in response to a full-dose of G-CSF, but less to a sub-optimal dose of G-CSF or to RANKL ((Shivtiel et al., 2008)). Thus, in some osteopetrotic models, functional osteoclasts may not be required anymore to mobilize the deregulated HSPCs or do not even play a role in their physiological egress. Higher levels of steady state circulating HSPCs in human patients and in some of the osteopetrotic murine models support our hypothesis ((Miyamoto et al., 2011); (Steward et al., 2005)). In conclusion, it is reasonable to assume that HSPC mobilization in response to G-CSF administration in some osteopetrotic mice (e.g. op/op mice) cannot be compared to healthy WT mice, as suggested by Miyamoto et al. Hence, the unique roles for bone-resorbing osteoclasts in the regulation of physiological egress and stress-induced recruitment and localization of primitive HSPCs in both health and disease should be re-evaluated in order to provide final solutions for this debate.

8.2. Involvement of monocytes/macrophages

Chow and colleagues found that depletion of mononuclear phagocytes in mice was sufficient to mobilize HSPCs, suggesting that BM macrophages promote retention of HSPCs in the BM ((Chow et al., 2011)). Since macrophages play a crucial role in osteoblast growth and survival, it has been proposed that their depletion mobilizes HSPCs by disruption of the osteoblastic niche ((Winkler et al., 2012); (Winkler et al., 2010)). By using a variety of approaches to abrogate monocytes and macrophages from the BM, it was shown that G-CSF-stimulated recruitment of HSPCs to the PB is in fact dependent on a direct activation of the monocyte lineage ((Winkler et al., 2010); (Chow et al., 2011); (Christopher et al., 2011)). Another study, which supports the important role of BM-resident macrophages in regulating the osteoblastic niche, utilized chimeric mice, expressing the G-CSF receptor only in CD68+ macrophages. Upon G-CSF administration, HSPC mobilization and SDF-1 downregulation in the BM have been completely restored in these mice ((Christopher et al., 2011)). Furthermore, supernatants from G-CSF-stimulated macrophages reduced SDF-1 production by BM stromal cells in vitro ((Cho et al., 2010)). BM-resident macrophages therefore may regulate SDF-1 production by BM osteoblasts and other stromal cells by generation of factors that have yet to be determined. Of interest, cholesterol efflux pathways within mouse BM-resident macrophages are necessary to mediate this function, as lack of cholesterol transporters in macrophages and dendritic cells leads to osteoblast suppression, elevated plasma G-CSF levels and reduction in SDF-1 production in the BM, including by Nestin-GFP+ MSPCs ((Westerterp et al., 2012)). As a result, these mice demonstrated increased numbers of circulating HSPCs and extramedullary hematopoiesis ((Westerterp et al., 2012)). Strikingly, diet-based hypercholesterolemia induces leukocytosis and enhances HSPC egress via imbalanced SDF-1/CXCR4 regulation, observed by elevated SDF-1 plasma levels, CXCR4 downregulation in the BM and CXCR4 upregulation in the PB ((Gomes et al., 2010)). The impact of cholesterol homeostasis as well as glucose/insulin homeostasis (see findings with regard to diabetes under “The SDF-1/CXCR4 pathway”) on HSPC egress raises the question how diet and metabolism in general regulate HSPC function in both direct and indirect (e.g. BM macrophages) manners. Intriguingly, we have recently demonstrated the existence of an additional type of BM-resident myeloid niche cells regulating maintenance of primitive murine HSPCs. These αSMA+ monocytes/macrophages, which are located near small blood sinuses, produce Prostaglandin E2 (PGE2) in a COX2-dependent manner, apparently act to protect the HSPC pool from exhaustion in steady state and upon stress by direct contact ((Ludin et al., 2012)). Altogether, BM monocytes/macrophages emerge as central players in driving HSPC retention probably via osteoblast maintenance and SDF-1/PGE2 production, however, other immune cells of the innate immunity system play additional roles, as discussed next.

9. Involvement of the innate immunity

It has been demonstrated that a few amino acids located at the N-terminus of SDF-1 that are crucial for the biological activity of this chemokine may be removed by MMP-2 or MMP-9 ((McQuibban et al., 2001)). This proteolytic processing of SDF-1 completely inhibits its chemotactic properties. Since then, several factors have been reported to sensitize the responsiveness of HSPCs to a SDF-1 gradient. These factors include elements of innate immunity, such as cleavage fragments of the complement cascade molecule C3 ((Reca et al., 2003)), cationic antimicrobial peptides, such as cathelicidin (LL-37) and β-defensins ((Lee et al., 2010)–(Lehrer et al., 2004)), and PGE2, a member of the eicosanoid family ((Goichberg et al., 2006)–(Hoggatt et al., 2009)). Several arms of the innate immunity system are shown to be involved in regulation of HSPC egress and mobilization, including the complement system and neutrophil activation, as described herein.

9.1. Activation of the complement cascade

An evolutionary ancient danger sensing pathway, termed the complement cascade (CC), becomes activated not only in response to inflammation, but also in the BM during conditioning for transplantation by irradiation or during mobilization by G-CSF ((Kim et al., 2012); (Ratajczak et al., 2012)). Immunocompromised mice with reduced CC activity thus exhibit poor mobilization capacity ((Reca et al., 2007)). The third component of the CC (C3), which is stimulated during CC activation by either the classical or the alternative pathways, has been suggested to mediate HSPC retention, as C3 KO mice or administration of C3a receptor antagonist enhance the mobilization response to G-CSF stimulations ((Ratajczak et al., 2004)). HSPCs isolated from C3 KO mice engrafted normally into irradiated WT mice, implying for a defect in the hematopoietic microenvironment of these mice rather than intrinsic defects in the C3 KO mice-derived HSPCs ((Ratajczak et al., 2004)). Interestingly, C3 cleavage fragments sensitize HSPC responsiveness to SDF-1 gradients ((Reca et al., 2003); (Ratajczak et al., 2006); (Honczarenko et al., 2005)). The CC might also be activated directly at the fifth component of the CC (C5) level by coagulation-associated proteasesor by proteolytic proteases that are secreted from granulocytes upon their stimulation with mobilizing agents, including both G-CSF and AMD3100 ((Ratajczak et al., 2012); (Lee et al., 2009); (Lee et al., 2010)). It was already discussed that while G-CSF induces mobilization of HSPCs, several molecules, including thrombin, accumulate in the blood ((Wysoczynski et al., 2005)). The coagulation and the fibrinolytic factors, thrombin and plasmin, respectively, were shown to cleave C5 and C3, resulting in the generation of C5a and C3a ((Amara et al., 2010)). Additionally, the plasma levels of C5 cleavage fragments correlate with clinical mobilization efficiency and exposure to these fragments reduce chemotaxis towards SDF-1 ((Jalili et al., 2010)). In summary, C3 cleavage fragments increase retention of HSPCs in BM, while those of C5 cleavage enhance their egress into PB. It is evident by studies performed in C3 and C5 deficient mice, which revealed that C3 deficient mice are easy mobilizers ((Ratajczak et al., 2004)), whereas C5 deficient mice are poor mobilizers ((Lee et al., 2009)). It is yet to reveal how precisely the stress-activated CC triggers signaling cascades that potentiate HSPC motility as part of their recruitment to the PB.

9.2. Bioactive lipids-induced mobilization

The importance of SDF-1 levels in the BM is well established, however, several reports indicate that plasma SDF-1 levels do not correlate with G-CSF-induced mobilization efficiency in patients ((Cecyn et al., 2009); (Kozuka et al., 2003)). Other potential chemoattractants, responsible for egress of HSPCs into the PB, include heat-resistant bioactive lipids, in particular S1P that was previously shown to induce by itself chemoattraction of human and murine HSPCs ((Ratajczak et al., 2010)–(Ryser et al., 2008)). S1P is a bioactive lipid implicated in cell migration, survival, proliferation, angiogenesis as well as immune and allergic responses ((Alvarez et al., 2007)). Both human and murine HSPCs have been shown to express functional S1P receptors, which also cross-talk with SDF-1/CXCR4 signaling, affecting migration, adhesion, homing, mobilization, development and engraftment capacities ((Massberg et al., 2007); (Golan et al., 2012); (Kimura et al., 2004); (Walter et al., 2007)). Interestingly, S1P plasma concentrations increase in response to CC activation due to interaction of the membrane attack complex (MAC) with erythrocytes, the major reservoir of S1P in the body. Therefore, it is proposed that S1P is a crucial chemoattractant for BM-residing HSPCs upon CC activation, enabling proper recruitment of HSPCs to the circulation ((Ratajczak et al., 2010)). Accordingly, S1P concentrations in the plasma were increased following both G-CSF and AMD3100 treatments in mice as well as expression of its receptor S1P1 on HSPCs ((Golan et al., 2012); (Ratajczak et al., 2010)). Utilizing mice with reduced S1P production, mice that lack S1P1 or pre-treated with S1P1 inhibitor, we have recently shown a reduced capacity to mobilize upon G-CSF or AMD3100 treatments ((Golan et al., 2012)). Our results with regard to the involvement of S1P in AMD3100-induced mobilization of HSPCs are supported by others ((Ratajczak et al., 2010); (Juarez et al., 2012)). Furthermore, S1P was shown to induce SDF-1 secretion from Nestin-GFP+ MSPCs, followed by SDF-1 release from the BM to the circulation, adding another regulatory aspect for HSPC mobilization ((Golan et al., 2012)). As opposed to the pro-inflammatory S1P, PGE2 in fact prevents SDF-1 secretion ((Ludin et al., 2012) and unpublished data), strengthening its anti-inflammatory role, however, the role of PGE2 in HSPC egress is yet to be determined. Ceramide-1 phosphate (C1P) is another bioactive lipid derivative that was previously identified as a chemoattractant for mouse monocytes ((Granado et al., 2009)). Activation of CC correlated with an increase in the BM levels of both S1P and C1P ((Kim et al., 2012)). Interestingly, while S1P levels increase in PB mostly during mobilization, the C1P concentration in the BM fluids increases upon myeloablative conditioning for transplantation. Based on these findings, a new paradigm was proposed, in which the S1P:C1P ratio plays an important role in mobilization and homing of HSPCs. While S1P is a major chemoattractant that directs egress of HSPCs from BM to PB, C1P together with SDF-1 creates a homing gradient for circulating HSPCs (reviewed in ((Ratajczak et al., 2012))). Not only sphingolipids play a role in HSPC mobilization, as there a few indications for involvement of other bioactive lipids - endocannabinoids, which are derivatives of arachidonic acid. Endocannabinoids, synthesized in various tissues upon demand, have emerged as important lipid mediators that regulate central and peripheral neural functions as well as immune responses ((Tanasescu et al., 2010); (Jean-Gilles et al., 2010)). Endocannabinoids and exogenous cannabinoids treatments (i.e. psychotic drugs) are known to act also on the function of immature hematopoietic cells, including proliferation ((Valk et al., 1997); (Valk et al., 1998)) and migration ((Mohle et al., 2001); (Patinkin et al., 2008)). Notably, cannabinoid agonists rapidly mobilize and synergize with G-CSF stimulations ((Hoggatt et al., 2010); (Jiang et al., 2011)), suggesting involvement of another set of bioactive lipids with yet un-deciphered mechanisms. Altogether, recent data point at additional chemoattractive compounds, the bioactive lipids (e.g. S1P and endocannabinoids), that together with the SDF-1/CXCR4 axis mediate recruitment of HSPCs from the BM to the circulation, which brings about open questions to the field.

9.3. Involvement of neutrophils and ROS signaling

Neutrophils (the vast majority of granulocytes in the body) are essential component of the innate immune system, as they are the first responders to pathogens penetration (reviewed by ((Day et al., 2012))). G-CSF is important in driving granulopoiesis, as mice lacking G-CSF or its receptor, display chronic severe neutropenia ((Lieschke et al., 1994); (Liu et al., 1996)). G-CSF treatment was shown to induce a robust expansion of BM neutrophils and they are the first cells to egress from the BM during mobilization ((Day et al., 2012)). Furthermore, chimeric mice transplanted with G-CSF receptor deficient BM cells show impaired G-CSF-induced HSPC mobilization, despite having normal HSPC numbers ((Liu et al., 2000)). Mice deficient for G-CSF receptor also display inability to mobilize in response to IL-8 or cyclophosphamide ((Liu et al., 1997)). Of note, chemokines, such as IL-8 or GROβ, that strongly activate and chemoattract neutrophils, also induce HSPC mobilization ((King et al., 2001)–(Pruijt et al., 2002)). The major mediators of neutrophil driving force in HSPC mobilization are proteolytic enzymes, which are released by activated neutrophils into the BM microenvironment and periphery. These proteolytic enzymes interfere with the SDF-1/CXCR4, VLA-4/VCAM-1 and SCF/c-Kit retention signals that preserve HSPCs in their niches ((Levesque et al., 2003); (Levesque et al., 2003); (Levesque et al., 2002)), enabling subsequent recruitment from the BM to the PB (more on neutrophil-derived proteolytic enzymes is described in the “proteolytic activity” section). It is essential to note that the role of neutrophils in the stress-induced recruitment of murine HSPCs is also manifested following activation of the CC. CC-induced granulocytosis is associated with the release of the bioactive lipids S1P and C1P that are implicated in HSPC mobilization (discussed under “bioactive lipids-induced mobilization and reviewed by ((Ratajczak et al., 2012))). In addition, C5 cleavage fragments orchestrate the mobilization process directly by activating and chemoattracting neutrophils ((Lee et al., 2009); (Jalili et al., 2010)). Of interest, neutrophils permeabilize the sinusoid endothelial barrier in the BM as was depicted by transmission electron microscopy studies ((Lee et al., 2009)). Indeed, disruption of the BM endothelial barrier is prominent during repetitive G-CSF stimulations ((Szumilas et al., 2005)). The requirement of neutrophils for HSPC mobilization induced by G-CSF was supported by a recent study showing that G-CSF induces expansion of neutrophils in the BM of mice together with induced apoptosis of MSPCs and osteoblasts through increased reactive oxygen species (ROS) production and reduced expression of factors that are responsible for HSPC retention in the BM, including SDF-1, SCF and VCAM-1 ((Singh et al., 2012)). Administration of neutralizing antibodies that deplete activated neutrophils in mice led to attenuation of the G-CSF mobilization effects ((Singh et al., 2012)). ROS generation is pivotal to fight against pathogens and is involved in apoptotic processes, however, it serves also as a common signaling mediator. Except for ROS generation in activated neutrophils, ROS signaling is a key cell-intrinsic mechanism during HSPC recruitment to the periphery. We have demonstrated that inhibition of ROS generation by the anti-oxidant N-Acetyl Cysteine (NAC) could preferentially attenuate G-CSF- and AMD3100-induced mobilization of murine HSPCs ((Dar et al., 2011); (Tesio et al., 2011)), suggesting that ROS signaling is involved in physiological HSPC motility and egress. In fact, the scenario is more complex, as it was found that granulocytes, activated by the G-CSF stimulations, release hepatocyte growth factor (HGF), which in turn binds to its receptor c-Met on the HSPC themselves, triggering mTOR/ROS signaling ((Tesio et al., 2011)). It is therefore not surprising that direct administration to mice of HGF or blocking c-Met also potentiates or inhibits HSPC mobilization, respectively. Strikingly, the S1P/S1P1 axis, as noted earlier, mediates mobilization via mTOR/ROS signaling as well ((Golan et al., 2012)). This study illuminates ROS production levels following S1P elevation in two BM compartments: in primitive HSPCs, where ROS motivate their migratory potential, and in the stromal compartment, where ROS enhance SDF-1 secretion ((Golan et al., 2012)). Of note, inhibition of ROS by NAC not only reduces AMD3100-induced mobilization of HSPCs, but also reduces the induction of SDF-1 release ((Dar et al., 2011)). These studies identified a cross talk between S1P/S1P1 and SDF-1/CXCR4 via ROS signaling, which is essential for HSPC egress and mobilization ((Dar et al., 2011); (Golan et al., 2012); (Tesio et al., 2011)). Of note, increased mTOR signaling due to conditional absence of its negative regulator TSC1 in mice leads to enhanced HSPC egress in addition to other hematopoietic defects, supporting the involvement of mTOR/ROS signaling in HSPC mobilization ((Gan et al., 2008)). Collectively, results taken from different studies support the claim that neutrophils are key elements in the multi-angled induction of HSPC mobilization, as shown by release of proteolytic enzymes, suppression of MSPCs/osteoblasts, involvement in the mechanism of CC activation, ROS generation and activity of bioactive lipids. Apart from the immune system, a novel and surprising regulator of HSPC mobilization and function in general has emerged in recent years, which is the central and peripheral nervous system as discussed below.

10. The nervous system